In 1929, George Orwell had a nightmarish stay in a Paris hospital. He described the experience in his essay, “How the Poor Die.” “This business of people just dying like animals, for instance, with nobody standing by, nobody interested, the death not even noticed till the morning — this happened more than once. You certainly would not see that in England, and still less would you see a corpse left exposed to the view of other patients.” Yet, as he pointed out, it had not been so long ago that such horrors existed in his native England. The inhumanity of that hospital pointed to the primitive conditions by which the English had treated their sick throughout the 19th century. By 1929, such memories existed only in England’s subconscious. And so he had to travel abroad to find a place where the subconscious was still conscious.

In 1929, George Orwell had a nightmarish stay in a Paris hospital. He described the experience in his essay, “How the Poor Die.” “This business of people just dying like animals, for instance, with nobody standing by, nobody interested, the death not even noticed till the morning — this happened more than once. You certainly would not see that in England, and still less would you see a corpse left exposed to the view of other patients.” Yet, as he pointed out, it had not been so long ago that such horrors existed in his native England. The inhumanity of that hospital pointed to the primitive conditions by which the English had treated their sick throughout the 19th century. By 1929, such memories existed only in England’s subconscious. And so he had to travel abroad to find a place where the subconscious was still conscious.

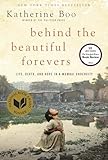

Katherine Boo has made a career chronicling poverty among Americans of different phenotypes, the victims of society’s misplaced priorities. But she is a humanist not a polemicist. For the last decade, her profiles of America’s underclass in The New Yorker have described the intimate lives of refugees from Hurricane Katrina, a Washington, D.C., mother whose life is changed by welfare reform and single black women in Oklahoma who are encouraged by the government to participate in the “marriage cure.” But in her first book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, which has just been nominated for a National Book Award, Boo tells the story of Annawadi, a slum in Mumbai populated by figures brutalized by the worst forms of urban poverty. Like Orwell, she describes an environment with a gruesome character that can only be found abroad. The aura of that character, however, still permeates the world of America’s underclass.

Annawadi is a slum beset by its own hierarchies and politics. Boo, who employed the assistance of three translators — Mrinmayee Ranade, Kavita Mishra, and Unnati Tripathi — chronicles the story of one of its inhabitants, Abdul Husain, a young scavenger who gets entangled with his family in a terrifying legal ordeal. Boo’s book is written with a fine melancholic prose. A friend of mine underlined one particular paragraph as the subject of his awe:

At the orphanage, when rich white women visited, Sunil had refused to beg for rupees. Instead he’d harbored the idea that one of the women might single him out, reward his dignified restraint. For years, he had waited for this discriminating visitor to meet his eye; he planned to introduce himself as ‘Sunny,’ a name a foreigner might like. Eventually, he’d come to realize the improbability of his hope, and his general indistinction in the mass of need. But by then, the habit of not asking anyone for anything had become a part of who he was.

I spoke with Boo by phone in February shortly after the book was launched. There were a few technical glitches with the iPhone application I used to record us and so the following is a slightly pared-down version of a 45-minute conversation.

The Millions: You don’t really allow us to exit the worldview of the citizens of Annawadi, except for — every now and then — a paragraph or two that describes the greater forces of the world economic system.

Katherine Boo: Right. When the book begins in January 2008, one of the kids has broken the invisible barrier between the slum world and the rich world. And he is describing the luxury around the slum. The slum is right by luxury hotels. That’s just an example of something I’m trying to do. I didn’t want to break away and say, “Here are the hotels. This is what it looks like.” It was a moment where this 15-year-old kid was explaining to the other kids what it’s like to be in that world. And one of the things he said that was really striking was, “You stepped on a carpet and you sunk right down.” And that made such an impression on him. And if I were in a hotel that would never have occurred to me, but now every time I’m in a place with a plush carpet I think about it.

So it was important to me to keep the perspective as much as possible [of] what the people in the slum saw and understood or were impressed and moved or weirded out by in this wealthier part of the city. Or the things that Rahul was talking about, how weird rich people get when they get drunk. And you notice when he’s talking he’s talking about the fine cloth on his suit, the stripe on his suit. To me it’s much more interesting what he sees than what I would have gone in and written about.

TM: There’s one detail that struck me early on…Abdul [is] scavenging in the garbage and you describe that when he sees a Barbie doll, he turns it around so that [its frontal nudity] faces away from him.

KB: From the beginning, I’m watching him work and I’m watching the way that he works. The first description Sunil, the young scavenger, had of Abdul was “he keeps his head down day and night.” So he’s physically hunched, sorting this garbage, supporting a family of 11. And what’s so striking is he’s not just giving them a subsistence living; by sorting garbage, he has given them one of the most hopeful prospects of anyone sorting in the slum.

So you’re watching this happen. And you’re seeing him doing this [with the Barbie doll]. And you see him do this once. And then you see him do this a second time. This is maybe three weeks later. And you’re like “This is what he’s doing.” My friend Anne Hull who is a brilliant investigative journalist — she did the work on Walter Reed for The Washington Post — talks about the earned fact. So when you’ve seen [something] enough times, you know you’re not imposing, you’re not writing it for literary effect. This is the way [Abdul] reacts to the world. And there are other examples of that which [I] don’t put into the book. When you find that one example in the course of your reporting, then you can write about a person with more conviction…I think the reader might sense that.

TM: So did you directly ask him why he [turns the Barbie doll] away from him?

KB: Yes. Once I saw him doing it. I never would have thought it. And then you say, “Why did you do that? I just saw you do that the other day.” And then you get to talking about it.

Abdul talks about how “a good life is the train that hasn’t hit you and the malaria you haven’t caught.” And where he’s sorting his garbage is across the street [from] the guy who the train hit. And two huts down is the guy with malaria or dengue. And he talked about alertness, that he wasn’t smart but he was alert. That began the conversation in which he could explain what he was feeling. And then I could put it in of my own words. But I think it absolutely captures what his worldview is.

TM: Were there any moments where people felt you were crossing the line in asking them a question like that. He may not have felt you were crossing the line with a question like that. But there may have been some other questions.

KB: Well no, not on that particular issue. But [it did happen] in the course of fact-checking, and in the course of re-interviewing people to go over and over, to understand what happened in certain pivotal moments in the book, for instance the self-immolation of Fatima. When I was interviewing people two years after that happened, many people thought it was inauspicious to revisit such painful memories. They just didn’t find it useful in their ability to go on everyday. And there was a part of the book where I talk about Zehrunisa, how she’s an expert curser and she cursed me straight across the maidan, “I can’t relive this again.” And we tried and tried. But she said, “I can’t go through this again.”

TM: How do you deal with grieving Fatima’s death or Meena’s death? Did you feel you needed to take a step back to grieve privately?

KB: Yes. And the deaths that you read about in this book are not the only deaths that upset me immensely. This book is not the chronicle of every awful thing that ever happened there. Many other things happened there that affected me immensely, but I’ll just give you an example after Fatima’s death. I have this amazing friend who is an investigative journalist and is now a novelist, Lorraine Adams. And one day she just materialized on my doorstep and made me talk about [the death]. She came down from New York. She made me talk about why I felt I could never make anyone care about these people the way I cared about them. She made me realize I just had to keep on doing my reporting. I couldn’t just sit there on my couch. Obviously, it was late for those children, but if I could investigate and document a little better, maybe some attention would be paid.

TM How long was this period for?

KB: At some point it was just one tragedy after another and I had to, as you say, grieve privately. Three chapters were written in two years. When you write about the death of this little girl…The first draft is written through tears. And you try to come back and get your composure. But obviously, there were moments in this book that were devastating to me.

TM: You note you’re not quite as interested about the differences between American and Indian poverty. But you are fascinated by the similarities. How would you define those similarities exactly?

KB: There are obviously differences. In lower-income communities in Mumbai, fewer people have guns, for instance. So there’s less violent crime. By contrast, police stations in Mumbai are more dangerous than the ones in American inner cities — and let me underline at times that American inner-city police stations are not beautiful places to be. But there are poor people [in India] who are victimized by violent crime [who] would never dream of going to the police station because it would just be another round of victimization. And I describe the day that people are saying there is a death in the road. And no one wants to go to the police station and tell them the guy is there. [The guy’s] a scavenger. He’s stigmatized anyway. But no one wants to risk their own liberty and their own well-being to tell the police, which is why everyone walks away while this man is dying in the road. And I think in the American inner city that just wouldn’t happen. It doesn’t mean that everyone wouldn’t immediately call the police. People do call 911. People who are victimized feel in the main that there is some authority that they can turn to.

TM: But you say that the similarities between poor people in the two countries are that there is a desire for one’s children to be less poor [and] that there is a desire for some form of social mobility. And there’s an amazing desire among the wealthy to blame the poor for their own condition and for the poor to blame themselves. For you those seem to be constants.

KB: Yes. One of the things you have in low-income communities, whether it’s in South Texas or in the slums of Louisiana or South Boston or Washington and in Mumbai and London, where I’m basically spending a lot of time because my husband just got a job there, is that fewer and fewer people have permanent work. More people are improvising. Capital is going all over the planet. And it’s restless. And so there’s more of a sense of volatility, of economic volatility. There was this kid Norberto, a high school student I profiled for The New Yorker awhile ago, who worked in itinerant construction. And he said, “I hate this phrase ‘I can’t get ahead.’ My family gets ahead all the time and then the carburetor breaks and we slip back down.” That’s the similarity that I see among people wherever I go.

TM I do know that there are journalists who believe that when you are writing about people who are significantly disadvantaged…you are required to supply some form of compensation. I don’t know what your take on that is.

KB: It’s something that I wrestle with enormously but, as I explained to the people of Annawadi, I will explain to you. In the work that I do, the general belief is that you don’t pay people to tell their stories. And I adhere to that. It’s not without ambivalence. But I also know that if I paid people in Annawadi for their stories it would have distorted the stories that I got. The one thing that I try to be very careful about wherever I’m working is that I don’t pull people aside and do interviews. I go with them when they work. I try not to get in people’s way to make a living, so at least [the interview] doesn’t financially deplete them. Anyway, I think it’s a better style of reporting because you get to see people in action. It’s a very troubling thing. When you read The New Yorker you should be confident that the writer hasn’t paid people to say what you want them to say.

People grieved to me in this book. People felt that if we let people know what it’s like then maybe it will get better. So it’s important to me as well that they don’t expect to get rich on this…They know that their names are in the book. They know that the story is going to convey them in good and bad [ways]. They’re not going to like everything that I’m writing. They still think it’s important that people have a better understanding of their lives. And their decision to be part of this book is courageous. And I don’t use that word lightly.

TM: Have you felt that way about subjects before? That their decision to be part of a story is courageous?

KB: Yes. Many many times.