She doesn’t look like white trash. The author photo on the back of her debut book makes Lacy M. Johnson look more like an actress, or maybe a model, with that waterfall of golden hair, that porcelain skin, those bee-stung lips and — her words, not mine — “the bluest eyes you’ve ever seen.”

But the book, Trespasses: A Memoir, leaves no doubt about its author’s white-trash bona fides. Johnson grew up on a farm in north central Missouri, where her people have lived marginal lives for nearly two centuries, managing to fail at nearly everything they try. A farm goes into foreclosure, a fireworks stand goes bust, a restaurant burns to the ground, her parents’ marriage shambles toward divorce. When she’s a young girl, Johnson’s family moves into the nearest town, Macon, and town life provides the petri dish in which her white-trash DNA will buzz and bubble to raunchy, full-blown life.

But the book, Trespasses: A Memoir, leaves no doubt about its author’s white-trash bona fides. Johnson grew up on a farm in north central Missouri, where her people have lived marginal lives for nearly two centuries, managing to fail at nearly everything they try. A farm goes into foreclosure, a fireworks stand goes bust, a restaurant burns to the ground, her parents’ marriage shambles toward divorce. When she’s a young girl, Johnson’s family moves into the nearest town, Macon, and town life provides the petri dish in which her white-trash DNA will buzz and bubble to raunchy, full-blown life.

The girl becomes aware of a social pecking order, codified by a litany of slurs townfolk use for country people: appleknocker, cletus, clodbuster, cracker, dirt eater, hayseed, hick, slue foot, yahoo, yokel and, of course, white trash. Despite her insistence that “we are not that,” by the time she’s a teenager Johnson is a member of this loathed tribe. Not that her mother didn’t try to prevent it. As Johnson tells it:

Anytime I tried to leave the house wearing dark lipstick in high school, my mother would send me straight back to the bathroom to wash it off. That makes you look trashy, she’d say. Also: cut-off jean shorts, bleaching my hair too blond, letting my roots show, swearing, wearing a dirty t-shirt to the grocery store, wearing shoes without socks, wearing skirts without pantyhose, wearing pantyhose with runs, dirty fingernails, painted fingernails, chewed fingernails, mascara, eye shadow, overplucked eyebrows, underplucked eyebrows, dangly earrings, low-cut shirts, high-cut skirts…

That’s too many rules for this girl to follow, and soon she’s shoplifting, vandalizing, getting drunk, having sex, piercing her own navel, giving herself a Mohawk, and — do you need to be told this? — getting her arms and back paved with tattoos. She will work as a cashier at Wal-Mart and she will sell steaks door-to-door, but first she must survive high school in a small town in the Midwest. It isn’t easy:

You walk to high school every day and you smoke cigarettes and cough down the peach schnapps your mama keeps hidden in the very back of the highest kitchen cabinet and even though it burns your stomach like hellfire you follow the kids to the one-block downtown and drive your truck in circles because it’s the only thing to do. You make friends with a girl your same age and she lets you spend the night at her place sometimes and you sleep real soundly in the AIR CONDITIONING. Sometimes she sneaks her boyfriend in and they have sex in the bed right next to you. One night he brings his friend over and he kisses you and claws your clothes off and you just want to sleep but his breath is stale and sweet like the beer your daddy drinks and when you try to push him off and tell him to stop he puts a pillow over your face and jams himself right up inside you and you can hardly breathe it burns so bad but there is nothing God will do.

Somehow, Johnson survives and manages to break from the tribe — one of the acts of trespassing that gives the book its title. She becomes the first member of her family to attend college, winds up earning a Ph.D. in creative writing at the University of Houston, teaches, starts getting published, produces this book. In doing so, she breaks the first commandment in the White-Trash Bible: Don’t try to rise above your raising. Because of this programming, she feels like an outsider, a fraud. “I’ve become a fluent speaker of standard American English,” she writes, “though I tend to lapse into dialect when I go home for a visit. I’ve also changed my clothes and my teeth and my hair — a slow and gradual process. I cover my tattoos any time I need to be taken seriously. I own a house in an affluent suburb and teach writing at the university. No one knows I don’t belong here.”

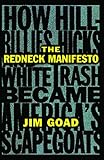

I came away from Trespasses full of admiration for its gritty passages, frustrated by its lapses into precious lyricism, and wishing we had more clear-eyed depictions of this neglected subculture. But then I caught myself. Are poor rural white people really neglected in American literature? Hardly. They might be routinely scorned, marginalized, misunderstood, and reduced to caricature, but they’re not neglected. In fact, the canon is larded with writers who’ve put the riches of white trash culture to wondrous use, including Twain, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Zora Neale Hurston, Erskine Caldwell, W.J. Cash, James Ross, Flannery O’Connor, and James Agee, to name a few. More recently, we’ve been blessed by unflinching explorations of white-trash worlds by the likes of Pete Dexter, Dorothy Allison, Cormac McCarthy, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Donald Ray Pollock, Daniel Woodrell and the recently departed Harry Crews. There has even been humor that rises far above such cartoonish tripe as L’il Abner and The Beverly Hillbillies and Jeff Foxworthy’s You know You’re a Redneck If…. In The Redneck Manifesto, Jim Goad manages to be funny, angry and in-your-face politically incorrect while defending his white-trash brethren against prevailing media stereotypes. “Multiculturalism,” Goad wryly notes, “is a country club that excludes white trash.”

I came away from Trespasses full of admiration for its gritty passages, frustrated by its lapses into precious lyricism, and wishing we had more clear-eyed depictions of this neglected subculture. But then I caught myself. Are poor rural white people really neglected in American literature? Hardly. They might be routinely scorned, marginalized, misunderstood, and reduced to caricature, but they’re not neglected. In fact, the canon is larded with writers who’ve put the riches of white trash culture to wondrous use, including Twain, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Zora Neale Hurston, Erskine Caldwell, W.J. Cash, James Ross, Flannery O’Connor, and James Agee, to name a few. More recently, we’ve been blessed by unflinching explorations of white-trash worlds by the likes of Pete Dexter, Dorothy Allison, Cormac McCarthy, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Donald Ray Pollock, Daniel Woodrell and the recently departed Harry Crews. There has even been humor that rises far above such cartoonish tripe as L’il Abner and The Beverly Hillbillies and Jeff Foxworthy’s You know You’re a Redneck If…. In The Redneck Manifesto, Jim Goad manages to be funny, angry and in-your-face politically incorrect while defending his white-trash brethren against prevailing media stereotypes. “Multiculturalism,” Goad wryly notes, “is a country club that excludes white trash.”

The term itself came into use before the Civil War. When the English actress Fanny Kemble visited a Georgia plantation in the 1830s, she reported, “The slaves themselves entertain the very highest contempt for white servants, whom they designate as ‘poor white trash.'” The term was also in use at that time in the Washington, D.C., area, where blacks and Irish immigrants competed, viciously, for the same lowly jobs. I experienced a similar three-tiered social system while living in North Carolina in the 1970s. There was still a strong after-taste of the state’s three pre-integration school systems: one for whites, one for blacks, one for Lumbee Native Americans. The fiercest fighting was never about who would reach the top because it was understood that white people, the non-trashy ones, would always run the show. The fiercest fighting was about staying off the bottom. I even saw this expressed by some unknown poet on the wall of a toilet stall in Lumberton, North Carolina:

Black is beautiful.

Tan is grand.

But white is the color of the big bossman.

I’ve traveled around the world, but nowhere — not in the hills of Burma, not on the streets of Detroit, Singapore, Havana, Hamburg, Hanoi, or the New York barrio where I now live — nowhere have I encountered people more foreign, forbidding, and fascinating than American white trash. Maybe this is because of the obvious things — their weird food and weirder religion, their nasty drinks and drugs, their lawlessness and rococo bursts of violence. Or maybe it’s because they’re so familiar they can’t help but seem exotic. I am, after all, a white Anglo-Saxon with Southern roots. My father’s father was a shabby-genteel Virginian who made a modest living as an academic in Georgia, and my mother’s father came out of the moonshine hills of southwest Virginia to become the town doctor in nearby Bluefield, W.Va., where he delivered coal miners’ babies and died broke, racked by arthritis, which he treated with self-prescribed, self-injected doses of morphine. Exotic maybe, and not too far from the trailer park, but not quite pure-T trash. I grew up in the solid middle class in Detroit and made it through college, but I’ve always been drawn to my Southern roots and the outer precincts of the white trash world. I’ve baled hay with its denizens in Vermont, pounded nails with them in North Carolina, picked apples and cut grapes with them in California. I’ve slept with a few, gotten drunk with more than a few, had one shoot a rifle into my house, watched another (a jealous female) yank out a fistful of my sister’s hair. The closer I got, the farther away I felt.

In his sometimes gassy book Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness, Matt Wray writes, “White trash names a people whose very existence seems to threaten the symbolic and social order. As such, the term can evoke strong emotions of contempt, anger, and disgust. This is no ordinary slur.”

In his sometimes gassy book Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness, Matt Wray writes, “White trash names a people whose very existence seems to threaten the symbolic and social order. As such, the term can evoke strong emotions of contempt, anger, and disgust. This is no ordinary slur.”

While it was undoubtedly coined as a slur and is usually used as one, I’ve always seen it as a badge of honor for people who have chosen or been forced to live outside the chalk lines of middle-class respectability. In a sense, these are the purest American outlaws, which is to say they are the purest Americans. They’re people who announce, in everything they say, wear, eat, drink, think, and do, that they are not one of Tom Wolfe’s “Vicks Vapo-Rub chair-arm-doilie burghers.” They are, on the contrary, the poet Philip Levine’s people, “the ones who live at all cost and come back for more, and who if they bore tattoos — a gesture they don’t need — would have them say, ‘Don’t tread on me’ or ‘Once more with feeling’ or “No pasaran’ or ‘Not this pig.'”

Which brings us back to the fact that many American writers — journalists, novelists, poets — have mined the riches of white trash. While it would be impossible to list them all, here are a half dozen of my personal favorites, along with short samples of their prose:

Marshall Frady

The journalist and biographer Marshall Frady published a non-fiction collection in 1980 called Southerners. It included “The Judgment of Jesse Hill Ford,” in which Frady tells about the peculiar travails of a writer in a small Tennessee town who had the effrontery to publish a novel called The Liberation of Lord Byron Jones in 1965, at the height of the civil rights movement, that dared to condemn the racial attitudes of the Jim Crow South. Jesse Hill Ford was promptly ostracized by his outraged white neighbors. Then, in a weird twist, he shot and killed two black people who were trespassing on his property. As part of his tortuous campaign to win back the sympathy of his fellow whites — and thus acquittal for his crime — Ford travels to a junk yard one day to plead his case to a man named Sonny Waldrop, who has a side line raising fighting dogs. Frady paints the harrowing scene:

(Waldrop) was himself strikingly evocative of some overgrown bulldog, with the same brutal impacted massiveness, the clamp of his lower jaw like the prow of a tugboat. His hair was oil-combed back to fat black locks on the nape of his neck, and he was wearing corduroy trousers that drooped below his billowing belly, his thumbs hooked in the pockets. “Hell, yeah, I got a dog out back there now,” he offered in his amiable wheeze. “Ain’t even full-grown yet, but the goddam meanest dog I ever had — I mean, two German shepherds jumped on him both at once while he was tied up to the doghouse, and he killed both their asses, by God. Wanna see ‘im? C’mon back, I’ll show ‘im to you…”

Beyond a battered sheet of corrugated tin roofing, they saw, still chained to his hovel of a doghouse, the form of a half-grown bulldog with a hide the dull gray of old dishwater, lying on top of the small rise in the cold sunlight — a third of his neck gnawed away. Still, an instant or two passed before the realization registered, as Waldrop idly nudged the dog’s stiff flanks with his boot, that it was a carcass — had been lying out here a carcass, chained to the doghouse, for at least a whole day. “Greatest goddam little ole dog I ever came by,” Waldrop whooped, and for some reason, no one seemed able to bring himself to note out loud that it was actually dead…

James Ross

Some of the best — and funniest — sketches of white trash come from white characters of the “better” classes trying to distance themselves from all that shiftless, inbred, violent, ignorant riffraff. In his only published novel, They Don’t Dance Much, James Ross puts these words in the mouth of a wealthy small-town Southerner who’s explaining the local problem to a visitor from the North:

Some of the best — and funniest — sketches of white trash come from white characters of the “better” classes trying to distance themselves from all that shiftless, inbred, violent, ignorant riffraff. In his only published novel, They Don’t Dance Much, James Ross puts these words in the mouth of a wealthy small-town Southerner who’s explaining the local problem to a visitor from the North:

“The main problem down here is the improvidence of the native stocks, coupled with an ingrained superstition and a fear of progress. They are, in the main, fearful of new things…. I think they merely dislike the pain that is attendant to all learning.”

You can almost hear the man straining to keep those “native stocks” at arm’s length.

Walker Percy

Like James Ross, Walker Percy understood that white trash offers the novelist a way into that most taboo of American topics: class. Percy’s first novel, The Moviegoer, contains what might be the greatest soliloquy on class in American literature. The novel’s disaffected hero, Binx Bolling, has a blue-blooded aunt in New Orleans who gives him this blistering lecture after he breaks the codes of his class:

Like James Ross, Walker Percy understood that white trash offers the novelist a way into that most taboo of American topics: class. Percy’s first novel, The Moviegoer, contains what might be the greatest soliloquy on class in American literature. The novel’s disaffected hero, Binx Bolling, has a blue-blooded aunt in New Orleans who gives him this blistering lecture after he breaks the codes of his class:

“I’ll make you a little confession. I’m not ashamed to use the word class. I will also plead guilty to another charge. The charge is that people belonging to my class think they’re better than other people. You’re damn right we’re better. We’re better because we do not shirk our obligations either to ourselves or to others. We do not whine. We do not organize a minority group and blackmail the government. We do not prize mediocrity for mediocrity’s sake. Oh I am aware that we hear a great many flattering things nowadays about your common man — you know, it has always been revealing to me that he is perfectly content so to be called, because that is what he is: the common man and when I say common I mean common as hell. Our civilization has achieved a distinction of sorts. It will not be remembered for its technology or even its wars but for its novel ethos. Ours is the only civilization in history that has enshrined mediocrity as its national ideal.”

Daniel Woodrell

In today’s Ozarks, as conjured by the wildly gifted Daniel Woodrell, meth is the new moonshine but there’s really nothing new under the pitiless sun. It is, always and forever, about family, tribe, and the violence that comes with operating on the margins of society’s rules and laws. Here is a chilling thumbnail sketch from the novel Winter’s Bone:

In today’s Ozarks, as conjured by the wildly gifted Daniel Woodrell, meth is the new moonshine but there’s really nothing new under the pitiless sun. It is, always and forever, about family, tribe, and the violence that comes with operating on the margins of society’s rules and laws. Here is a chilling thumbnail sketch from the novel Winter’s Bone:

Uncle Teardrop was Jessup’s elder and had been a crank chef longer but he’d had a lab go wrong and it had eaten the left ear off his head and burned a savage melted scar down his neck to the middle of his back. There wasn’t enough ear nub remaining to hang sunglasses on. The hair around the ear was gone, too, and the scar on his neck showed above his collar. Three blue teardrops done in jailhouse ink fell in a row from the corner of the eye on his scarred side. Folks said the teardrops meant he’d three times done grisly prison deeds that needed doing but didn’t need to be gabbed about. They said the teardrops told you everything you had to know about the man and the lost ear just repeated it. He generally tried to sit with his melted side to the wall.

Elmore Leonard

Most of Elmore Leonard’s crime novels take place in cities: Detroit, New Orleans, Miami, Las Vegas, Los Angeles. But his Detroit novels, in particular, make room for characters who’ve migrated from the country, in this case the white Southerners who’ve traveled the “Hillbilly Highway” (originally U.S. 23, now I-75), which runs from Appalachia right up to the all-devouring mouth of Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant and other Detroit infernos. Leonard’s white Southerner outlaws have names like Clement Mansell and Ernest “Stick” Stickley, Jr. (His black Southerner outlaws have names like Virgil Royal and Sportree and Marlys.) These white guys take a pass on the rich local music offerings, from John Lee Hooker to Aretha, Motown, The Stooges, Bob Seger, and The White Stripes. Instead they stick with Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, and Jerry Reed, the Alabama Wild Man. Here’s “Stick” doing a little down-home cooking before a big night on the town: “He fixed himself some greens with salt pork and ring baloney and Jiffy Corn Bread Mix, fell asleep watching the late movie, woke up, and went to bed.” And here’s Leonard, a master at picking the perfect detail, describing a Motor City street scene in Unknown Man #89 from 1977, when Detroit was on its long steep slide:

Most of Elmore Leonard’s crime novels take place in cities: Detroit, New Orleans, Miami, Las Vegas, Los Angeles. But his Detroit novels, in particular, make room for characters who’ve migrated from the country, in this case the white Southerners who’ve traveled the “Hillbilly Highway” (originally U.S. 23, now I-75), which runs from Appalachia right up to the all-devouring mouth of Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant and other Detroit infernos. Leonard’s white Southerner outlaws have names like Clement Mansell and Ernest “Stick” Stickley, Jr. (His black Southerner outlaws have names like Virgil Royal and Sportree and Marlys.) These white guys take a pass on the rich local music offerings, from John Lee Hooker to Aretha, Motown, The Stooges, Bob Seger, and The White Stripes. Instead they stick with Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, and Jerry Reed, the Alabama Wild Man. Here’s “Stick” doing a little down-home cooking before a big night on the town: “He fixed himself some greens with salt pork and ring baloney and Jiffy Corn Bread Mix, fell asleep watching the late movie, woke up, and went to bed.” And here’s Leonard, a master at picking the perfect detail, describing a Motor City street scene in Unknown Man #89 from 1977, when Detroit was on its long steep slide:

He had a wonderful job taking care of the Mayflower, the actual carved-in-stone name of the apartment building on Selden, in the heart of the Cass Corridor, where he could sit in his window and watch the muggings in broad daylight and the whores go by and the people from Harlan County and East Tennessee on their way to the grocery store for some greens and cornmeal.

We know Leonard’ s characters by what they eat, what they wear and how they talk, as much as by what they do. Therein lies his art.

John Jeremiah Sullivan

While Walker Percy, Elmore Leonard, and Flannery O’Connor frequently use white-trash behavior — and those who imagine themselves above it — as a way to inject sly humor into their writing, John Jeremiah Sullivan goes a different route. In “Upon This Rock,” the lead essay in Pulphead, his superb non-fiction collection from last year, Sullivan falls in with a group of buddies from West Virginia who have come to a Christian rock festival in rural Pennsylvania called Creation. Their names are Bub, Darius, Jake, Ritter, Josh, and Pee Wee, good country people who strum guitars, eat frog legs, and have accepted Jesus Christ as their personal savior. Many writers would dismiss them as white trash and treat them with condescension or outright disdain. Sullivan treats them with such unblinking candor and respect that it seems like a small miracle:

While Walker Percy, Elmore Leonard, and Flannery O’Connor frequently use white-trash behavior — and those who imagine themselves above it — as a way to inject sly humor into their writing, John Jeremiah Sullivan goes a different route. In “Upon This Rock,” the lead essay in Pulphead, his superb non-fiction collection from last year, Sullivan falls in with a group of buddies from West Virginia who have come to a Christian rock festival in rural Pennsylvania called Creation. Their names are Bub, Darius, Jake, Ritter, Josh, and Pee Wee, good country people who strum guitars, eat frog legs, and have accepted Jesus Christ as their personal savior. Many writers would dismiss them as white trash and treat them with condescension or outright disdain. Sullivan treats them with such unblinking candor and respect that it seems like a small miracle:

In their lives they had known terrific violence…Half of their childhood friends had been murdered — shot or stabbed over drugs or nothing. Others had killed themselves. Darius’s grandfather, great-uncle and one-time best friend had all committed suicide. When Darius was growing up his father was in and out of jail; at least once his father had done hard time…

But in addition to knowing violence, these young men know, and love, the natural world:

It came out that these guys spent much if not most of each year in the woods. They lived off game — as folks do, they said, in their section of Braxton County. They all knew the plants of the forest, which were edible, which cured what. Darius pulled out a large piece of cardboard folded in half. He opened it under my face: a mess of sassafras roots. He wafted their scent of black licorice into my face and made me eat one…

And:

“It’s fixin’ to shower here in about ten minutes,” Darius said. I went and stood beside him, tried to look where he was looking.

“You want to know how I know?” he said.

He explained it to me, the wind, the face of the sky, how the leaves on the tops of the sycamores would curl and go white when they felt the rain coming, how the light would turn a certain “dead” color. He read the landscape to me like a children’s book. “See over there,” he said, “how that valley’s all misty? It hasn’t poured there yet. But the one in back is clear — that means it’s coming our way.”

Minutes later it started to rain, big, soaking, percussive drops…

So there you have it: peach schnapps, rape, dead dogs, fearful native stocks, angry bluebloods, disfigured crank chefs, ring baloney, the Alabama Wild man, and people who can read the natural world like a children’s book. It is any wonder my fascination is boundless?

We would love to hear about your own favorite writers, along with brief passages from their writings on the riches of white trash. Feel free to include them below, in the Comments Section.

Image Credit: Flickr/edenpictures