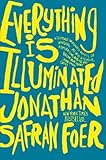

It wasn’t so long ago that critics were wondering whether the Holocaust could sustain a serious literature of its own after all the original survivors were gone. Primo Levi, Jerzy Kosiński, Paul Celan — all survivors — had written such penetrating, personal accounts of the Holocaust that many questioned whether it was necessary, even morally responsible, to write novelistic accounts second-hand. To be sure, it wasn’t that writers were afraid to try. It was that the many who did often failed miserably. Yet over the past decade, we have seen novelists like Jonathan Safran Foer, with his poignant debut Everything Is Illuminated and Michael Chabon, with The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, breath new life into genre that once seemed either too sacred or too remote to touch.

It wasn’t so long ago that critics were wondering whether the Holocaust could sustain a serious literature of its own after all the original survivors were gone. Primo Levi, Jerzy Kosiński, Paul Celan — all survivors — had written such penetrating, personal accounts of the Holocaust that many questioned whether it was necessary, even morally responsible, to write novelistic accounts second-hand. To be sure, it wasn’t that writers were afraid to try. It was that the many who did often failed miserably. Yet over the past decade, we have seen novelists like Jonathan Safran Foer, with his poignant debut Everything Is Illuminated and Michael Chabon, with The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, breath new life into genre that once seemed either too sacred or too remote to touch.

Ellen Ullman’s psychologically complex and deeply serious new novel, By Blood, doesn’t break the stratosphere of a Foer or Chabon novel, but it does come close. She creates a heart-pounding narrative that circles around an adopted American woman living in 1970s San Francisco, referred to only as “the patient.” Told through a series of psychiatry sessions, which are eavesdropped upon by our narrator — a ghoulish classics professor escaping a murky past of his own — we learn that the patient was raised by a privileged Roman Catholic family, only to discover in adulthood that her real mother is Jewish. And not just any Jew: a highly cultured and assimilated German who finds herself in the maw of Bergen-Belsen.

Ellen Ullman’s psychologically complex and deeply serious new novel, By Blood, doesn’t break the stratosphere of a Foer or Chabon novel, but it does come close. She creates a heart-pounding narrative that circles around an adopted American woman living in 1970s San Francisco, referred to only as “the patient.” Told through a series of psychiatry sessions, which are eavesdropped upon by our narrator — a ghoulish classics professor escaping a murky past of his own — we learn that the patient was raised by a privileged Roman Catholic family, only to discover in adulthood that her real mother is Jewish. And not just any Jew: a highly cultured and assimilated German who finds herself in the maw of Bergen-Belsen.

The mother, later renamed Michal, suffers all the grisly horrors we’ve come to expect from Holocaust narratives. She is raped repeatedly by a Nazi guard, and even at the camp’s liberation, she is nearly shot to death in a battle that breaks out between Jewish Zionists and the former Nazi guards. Devastated by the horrors she’s experienced, Michal gives up her daughter, the patient — whose father may be a Nazi rapist, or perhaps a Zionist hero — to a Roman Catholic adoption agency in the hope that the daughter will escape a Jewish identity entirely. When the patient tracks down Michal years later and confronts her about her adoption, Michal, now living in Israel, responds bluntly: “I wanted to make sure you would not be a Jew.”

In a relatively short book, Ullman manages to pick up a very large, and mixed, bag of a Jewish inheritance. We hear not only about the heroics of Zionist fighters, but also their failure to follow through — one charismatic leader both unifies the Jews in the camp, only to abscond to Switzerland with stolen money. There is also a Jewish doctor who, despite establishing the fact that the death camps existed in a post-war trial, also admits to having kept herself alive by helping Dr. Mengele experiment on Jews. Yet despite Michal’s own generally grim view of Jewish history, there are moments of unquestionable triumph. In one of the novel’s most poignant scenes, we hear Michal, at last, embrace her Jewish identity at the sound of Bergen-Belsen survivors singing the “Hatikva,” which would become the national anthem of Israel. “I thought: Who are these people?” Michal recounts to her daughter:

What sort of people have such determination and courage, even before all the dead have found their graves? What was giving them such strength, such hope? And the tears ran do my face, this time not with joy but with regret, and heartbreak, and longing…You see, said Michal: At that moment, and for the first time in my life, I wanted to be a Jew.

Scenes like these can be quite moving, but they can also feel like an abridged history of 20th century Jewry. So much of Ullman’s narrative is nestled around the defining issues of Jewish life in the last 100 years — whether Israel is a blessing or burden; what role the Holocaust should play in Jewish identity; the question of assimilation — that you can forget that Judaism has had another 3,000 years of history that has sustained it. Of course, it could be argued that, in the novel’s obliviousness to that longer past, it gives a more accurate depiction of how many Jews today with only a shaky knowledge of their heritage — that is, Jews like the patient — understand Jewish identity. But with a novel so learned about Jewish history (after reading several passages of Ullman’s Holocaust narrative, I was fascinated to learn that much of it was true), you wish that she would have expanded her set of Jewish identity markers. Instead, Ullman has left us with a highly circumscribed view of Jewish identity — defined solely by the nodes of the Holocaust, Israel, and assimilation.

Ullman’s novel isn’t only about Jewish identity. It is the lens through which Ullman explores a larger question: what role should blood-heritage play in anyone’s sense of self? It is here that the structure of her novel — told through talk therapy sessions, and a creepy professor who doubts the psychiatrist’s motives — makes perfect sense. For the psychiatrist, Dr. Dora Schussler, we are given a classic Freudian view of self-understanding. Only through digging up one’s repressed memories from childhood, Dr. Schussler suggests to the patient, can she finally solve all her young adulthood issues — her lesbianism, her chilly relationship with her adopted mother, her constant drive to succeed (she is already a successful financial analyst). Yet since all this is mediated through the professor, whose office sits next to Dr. Schussler’s, there is the constant undercurrent of doubt cast over Schussler’s theory. “Irreparable harm!” the professor shouts to himself at one point, as he eavesdrops on one of Dr. Schussler’s sessions. “How dare you do irreparable harm to my beloved patient!”

This tug-of-war between the professor and Dr. Schussler serves Ullman’s purposes on several levels. Both characters have their own psychological baggage, thus denying us the certainty that any one character is right. In addition to the professor’s expulsion from his university, perhaps for sexual misconduct with his students, Dr. Schussler is herself German, and is quite possibly is using the patient to expiate for “the sins of my own Nazi bastard father,” as she says at one point. But by setting the novel well after the Holocaust itself, in 1970s San Francisco, Ullman has also employed a critical narrative device that has enabled the Holocaust novel to survive, even flourish, well beyond the survivor-written testaments. The Holocaust is quickly becoming something no writer will have ever had direct experience with. So rather than create simple works of historical fiction, fashioning narratives set solely in war-ravaged Europe, Ullman, like Chabon and Foer, has ushered in a fecund new phase of Holocaust fiction. It is not only necessary that we try to recapture the morally-starved world of the actual Holocaust — something Ullman has done extraordinarily well — but that we take up the question of how much that bleak history should define our present-day lives.

Ullman is savvy enough an author to avoid giving a definitive answer, but she does offer some quite plausible ones. When the patient, tormented over the issue of who her real father is — a killer, or hero — asks Dr. Schussler for advice, she answers: “What does it matter which one your father is?” “Yes,” the patient answers, “But you can’t help but thinking. Can’t help but wonder who he was.” To which Dr. Schussler responds:

Of course…You will always think about it and wonder over it. It is part of your history, and quite an unusual history at that. I imagine you will tell many stories about it as you meet people over the course of your life. But I don’t think you necessarily have to feel too much about it, if you understand my distinction.

I think I do [says the patient].

It is an interesting and distinctive fact about you, but says nothing—

About who I am now.

Wise advice indeed.