1.

James Michener’s novels are like Gideon Bibles: they pop up everywhere and no one seems to read them from cover to cover. I myself hadn’t read one until very recently, which is remarkable, because I seem to have been born knowing the author’s name. I doubt there was a time in my life when I could not tell you the title of at least one Michener novel; I even remember the first time I almost finished a page of one: I was in my 20s, staying at a cheap hotel in Kunming in the mid-90s. There wasn’t much of a library in the lobby, but there was plenty of Michener. I took down a tattered copy of Hawaii (or was it Poland?) from the flimsy wicker bookstand, but the words started swimming before I could finish the first page.

James Michener’s novels are like Gideon Bibles: they pop up everywhere and no one seems to read them from cover to cover. I myself hadn’t read one until very recently, which is remarkable, because I seem to have been born knowing the author’s name. I doubt there was a time in my life when I could not tell you the title of at least one Michener novel; I even remember the first time I almost finished a page of one: I was in my 20s, staying at a cheap hotel in Kunming in the mid-90s. There wasn’t much of a library in the lobby, but there was plenty of Michener. I took down a tattered copy of Hawaii (or was it Poland?) from the flimsy wicker bookstand, but the words started swimming before I could finish the first page.

Back then I gave myself over to long novels only if I believed they would change my life (Tolstoy) or alter my mind (Pynchon). When it came to serious investments of reading time, I preferred no-doubt-about-it recommendations over my own theoretical ability to take serious pleasure in unintended masterpieces, like a Roland Barthes wannabe (I might have been able to decode a cereal box as a lyric poem, but I wasn’t willing to read the entire Yellow Pages as though it were an epic). No one ever told me to read Michener on account of its literary merit either, and on the few other occasions I tried to read him up until last year — in airports, barber shops, even a dentist’s office — I felt like I was wasting time on something with questionable payoff, even as a form of escapism—precious time I could be spending on the Koran or re-reading Proust.

2.

During a recent visit to Greeley, Colorado — the town on which Michener based Centennial in his novel of the same name — I told my uncle, who has lived there his entire life, about my new determination to read Michener. Re: Centennial, his response was swift: “Skip all the bullshit about evolution and research.” I appreciated the frankness, but didn’t tell him that I actually liked the bullshit about how the Rocky Mountains had replaced a much older range.

During a recent visit to Greeley, Colorado — the town on which Michener based Centennial in his novel of the same name — I told my uncle, who has lived there his entire life, about my new determination to read Michener. Re: Centennial, his response was swift: “Skip all the bullshit about evolution and research.” I appreciated the frankness, but didn’t tell him that I actually liked the bullshit about how the Rocky Mountains had replaced a much older range.

The Rockies are therefore very young and should never be thought of as ancient. They are still in the process of building and eroding, and no one today can calculate what they will look like ten million years from now. They have the extravagant beauty of youth, the allure of adolescence, and they are mountains to be loved.

Nor did I mention my fondness for the novel’s narrative frame, in which a high-profile magazine in Manhattan pays a celebrated history professor a large sum of money to conduct anonymous research for a feature article on the Platte River.

I liked the frame because it doubled as a commentary on fiction writing, Michener-style. It goes like this: the happy learned scholar wows the savvy publishers with maverick story-telling. They accept his reports without question. These reports, which comprise the chapters of the novel, demonstrate the professor’s, and Michener’s, ability to formulate the minutia of local history into sweeping narratives about the injustices (and occasional justices) committed by settlers and the U.S. government against native tribes along the front range of the Rockies. In his instructions to the editors at the end of each chapter, the professor doubles down on his fine-grained knowledge, which is all a part of his mission to get things right.

Please, please make your artist exercise restraint in illustrating this section. I have studied forty-seven photographs of groups of cowboys in the years 1867-68-69, and not one appears in chaps, tapaderos, or exaggerated hat. All wear working clothes, plus high-heeled boots, and bandanna.

Another cliché narrowly avoided, seems to be the message. I imagine the well-meaning fictional editors back in New York cherishing the preemptive correction about cowboy apparel as though it were a nugget of truth—dug up by a man for whom minor details mean everything. For they are in the presence of the real deal, the irrepressible teacher.

Michener did in fact have a sense of how such fictional editors in the New York publishing industry might have dealt with this narrator. Prior to volunteering for the Navy in World War II, he worked as a textbook editor at Macmillan. Perhaps like the bold narrator in Centennial, he himself worked the system of trade publishing without sacrificing his social and intellectual principles.

3.

My uncle went on to warn me about specific historical inaccuracies in Centennial. He knew his stuff. While a reporter for the Greeley-Tribune, he had written a column about the area’s local history and, in the late 70s, even worked as an extra in NBC’s made-for-TV-movie adaptation of the novel. The non-fiction is better, he told me; read Report of the County Chairman. I haven’t yet read Michener’s account of traveling with JFK on the presidential campaign trail, but my uncle’s warning had the effect of making me study the novels I was reading more seriously: I couldn’t just ride along without wishing to corroborate what I was reading. I wanted to know what was made up, and why.

Michener does make things up, and I don’t always know enough about the places described in his stories to judge when he is being cavalier, or misleading; but this no longer matters much to me. His novels became worth my while when I considered their author not an authority with the final word — on Colorado, Afghanistan, or the Caribbean — but a thoughtful yet flawed university lecturer, whose approach to sweeping historical tales is capacious enough to allow and encourage me to think things through on my own. (And for that, they need to be long.) Now I think of Michener’s novels as efficiently designed college courses in the humanities.

And who knows? Maybe big novels written expressly to educate and engage the imagination can already accomplish what the coming onslaught of online courses will attempt to do. Maybe we need to turn to historical novels and other yet-to-be created expository fiction composed by gifted writers, not virtual classrooms built by techie educators. Fiction can teach without being didactic, but maybe this comes easier to authors who’ve been on the planet for more than two or three decades.

4.

Michener wrote plenty before Tales of the South Pacific, his debut novel at age 40, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1948. At the University of Northern Colorado in the 1930s he wrote articles that only a social scientist with Keats running around in his head could write. Co-ed sex education was one of his subjects, but so was using music in the social sciences. The quirky title of one article he published, “Bach and Sugar Beets,” argued that music could open up rural students to new ideas about agriculture. It sounds like the kind of catchy course title now on offer at Harvard, where, incidentally, Michener taught and pursued a Ph.D. in history after studying at the University of St. Andrews and majoring in the multidisciplinary Honors Program at Swarthmore. But before Tales of the South Pacific, he had published only one piece of fiction, a short story called, “Who is Virgil T. Fry?” More of a personal manifesto than anything else, the story features a high school teacher whose messy imagination freaks out the other teachers and the principal, but wins the hearts and minds of his students. The teacher gets canned for being too good.

Michener wrote plenty before Tales of the South Pacific, his debut novel at age 40, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1948. At the University of Northern Colorado in the 1930s he wrote articles that only a social scientist with Keats running around in his head could write. Co-ed sex education was one of his subjects, but so was using music in the social sciences. The quirky title of one article he published, “Bach and Sugar Beets,” argued that music could open up rural students to new ideas about agriculture. It sounds like the kind of catchy course title now on offer at Harvard, where, incidentally, Michener taught and pursued a Ph.D. in history after studying at the University of St. Andrews and majoring in the multidisciplinary Honors Program at Swarthmore. But before Tales of the South Pacific, he had published only one piece of fiction, a short story called, “Who is Virgil T. Fry?” More of a personal manifesto than anything else, the story features a high school teacher whose messy imagination freaks out the other teachers and the principal, but wins the hearts and minds of his students. The teacher gets canned for being too good.

An assessment of Michener’s growth as a fiction writer before Tales of the South Pacific depends on how you define fiction. As a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, he wrote plenty of narratives about what he saw and heard. That was part of his job as jack-of-all trades intelligence messenger. But everything changed when an admiral ordered him to Bora Bora to make a report on why the enlisted men on the island refused to go home. A color photo of the island’s limpid waters and coconut palms is explanation enough for me, but Michener conducted extensive interviews and dutifully typed out the kind of sprawling explanation found in his subsequent novels. In his investigation, he went well beyond the call of duty — for incipient writerly reasons — and saved for himself the beaches and coconuts, not to mention the proud Tonkinese women and decadent French plantation owners. These things would figure into Tales of the South Pacific, which he mailed to Knopf in a waterproof package several months later.

Michener’s laurels might never have sprouted from this military reporting had it not been for two life-changing events. The first was an impromptu forgery: at the very end of his long awful voyage from San Francisco to the South Pacific, he and another rookie lieutenant snuck into the captain’s quarters and found documents detailing their next assignments. The other lieutenant, a stockbroker in civilian life, knew Michener to be a man in love with travel and so brazenly fabricated, right then and there, a document authorizing him to travel throughout the Pacific’s military zones on vague but empowering “tours of inspection.” I get a whiff of tall tale-telling here in Michener’s memoir, but not because I think he made up the story. I’m just not so sure he didn’t forge the document himself.

The other life-changing event started to unfold when a plane taking Michener to New Caledonia had trouble landing. On the third attempt in worsening visibility, the pilot narrowly succeeded with little fuel left in the tank. The miracle rattled Michener. Unable to sleep that night, he wandered around in a tense stupor until he found himself back on the airstrip. He walked up and down for a long time, and, after growing calm, his thoughts lifted him into those bright skies of self-reckoning. What was he to do with the rest of his life? Did he really want to return to his job as an editor of textbooks and a life of professional competence? He silenced these questions by swearing an oath: “I’m going to live the rest of my life as if I were a great man.” He had no idea what he meant.

5.

I’ve learned to expect the grand outburst from Michener. They come like little fountains of emotion in long stretches of exposition, and so they’re welcome, like a stern teacher’s occasional joke. In Caravans, his novel about Afghanistan in the 1950s, such eruptive oases recall Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky but without the sense of foreboding that makes everything seem so desperate.

I’ve learned to expect the grand outburst from Michener. They come like little fountains of emotion in long stretches of exposition, and so they’re welcome, like a stern teacher’s occasional joke. In Caravans, his novel about Afghanistan in the 1950s, such eruptive oases recall Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky but without the sense of foreboding that makes everything seem so desperate.

We went into the night and for the first time in my life I saw the stars hanging low over the desert, for the atmosphere above us contained no moisture, no dust, no impediment of any kind. It was probably the cleanest air man knows and it displayed the stars as no other could. Not even at Quala Bist, which stood by the river, had air been so pure. The stars seemed enormous.

As he rhapsodizes in superlatives, the narrator, a novice U.S. diplomat, is following the trail of a proto-hippie American woman who has left her American-educated, Afghani husband for a noble Bedouin chief. But Caravans is also a page-turning fable about the monumental proportions of freedom, American-style. Every character in Caravans wants to be great, and Michener is generous enough to let their successes and failures stand without sizing up the moral legitimacy of the motivating desire.

I doubt Michener ever settled on a definition of greatness for himself or his characters. Even in his own airstrip epiphany, it’s clear he wasn’t going after greatness for its own sake. That would be too easy. What he really got into was the creative thrill of faking it ‘til he made it. A restless man giddy with the excitement of making his life count, he walked away from the airstrip with a heightened awareness of everything and everyone around him. The typewriter in his Quonset hut turned into the ballast he needed to sort things out. And the ballast felt particularly good when an enlistee who passed the time making necklaces out of seashells read Michener’s stuff and told him it wasn’t bad, not bad at all. A reporter still, Michener had a new beat: the fictional version of his life. And so it remained until his 80s when he wrote his autobiography, appropriately titled The World Is My Home.

I doubt Michener ever settled on a definition of greatness for himself or his characters. Even in his own airstrip epiphany, it’s clear he wasn’t going after greatness for its own sake. That would be too easy. What he really got into was the creative thrill of faking it ‘til he made it. A restless man giddy with the excitement of making his life count, he walked away from the airstrip with a heightened awareness of everything and everyone around him. The typewriter in his Quonset hut turned into the ballast he needed to sort things out. And the ballast felt particularly good when an enlistee who passed the time making necklaces out of seashells read Michener’s stuff and told him it wasn’t bad, not bad at all. A reporter still, Michener had a new beat: the fictional version of his life. And so it remained until his 80s when he wrote his autobiography, appropriately titled The World Is My Home.

6.

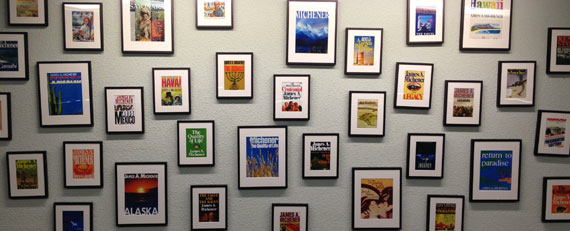

Not bad at all. That’s what I thought when I went to the Michener Library at the University of Northern Colorado and stood in front of a wall displaying the bright covers of 42 books by the author after passing a case displaying his dentures. Such prolific output is inspiring if only as a monument to persistence (even after factoring in the teams of supporting researchers he employed once his books became bestsellers). Only a Michenerologist would be able to tell you something specific about each of those books, not to mention the many others he published. Altogether he wrote 26 novels, and I’m certainly no such specialist, but from what I’ve read so far I can recommend Michener to the insomniac fan of marathon historical fiction who doesn’t mind being told and not shown. Michener is an unrepentant teller with little appetite for showmanship. Especially in his early fiction, he has the tendency to lead by the nose, like a zealous and patronizing adjunct. Take for example the way he drops two characters into Tales of the South Pacific with the grand blandness of abstraction:

Hers was the heart-hunger that has sent people of all ages in search of new thoughts and deeper perceptions. Yet at the end of a year in Navy life Nellie had found only one person who shared her longing for ideas and experience. It was Dinah Culbert. She and Dinah had a lust for sensations, ideas, and the web of experience. She and Dinah were realists, but of that high order which includes symbolism and some things just beyond the reach of pure intelligence.

I dig these gals, but only on faith because I have no idea which specific colors stripe their potentially bright rainbows. And so I forget them. But such narrative explanation can be comforting when it helps keep you on track of the many subplots he lays out like a compulsive scholar whose curiosity has broken loose.

Reading Michener and liking it in the 21st century requires tolerance for the ambivalence it inspires. I may have cringed at his attempts to capture Japanese-accented English in Sayonara (“You be good man not tell anyone you love Hana-ogi. She make very dangerous come Osaka for you”), but read on, because I recognized that he wanted to teach me what he knew about American-occupied Japan. I also rolled my eyes at his fetishistic idealizations of Japanese women in the same novel:

Reading Michener and liking it in the 21st century requires tolerance for the ambivalence it inspires. I may have cringed at his attempts to capture Japanese-accented English in Sayonara (“You be good man not tell anyone you love Hana-ogi. She make very dangerous come Osaka for you”), but read on, because I recognized that he wanted to teach me what he knew about American-occupied Japan. I also rolled my eyes at his fetishistic idealizations of Japanese women in the same novel:

For women in love there could be no garment more entrancing than the kimono. As I watched Hana-ogi, I realized that in the future, when even the memory of our occupation has grown dim, a quarter of a million American men will love all women more for having tenderly watched some golden-skinned girl fold herself into the shimmering beauty of a kimono. In memory of her feminine grace, all women will forever seem more feminine.

But I tolerated this objectifying megalo-kimono-philia long enough to realize the larger story was a surprisingly nuanced meditation on the vicissitudes of mixed-race relationships in the fraught political climate of military occupation, in this case between a Japanese woman and an American man. The lovers risk rejection from their respective communities on account of racial prejudice — the woman from her theatrical troupe in Takarazuka that prohibits dating any man and especially an American; and the American lieutenant from the elite military he was born to marry into. In Tales of the South Pacific, Centennial, and Caravans too, Michener’s mission was to shine a light on the changing forms of racism; but in the case of Sayonara, the sheer cheesiness of the romance and the touches of what some readers will call Orientalism will no doubt cloud that mission, which is something that the overblown film adaptations of the novels only make worse.

So maybe Michener was indeed a flawed teacher, his oeuvre a dense curriculum of introductory courses about the Jews, Alaska, and even outer space. His attempt to present all sides of the story in an evenhanded way is noble and naïve, certainly old-school professorial and occasionally pedantic. His prose is more sugar beet than Bach, more social scientist than artist, but like any good teacher, it inspires you to take a seat in the middle of the world like it’s your own personal classroom. That’s why I plan to read more Michener. Some may consider him a mass-market hack, but he’s also an untiring muse who doesn’t care if I nod off to sleep during lecture, just as long as my hand shoots up with questions at the end of class.

Image via the author