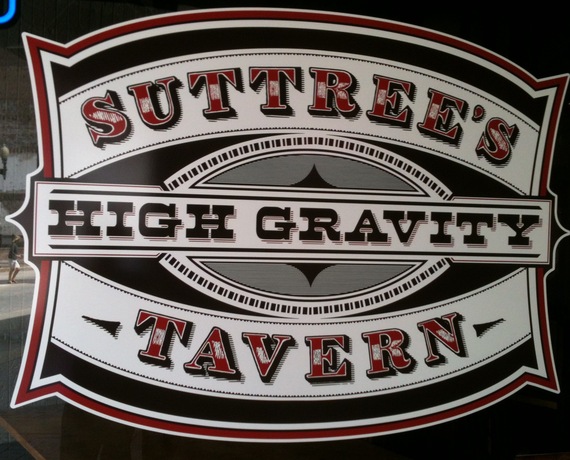

The long and honorable friendship between books and beer was toasted afresh last month when a beer tavern was named after Cormac McCarthy’s sad and funny lowlife novel, Suttree. Book and bar are both located in the city of McCarthy’s boyhood, Knoxville, Tenn.

Suttree’s High Gravity Beer Tavern is owned by the bibliophile husband-wife team of Matt Pacetti and Anne Ford, who have wisely made no attempt to belabor the Suttree connection beyond the name, thus keeping any potential kitsch-making at bay. The tavern is a deep and stylish space with saloon signage, polished wooden floors, an enormous rustic bar cobbled from old floors, and an appealing list of craft beer and wine. The semi-reclusive Cormac McCarthy, who lives in New Mexico, has been told about the new venture and wishes it well.

Suttree follows the story of Cornelius Suttree, a quiet young man who has chosen to renounce his rich, white Roman Catholic background in order to live as a fisherman on the Tennessee River and befriend a fascinating cast of back-alley boulevardiers, each of whom is sketched with tremendous solicitude and humor. Often called “Knoxville’s Dubliners,” Suttree provides an intense, forensic snapshot into Knoxville’s streets and soul. It offers the reader no racy plot or salvific climax, just an uncured slice of life. There are parts of this book that will make you laugh and others that will make your stomach coil in anguish. And while it’s a challenging read, with large slabs of poetic prose and funny words, it also contains the great themes that McCarthy’s more celebrated novels like No Country for Old Men, Blood Meridian, and The Road explore -– faith, violence, old men, death, and individual courage. Sadly, many young Knoxvillians haven’t even heard of the book. Matt has had to fend more than one query on why he’s chosen such an odd name for his bar. But for those who have read and enjoyed it, it’s not hard to see why Suttree has a special place in Knoxville’s heart.

Suttree follows the story of Cornelius Suttree, a quiet young man who has chosen to renounce his rich, white Roman Catholic background in order to live as a fisherman on the Tennessee River and befriend a fascinating cast of back-alley boulevardiers, each of whom is sketched with tremendous solicitude and humor. Often called “Knoxville’s Dubliners,” Suttree provides an intense, forensic snapshot into Knoxville’s streets and soul. It offers the reader no racy plot or salvific climax, just an uncured slice of life. There are parts of this book that will make you laugh and others that will make your stomach coil in anguish. And while it’s a challenging read, with large slabs of poetic prose and funny words, it also contains the great themes that McCarthy’s more celebrated novels like No Country for Old Men, Blood Meridian, and The Road explore -– faith, violence, old men, death, and individual courage. Sadly, many young Knoxvillians haven’t even heard of the book. Matt has had to fend more than one query on why he’s chosen such an odd name for his bar. But for those who have read and enjoyed it, it’s not hard to see why Suttree has a special place in Knoxville’s heart.

The new bar, in clientele, character, and cuisine (edamame hummus with pita chips), is a far throw from the Huddle, old Sut’s favorite boozer patronized by – prepare yourself for this lovely McCarthyian litany -– “thieves, derelicts, miscreants, pariahs, poltroons, spalpeens, curmudgeons, clotpolls, murderers, gamblers, bawds, whores, trulls, brigands, topers, tosspots, sots and archsots, lobcocks, smellsocks, runagates, rakes, and other assorted and felonious debauchees.” But is not entirely devoid of textual atmosphere. For one, it’s located on Gay Street, a hip downtown thoroughfare that features frequently and significantly in the book, and on which Suttree’s friend J Bone tells him of the death of his son, whom he has abandoned along with his wife, though we are never really told why. In another nice if unintentional touch, one long wall is painted with giant black tree trunks that recall a strange interlude in the novel when a Suttree in spiritual extremis retreats into a “black and bereaved” spruce wilderness and meets, not Satan, but a deer poacher, with whom he has a conversation that is as absurd as it is profound.

Is that a crossbow?

I’ve heard it called that.

How many crosses have you killed with it?

It’s killed more meat than you could bear.

Matt and Anne have also been asked, hopefully, if their menu has a melon cocktail. The disappointing answer is no. Perhaps this is one crowd-pleasing textual connection that might be worth exploring. The melon has an exalted place in the novel because of a ridiculous but tender scene in which a young botanical pervert call Gene Harrogate steals into the fields by nights, shucks off his overalls, and begins to mount melons in the soil. He does this for several nights till the farmer who owns the melon patch shoots him in the backside. Then, mortified at the memory of the thin boy howling in pain, he brings him an ice-cream in hospital. (This tiny but extraordinary act of kindness reminded me of young Pip in Great Expectations bringing the starving Magwitch a pork pie in the marshes.) Gene ends up in the workhouse where he meets Suttree and attaches himself to him. Together, the rat-faced but likeable felon and the ascetic, grey-eyed Suttree make for a comic but charming Felonious Monk pair. Though Suttree was published in 1979, it is set in America’s decade of conformity and suspicion, the 1950s, and one can easily imagine McCarthy gleefully adding the melon-mounting scene to his already gloriously debauched House Un-American Activities Committee.

Matt and Anne have also been asked, hopefully, if their menu has a melon cocktail. The disappointing answer is no. Perhaps this is one crowd-pleasing textual connection that might be worth exploring. The melon has an exalted place in the novel because of a ridiculous but tender scene in which a young botanical pervert call Gene Harrogate steals into the fields by nights, shucks off his overalls, and begins to mount melons in the soil. He does this for several nights till the farmer who owns the melon patch shoots him in the backside. Then, mortified at the memory of the thin boy howling in pain, he brings him an ice-cream in hospital. (This tiny but extraordinary act of kindness reminded me of young Pip in Great Expectations bringing the starving Magwitch a pork pie in the marshes.) Gene ends up in the workhouse where he meets Suttree and attaches himself to him. Together, the rat-faced but likeable felon and the ascetic, grey-eyed Suttree make for a comic but charming Felonious Monk pair. Though Suttree was published in 1979, it is set in America’s decade of conformity and suspicion, the 1950s, and one can easily imagine McCarthy gleefully adding the melon-mounting scene to his already gloriously debauched House Un-American Activities Committee.

Over the years, a Suttree subculture of sorts has sprung up in Knoxville among the small but ardent group of McCarthy aficionados. Local poet Jack Rentfro has written a song based on all the dictionary-dependent words in the book (analoid, squaloid, moiled, and so on); University of Tennessee professor Wes Morgan has set up a website, “Searching for Suttree,” with pictures of buildings and places mentioned in the book; in 1985, the local radio station did a reading of the novel in full; and for many years, Jack Neely, local historian and author, conducted The Suttree Stagger, a marathon eight-hour ramble through downtown interspersed with site-appropriate readings from the text. Last year, the independent bookstore Union Ave celebrated McCarthy’s 78th birthday with book readings, chilled beer, and slices of watermelon. During the party, when Neely read out the majestic, incantatory prologue from Suttree, several people in the audience who had shown up with their hardcover first-editions could be heard murmuring whole baroque lines from memory, and more than one pair of eyes misted over at the last line: “Ruder forms survive.”

Over the years, a Suttree subculture of sorts has sprung up in Knoxville among the small but ardent group of McCarthy aficionados. Local poet Jack Rentfro has written a song based on all the dictionary-dependent words in the book (analoid, squaloid, moiled, and so on); University of Tennessee professor Wes Morgan has set up a website, “Searching for Suttree,” with pictures of buildings and places mentioned in the book; in 1985, the local radio station did a reading of the novel in full; and for many years, Jack Neely, local historian and author, conducted The Suttree Stagger, a marathon eight-hour ramble through downtown interspersed with site-appropriate readings from the text. Last year, the independent bookstore Union Ave celebrated McCarthy’s 78th birthday with book readings, chilled beer, and slices of watermelon. During the party, when Neely read out the majestic, incantatory prologue from Suttree, several people in the audience who had shown up with their hardcover first-editions could be heard murmuring whole baroque lines from memory, and more than one pair of eyes misted over at the last line: “Ruder forms survive.”

Cormac McCarthy was not born in Knoxville. Almost 30 years ago he moved to Texas and then to New Mexico. He’s since turned down every request made by the local Knoxville News Sentinel for an interview, though, to everyone’s stupefaction, this epitome of the anti-media whore showed up on Oprah and answered questions like: “Are you passionate about writing?” Despite his reticence, Knoxville stakes first and undisputed claim to this literary giant, and rightly so. Not merely because this is where Charlie (his birth name) went to school (Knoxville Catholic High School, where he met J Long who became J Bone in Suttree); was first published (in the school magazine); was an altar boy; went to the University of Tennessee (which he dropped out of, twice), met the first of his three wives (a poet); lived with the second (a dancer and restaurateur), and overall spent about 40-odd years of his life (longer than Joyce spent in Dublin), but because Knoxville provided the manure from which his celebrated Southern Gothicism sprang. And no novel reaps a richer, more reeking harvest than Suttree. It is, to gingerly forcep a phrase from its fecal innards, “Cloaca Maxima,” often harrowingly so.

Moonshine and maggots are the holding glue in this book that opens with a suicide and ends with Suttree finding a ripe corpse crawling with yellow maggots in his bed, and whose characters consume gallons of cold beer (Suttree’s drink) and vile, home-brewed whiskey that appears to have been “brewed in a toilet.” How terrific that a bar should be called Suttree’s and what a relief they don’t serve splo whiskey. Drunks dominate this story — a hard-bitten, loyal bunch who look out for one another despite being brutalized by poverty and racism. The ties of community are sacred in the South, and it is this fundamental sense of fellowship that binds these losers. McCarthy is an unsentimental writer, but one can detect him getting slightly moist when he describes how this magnificent string of drunks faithfully visits Suttree when he is ill and broken after his forest wanderings, without a single one of them asking “if what he has were catching.”

Although Suttree is soaked in Knoxville noir, McCarthy’s most personal reference to his childhood city occurs not here but in his most recent novel, The Road. In this despairingly beautiful tale, a father and son, stand-ins for Cormac and his young son for whom he wrote the book, make their way through an almost-destroyed world swirling with ash and ruin. The pair fetch up at the father’s old house in a nameless town that is clearly Knoxville. The boy is afraid of this house with its filthy porch and rotting screens, but the father is drawn in by the phantoms of his childhood. They enter. There is an iron cot, the bones of a cat, buckled flooring. As he stands by the mantelpiece, the father’s thumb passes over “the pinholes from tacks that held stockings forty years ago,” and, suddenly, the warm remembrance of Christmases past washes over him, providing an anguished foil to his current state of homelessness. McCarthy may have scant regard for Proust as a novelist but the Proustian pull of a few pinholes is powerfully demonstrated in this passage.

To Knoxville’s great shame, this house burnt down in 2009 (The childhood home of Knoxville’s only other Pulitzer winner, James Agee, has also long been destroyed). “It was very sad,” says Jack Neely, “but there was some poetry to the fact that in the last few years the house was used by the homeless. I think Cormac McCarthy would have liked that.” Cornelius Suttree would certainly have approved.

Photo courtesy of the author.