There is a certain type of writer whose books loom especially large as targets for hatchet jobs. A lot of critics are inclined toward gladiatorial showboating when reviewing a flawed book, and find that the temptation to indulge this tendency is exacerbated when it happens to have been written by an author of major significance or universal renown. The problem of the book’s failure is compounded by its being positioned within the broader context of its creator’s success. Here the question shifts from that of whether the book is any good to that of whether its author has any right to his or her exalted position in the first place. What’s really being asked, in other words, is something like “who is this person, and how do they keep getting away with this sort of carry-on?”

There is a certain type of writer whose books loom especially large as targets for hatchet jobs. A lot of critics are inclined toward gladiatorial showboating when reviewing a flawed book, and find that the temptation to indulge this tendency is exacerbated when it happens to have been written by an author of major significance or universal renown. The problem of the book’s failure is compounded by its being positioned within the broader context of its creator’s success. Here the question shifts from that of whether the book is any good to that of whether its author has any right to his or her exalted position in the first place. What’s really being asked, in other words, is something like “who is this person, and how do they keep getting away with this sort of carry-on?”

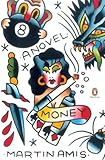

Martin Amis probably gets more of these “playing-the-man-not-the-ball” type reviews than any other living English-language writer. In fact, the Amis Hatchet Job is, at this point, a sort of minor literary genre in its own right. And, like any genre, it has its formal peculiarities and idiosyncratic requirements. As a rule, the reviewer will mention at least one (but preferably many more) of the following list of topics: misogyny; Islamophobia; dentistry; patrician contempt for the working classes; sonship of Kingsley; mentorship of Bellow; friendship of Hitchens; enmity of Barnes and/or Eagleton; comparability with Jagger; earliness of success; velvetness of trousers; greatness of Money; misapprehension of nature of own talent; distinctiveness of style; disproportionate presence of style in relation to substance; tendency of style’s distinctiveness to degenerate into self-parody. The reviewer will, before trashing this latest novel, often mention that they’ve been a fan of Amis for as long as they can remember, and that they have stuck up for him in the past when others groan at the very mention of his name. The animating question of the Amis Hatchet Job – the “whodunnit?” of the form – is usually either “How come nobody stopped him?” or “Why does he even bother?” Partly because of its inherent tendency towards exhibitionism, it can be a pretty entertaining genre, but it’s one that’s started to become a little predictable.

Martin Amis probably gets more of these “playing-the-man-not-the-ball” type reviews than any other living English-language writer. In fact, the Amis Hatchet Job is, at this point, a sort of minor literary genre in its own right. And, like any genre, it has its formal peculiarities and idiosyncratic requirements. As a rule, the reviewer will mention at least one (but preferably many more) of the following list of topics: misogyny; Islamophobia; dentistry; patrician contempt for the working classes; sonship of Kingsley; mentorship of Bellow; friendship of Hitchens; enmity of Barnes and/or Eagleton; comparability with Jagger; earliness of success; velvetness of trousers; greatness of Money; misapprehension of nature of own talent; distinctiveness of style; disproportionate presence of style in relation to substance; tendency of style’s distinctiveness to degenerate into self-parody. The reviewer will, before trashing this latest novel, often mention that they’ve been a fan of Amis for as long as they can remember, and that they have stuck up for him in the past when others groan at the very mention of his name. The animating question of the Amis Hatchet Job – the “whodunnit?” of the form – is usually either “How come nobody stopped him?” or “Why does he even bother?” Partly because of its inherent tendency towards exhibitionism, it can be a pretty entertaining genre, but it’s one that’s started to become a little predictable.

The reason I’ve been thinking about the AHJ as a genre is that I’ve been reading Lionel Asbo: State of England and feeling intermittently obliged to try my hand at it. Is Lionel Asbo a bad book? Well, it’s certainly a book with quite a lot of bad stuff in it. Every ten pages or so something happens, either at the level of prose or plot, that makes you want to hurl the thing across the room. (I read it on a Kindle, and the experience got me thinking about whether it might be a good idea for e-readers to come with a Wii remote-style adjustable wrist strap, so that this vestigial book-flinging instinct doesn’t result in domestic disaster. Those things are a lot more aerodynamic, and a lot harder, than your traditional ink-and-paper set-up.)

Firstly there’s the story itself, which, like most of its predecessors in the Amis bibliography, is all set-up and very little plot. Our protagonist is a mixed-race teenager named Des Pepperdine who lives in a council flat with his white uncle Lionel in the fictional London borough of Diston. Lionel is one of Amis’s most thorough sociopaths: someone for whom violence is both a means to various professional ends (he works as a “debt collector” of some sort, taking two apoplectic pit bulls with him wherever he goes), and a pleasurable end in itself. Des, in all but one crucial respect, is an exceptionally good kid, despite being raised by Lionel – his “anti-dad,” his “counterfather.” He’s hardworking, smart, and fundamentally decent. The one crucial respect in which he’s not a good kid, though, will probably be a deal-breaker for a lot of readers: at age 15, he frequently has full penetrative sex with his own grandmother, Lionel’s mum. If the reason why Des would want to do this is never adequately established (the whole question of statutory rape is more or less glossed over), the reason why he wants to keep it a secret is plain. What little plot there is, then, is largely concerned with the business of Des’s efforts to hide the incest from his beloved girlfriend Dawn and, more pressingly, from the eminently murder-capable Lionel. When the gran succumbs to Alzheimer’s – she’s barely into her forties, but it’s that kind of novel – she starts raving in lurid detail about all her former lovers, and this becomes an increasing cause of concern for Des. Meanwhile, Lionel wins the lotto and becomes instantaneously, farcically wealthy. He begins a relationship with a glamor model named “Threnody,” and thereby ascends to the peculiarly English status of tabloid folk anti-hero.

Amis has a great deal of fun with Lionel; in fact, he’s often clearly having more fun than the reader. He never makes the mistake of trying to mitigate Lionel’s horribleness, but it’s nonetheless obvious that he is powerfully endeared to his creation. At one point, Des is questioned by Dawn as to how he can love such a “truly dreadful person,” and it’s difficult to see his reply as anything other than Amis’s own baffled explanation for his attraction to the Lionel Asbos of the world: “‘Dawn, he’s worse than you know. But I can’t help it. It’s like you and Horace [Dawn’s racist father]. He’s a truly dreadful person too – and you love him. You can’t help it either.’” Some UK reviewers have seen Lionel as a vicious reactionary attack on the English working classes – as a kind of straw chav – but Amis’s misguided, conflicted affection for him is always puzzlingly apparent, and it’s always much more complicated, much messier, than these critics allow for. It can be difficult to differentiate such affection from a kind of fascinated disdain, but this has often been part of what has made Amis, in the past, such a compelling and troubling satirist.

One of the things that bothered me about the novel – and which led me to suspect that those who have accused Amis of a kind of patrician-anthropologist attitude toward the lower social orders might have a point – was the matter of Lionel’s speech. There are certainly some moments of linguistic brilliance here, where the cadences and rhythms of working-class Londonese are captured and subtly Amis-ized. Here, for example, is Lionel working his way into a best man’s speech at the wedding of his friend Marlon Welkway: “‘Now I always thought, Marl? Marlon Welkway? He’s not the marrying kind. Marl? No danger. Ladies’ man. Confirmed bachelor if you like …” I chuckled at this perfect presentation of Lionel’s voice, with its implied dialogic preemptions and forestallings. I didn’t need to be told what this voice sounded like, because I was already hearing it. But this was a rare moment, because throughout the novel Amis insists on interceding between Lionel and the reader, and telling the latter exactly what the former sounds like. So we’re informed that he pronounces the name “Cynthia” as “Cymfia,” and that he pronounces “myth” as “miff,” and “hyposthesis” as “hypoffesis.” We’re told that “pathetic” is pronounced “puffeh-ic-uh,” that “paddock” is delivered “with the full plosive on the terminal k,” and that “truck” is pronounced “truc-kuh (with a glottal stop on the terminal plosive).” This goes on and on, and it becomes exponentially antagonizing. It’s like trying to read while Amis looms over your shoulder, briskly clearing his throat and saying, “Now remember what I said about Lionel’s terminal plosives, all right? Let’s not forget that this is how he talks, substituting the ‘f’s for ‘th’s and so on.” (These were the moments when an adjustable Kindle wrist strap would have been most welcome.) His lack of trust in his own ability to adequately evoke Lionel’s speech, and in the reader’s competence to imagine it without these constant intercessions, is ultimately mystifying.

Amis is a notoriously riff-based writer; his signature style is one of comic accretion, and he’s at his exhilarating best when he’s exploiting the comic possibilities of elaboration and repetition. But the riffs in Lionel Asbo are often desiccated, drained of their venom, to the point where they’re in danger of sounding like harping. For a comic novel, in other words, the comedy falls too flat too often. And yet, as always with Amis, there are enough fleeting glimpses of brilliance to keep you turning the pages in anticipation of the next one. Like Lionel and Des flying into “an unserious little airport” on their way to visit Grace in Scotland. Or the description of a cat listening to a conversation “with independently twitching ears – one ear listening right, one ear listening left.” Or the reference to “parking” (i.e., burying) a deceased loved one. The strongest example of how the experience of reading Amis can vacillate so wildly between intoxication and frustration came at the end of an uncharacteristically touching section in which Des and Dawn fall helplessly in love with their new-born daughter, and with the elations and anxieties of parenthood. I was enjoying this stretch of the novel more than I had any that preceded it, and so the abrupt way in which Amis pulled the plug on it felt like a particularly reckless kind of self-sabotage: “If it’s true what they say, if it’s true that happiness writes white, then decency insists that we withdraw, passing over to the three of them a quire – no, a ream – of blank pages.” Well, I disagree with this particular authorial intervention: decency insists no such thing. If anything, it insists something like the opposite. The writing he abandons here is actually some of the least white in the whole novel.

So is Lionel Asbo a bad book? It’s certainly nowhere near Amis’s best (I see it languishing somewhere down around the lower quartile of the bibliography), and there are frequent moments when you wonder what the hell he can possibly have been thinking. But even when the riffing sounds like harping and the jokes fail to hit their marks, it’s not an unenjoyable experience. Reading Amis, I am often reminded of something my father used to say about the late Spanish golfer Seve Ballesteros, who was as wildly uneven as he was wildly talented: “Even when he’s bad, he’s a lot more fun to watch than pretty much anyone else.” Amis is all over the shop here, but even when he hits his tee shots into the car park, there’s always a significant chance that he’ll wind up with a birdie. It’s frustrating and disappointing, and frequently maddening to watch, but it’s rarely boring.