Gore Vidal was the first living writer to get under my skin — for good and ill, but mostly for good. With his death last week, I am still puzzling out how I fell under his spell and what it might mean.

I came of age in Virginia in the 1960s and first knew Vidal as a TV personality. It was the age of talk show intellectuals and he appeared regularly on television along with Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and others. He was memorably smooth, articulate and witty. He was also very handsome, but I was a repressed gay teenager and not ready to acknowledge that. A copy of Myra Breckinridge made the rounds at study hall (along with Valley of the Dolls and The Harrad Experiment), but I didn’t read him yet, only the reviews of his work in Time.

I came of age in Virginia in the 1960s and first knew Vidal as a TV personality. It was the age of talk show intellectuals and he appeared regularly on television along with Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and others. He was memorably smooth, articulate and witty. He was also very handsome, but I was a repressed gay teenager and not ready to acknowledge that. A copy of Myra Breckinridge made the rounds at study hall (along with Valley of the Dolls and The Harrad Experiment), but I didn’t read him yet, only the reviews of his work in Time.

I witnessed his most famous TV appearance, his confrontation with William F. Buckley during the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. I was 16 and home from the Boy Scout camp where I worked as a counselor. The two men provided commentary each night, Vidal from the left, Buckley from the right. They were very testy even before the rioting broke out.

When Buckley called the student protestors crypto Nazis, Vidal said the only crypto Nazi he saw was Buckley. Buckley exploded: “Now listen, you queer. Stop calling me a crypto Nazi or I’ll sock you in the goddamn face.” Vidal remained remarkably calm. He broke into a boyish smile, as if he thought Buckley were only joking. Then the smile wavered when he understood how angry the man was.

I sat there open-mouthed, uncertain I’d heard right. One did not hear grown men call each other fags on live TV in those days. People talked about it the next day, but the newspapers couldn’t print the word. “Queer” was considered an obscenity. Of course, the accusation made Vidal only that much more interesting to me.

Two years later I actually met Vidal — by proxy anyway. I met a distant cousin, an adult Scout leader who was my date for the Eagle Scout banquet. Each new Eagle was paired with a grown-up who worked in a field the boy wanted to enter. By this time everybody knew I wanted to be a writer, and so they looked for somebody with a literary connection. And all they could find was old Bill Vidal.

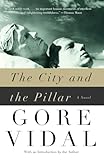

Looking back on it, I am amazed the Boy Scouts of America would think a Gore Vidal surrogate was suitable. This was after the publication of Myra Breckinridge and the fight with Buckley. But the fact of the matter is that my adult leaders knew Vidal only as a famous name and occasional guest on TV talk shows. They did not know his books. They certainly didn’t know The City and the Pillar. Bill Vidal confessed over dinner that he’d never met his famous cousin, only heard stories about him. However, he did tell me good stories about growing up in upstate New York, including the first time he ever saw an automobile.

Looking back on it, I am amazed the Boy Scouts of America would think a Gore Vidal surrogate was suitable. This was after the publication of Myra Breckinridge and the fight with Buckley. But the fact of the matter is that my adult leaders knew Vidal only as a famous name and occasional guest on TV talk shows. They did not know his books. They certainly didn’t know The City and the Pillar. Bill Vidal confessed over dinner that he’d never met his famous cousin, only heard stories about him. However, he did tell me good stories about growing up in upstate New York, including the first time he ever saw an automobile.

I didn’t get to The City and the Pillar myself until college. I can’t say I liked it. I was a gay neophyte looking for sex scenes and the novel opens with a great one: two teenage boys have hot sex on a camping trip. But Jim, the protagonist, spends the rest of the novel longing for his buddy until he finally meets up with him years later and finds he’s straight. So he kills him. (This was the original 1948 version. When Vidal rewrote it in 1965, he relented and Jim merely rapes the poor guy.)

But shortly afterward, I discovered Vidal’s essays and that’s when I really began to read him — passionately. The first book was Homage to Daniel Shays. His range of subject matter was glorious: Roman history, American history, French literature, the Kennedy family, Anaïs Nin , and yes, sexuality. The prose of his essays is erudite, surprising, and very funny. He had a stand-up comedian’s gift for placing a startlingly rude phrase in the midst of an otherwise civilized sentence. For example, in his damning review of Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex, he launches into a riff about the myth of monogamy and another book’s advice for how to keep a husband excited. “Nevertheless, by unexpectedly redoing the bedroom in sexy shades, a new hairstyle, exotic perfumes, ravishing naughty underwear, and an unexpected blow job with a mouth full of cream of wheat, somehow a girl who puts her mind to it can keep him coming back year after year after year.”

People who don’t actually read Vidal know him as only a curmudgeon, a scold, a hater. But his essays could praise as well as mock, celebrate as well as condemn. He wrote warmly and appreciatively about Eleanor Roosevelt, Tennessee Williams, Christopher Isherwood, Dawn Powell, Italo Calvino, and his own father, aviation pioneer Eugene Vidal.

His fiction can’t help looking pale in comparison to the essays. His friend and editor Jason Epstein said he was too egotistical to be a good novelist, and there is some truth in that. But Vidal was able to navigate around that difficulty by giving his egotism to his strongest characters: Julian the Apostate, Myra Breckinridge, and Aaron Burr. They are the protagonists of his best novels.

In addition to his essays I regularly read his interviews. He gave brilliant interviews. More than one person has said that Gore Vidal’s public persona — a thing of imperious authority, omniscience and dry wit — was his best fictional creation.

I almost never dream about writers, but sometime while I was writing a first novel, I dreamed about Gore Vidal. We were at a family reunion (apparently we were related) and he and I sat side by side on a log. He had just finished reading my manuscript. He told me, quietly but firmly, that the book didn’t work and there was nothing for me to do but put it aside and start a new novel. I woke up in a cold sweat, thinking: No, no, I can fix it. I can make it work — before I remembered I was not related to Vidal, we hadn’t even met, and he hadn’t read my novel. Incidentally, his dream self was right: I never was able to publish that novel.

But finally, in 1987, I did publish a novel. More novels followed, about a broad range of topics — coming of age in the 1970s, New York in the 1940s, AIDS in the 1980s — with only a gay milieu in common. Not until my fourth novel, Almost History, about a gay man in the State Department, did I notice how often I wrote about politics and history. I was as obsessed with them as Vidal was. I wrote about them differently: they were more background than foreground. But I joked that I was the low-rent Gore Vidal — or even the gay Gore Vidal. A couple of reviewers compared us, though not in my favor.

It might have produced a debilitating anxiety of influence, except I stopped thinking about Vidal around this time. Maybe that was just my way of dealing with the anxiety. And I was very busy writing my books. But the fact is Vidal became less interesting as a writer in the late 1980s and the 1990s. And his public persona became more difficult, often impossible. He grew crankier, less witty, less winning. His jokes became stale, his political positions, such as his defense of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City Bomber, unsettling.

But when I wrote Eminent Outlaws, my history of gay American writers after World War II, I found myself going back to the Vidal who first won my admiration. I was surprised by how important he was to the first half of the book, valuable not only for himself but as connecting link with many other writers. He knew everybody and he liked more of his peers than we give him credit for. He took a lot of brutal knocks as a gay writer at the start of his career, knocks that left his contemporaries, Truman Capote and James Baldwin, unhinged. Vidal remained calm, centered, and sane for much longer than they did. He really was an amazing man and an excellent writer. I was glad to rediscover that before he died.

But when I wrote Eminent Outlaws, my history of gay American writers after World War II, I found myself going back to the Vidal who first won my admiration. I was surprised by how important he was to the first half of the book, valuable not only for himself but as connecting link with many other writers. He knew everybody and he liked more of his peers than we give him credit for. He took a lot of brutal knocks as a gay writer at the start of his career, knocks that left his contemporaries, Truman Capote and James Baldwin, unhinged. Vidal remained calm, centered, and sane for much longer than they did. He really was an amazing man and an excellent writer. I was glad to rediscover that before he died.

You don’t have to read a writer to be influenced by him. Sometimes you fall in love first and don’t begin to read him until afterwards. It’s as irrational as love at first sight. Sometimes you learn that the love is deserved; sometimes it isn’t. But influence is trickier than most people think. It’s not simply a matter of one artist copying another. It can be as mysterious as the influence of the stars in astrology: they can affect our lives from a distance, as if by gravity.

I didn’t copy Gore Vidal and I never took anything from him directly. But I took great satisfaction in his prose and I learned from his example. It’s not so much the anxiety of influence or even what Jonathan Lethem calls the ecstasy of influence. No, it’s more like a feeling of kinship, a distant genealogical bond, a family relationship. Maybe, as in my dream, we are related after all.

Image Credit: Wikipedia