What is Jewish life, if not unanswered questions and unending struggles? Please don’t take offense — I say this as a Jew and as, more problematically, a Jew in post-Holocaust America. I do not, in general, find myself plagued by religion; I grew up fairly lapsed and secular, absorbing more in the context of Jerry Seinfeld, Woody Allen, and Barbra Streisand than of the Mishna and Gemara, Rashi or Rabbeinu Tam. But even a modern Jew lives under the cloud and the baggage of the past — the loaded history of a people so put upon that all subsequent actions seem fraught with meaning, with responsibility, and with obligation to honor…something bigger than our daily experience. It’s a duty I feel stirring whenever I dip into the story of the Golem, interrogate one of Philip Roth’s many kvetching young men, or lose myself in the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man, a film about the futility of finding happiness in a world defined by doubt. The story of Job, the righteous yet put-upon recipient of God’s trials, remains ever-present in all these narratives, and like it or not, becomes the central problem in every piece of contemporary Jewish fiction. Why, despite our best efforts to avoid trouble, does it follow us everywhere?

In Shalom Auslander’s Hope: A Tragedy, the trouble that plagues us is history itself — and history’s cue to make itself felt is our desire to run away from it. Auslander’s version of Job, the amusingly named Solomon “Solly” Kugel, moves to an old farmhouse in the town of Stockton, N.Y., with his wife and young son. This town promises a clean slate, for it is a place “famous for nothing, presumably untouched by history, entirely unburdened by the past.” Solomon does bear one burden with him to Stockton: his ailing mother, who clings to memoirs of her time in the concentration camps despite having been born after the war’s end (and in Brooklyn, no less). For her, history gives her a story to tell, a reason to live; for Solomon, it is a story to escape, and he is more obsessed with his potential last words than any words of the past. Yet when he goes up to the farmhouse attic to investigate a rotten scent, he is confronted with history made flesh, in the form of a skeletal, craven, and crabby old woman claiming to be Anne Frank. And claiming to be her is enough — for now Solomon cannot toss her out, and she becomes his albatross, a millstone of history that he must hear, smell, and fight to forget.

In Shalom Auslander’s Hope: A Tragedy, the trouble that plagues us is history itself — and history’s cue to make itself felt is our desire to run away from it. Auslander’s version of Job, the amusingly named Solomon “Solly” Kugel, moves to an old farmhouse in the town of Stockton, N.Y., with his wife and young son. This town promises a clean slate, for it is a place “famous for nothing, presumably untouched by history, entirely unburdened by the past.” Solomon does bear one burden with him to Stockton: his ailing mother, who clings to memoirs of her time in the concentration camps despite having been born after the war’s end (and in Brooklyn, no less). For her, history gives her a story to tell, a reason to live; for Solomon, it is a story to escape, and he is more obsessed with his potential last words than any words of the past. Yet when he goes up to the farmhouse attic to investigate a rotten scent, he is confronted with history made flesh, in the form of a skeletal, craven, and crabby old woman claiming to be Anne Frank. And claiming to be her is enough — for now Solomon cannot toss her out, and she becomes his albatross, a millstone of history that he must hear, smell, and fight to forget.

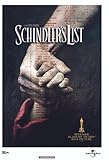

Shalom Auslander has always been a prime candidate for the position of the contemporary Isaac Bashevis Singer: he writes about the struggle to find something to believe in while wanting to shirk the stuff you can’t stand — and there’s no religion like Judaism (save for maybe Roman Catholicism) that is so much about the conflict between tradition and modernity. Auslander has his finger on this very particular kind of Jewish anxiety — the desire to start over, and to never find oneself unprepared for the world’s challenges. Solomon’s obsession with his last words is borne out of self-preservation: “He didn’t want to be caught by surprise, speechless, gasping, not knowing at the very last moment what to say…Anything but an ellipsis.” Yet how could one be anything but surprised at the appearance of dear old Anne? For Auslander’s Anne isn’t so much a character as she is a collection of reminders — the sound of her talon-like fingernails on the keyboard, her hacking cough and noxious smell trickling through the air vents of the house. What sympathy we have from her is based on our idea of her virtuosity, both as a Holocaust martyr and a preconscious yet emotionally transparent young girl. She never fully grows up, which is why Solomon never fully throws her out. Anne snarls, “It’s a lot easier to stay alive in this world if everyone thinks you’re dead.” And for Solomon, the good Jew, to toss out one of the most famous Jewish storytellers of all time on his doorstep would be beyond sacrilege. It would be a shanda fur die goy, a scandal for the goyish as well as the Jews. And Anne knows how to capitalize on Solomon’s guilt just so — “you feel guilty for not suffering atrocities,” she says. It stings, with the same acidity as that classic Seinfeld episode about making out while watching Schindler’s List, and with the same message: that if you’re not moved to tears by your history, you might as well be a denier.

Shalom Auslander has always been a prime candidate for the position of the contemporary Isaac Bashevis Singer: he writes about the struggle to find something to believe in while wanting to shirk the stuff you can’t stand — and there’s no religion like Judaism (save for maybe Roman Catholicism) that is so much about the conflict between tradition and modernity. Auslander has his finger on this very particular kind of Jewish anxiety — the desire to start over, and to never find oneself unprepared for the world’s challenges. Solomon’s obsession with his last words is borne out of self-preservation: “He didn’t want to be caught by surprise, speechless, gasping, not knowing at the very last moment what to say…Anything but an ellipsis.” Yet how could one be anything but surprised at the appearance of dear old Anne? For Auslander’s Anne isn’t so much a character as she is a collection of reminders — the sound of her talon-like fingernails on the keyboard, her hacking cough and noxious smell trickling through the air vents of the house. What sympathy we have from her is based on our idea of her virtuosity, both as a Holocaust martyr and a preconscious yet emotionally transparent young girl. She never fully grows up, which is why Solomon never fully throws her out. Anne snarls, “It’s a lot easier to stay alive in this world if everyone thinks you’re dead.” And for Solomon, the good Jew, to toss out one of the most famous Jewish storytellers of all time on his doorstep would be beyond sacrilege. It would be a shanda fur die goy, a scandal for the goyish as well as the Jews. And Anne knows how to capitalize on Solomon’s guilt just so — “you feel guilty for not suffering atrocities,” she says. It stings, with the same acidity as that classic Seinfeld episode about making out while watching Schindler’s List, and with the same message: that if you’re not moved to tears by your history, you might as well be a denier.

This is heavy stuff for a comic novel, which begs the question: does the joke work? If you’re willing to sacrifice history’s most sacred cows, and to let your imagination wander far enough to contemplate the Holocaust’s signature martyr as a squirrel-eating, bottle-throwing old crone, then yes, you’ll chuckle at Solomon’s dilemma. It’s a cheap trick of a comedic conceit, but Auslander builds the hilarious frustrations set upon Solomon like a well-stewed brisket. As Anne-as-attic-dweller becomes worse and worse, he becomes more and more frenzied even as his compassion grows. “If you don’t learn from the past,” Solomon thinks, “you are condemned to repeat it. But what if the only thing we learn from the past is that we are condemned to repeat it regardless? The scar, it seems, is often worse than the wound.” It is the scar of history, and the subsequent hope that we can heal, that makes tragedy out of modern life, and makes Anne an unmovable part of Solomon’s life. Early in the novel, Solomon’s friend Professor Jove argues that Hitler was history’s greatest optimist, and that only optimists change the world for the worst:

“Have you ever heard of anything as outrageously hopeful as the Final Solution? Not just that there could be a solution…but a final one, no less!…I tell you this with absolute certainty: every morning, Adolf Hitler woke up, made himself a cup of coffee, and asked himself how to make the world a better place. We all know his answer, but the answer isn’t nearly as important as the question…Pessimists don’t build gas chambers.”

The monsters are the ones that think you can actually revise and improve upon the past — and so to be a virtuous person, the argument follows, you must live in the past’s shadow. Such a classically Jewish problem was never so depicted, a problem created by a sense of both despair and inevitability. And therein lies the brilliance of Auslander’s novel: Hope: A Tragedy is about the fact that you can’t escape your own legacy, no matter how great your desire for a better world. Though some might argue that any book that suggests Anne Frank survived, even satirically, should be deemed verboten, the feeling you get at the close of Auslander’s novel is one of responsibility, not horror or disdain. The most famous line from Anne’s Diary, the one affixed to her image for all eternity, has been this: “In spite of everything I still believe people are really good at heart.” That’s all very well, but there’s a second line to that quote: “I simply can’t build my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death.” Perhaps Anne wanted to leave a little bit of the past behind as well — for denial of the past allows us to steamroll ahead into the future. Blindly, maybe, but still galvanized with optimism.

It brings me back to a phrase uttered over and over by my grandparents growing up — they were the children and grandchildren of immigrants, just barely out of the Holocaust’s grasp and still with enough proximity to feel its devastation. Over and over again, I’d hear them say, “So, nu?.” It can mean “what’s new?”, or it can mean “What can you do?” An expression to suggest change and stasis, hope and resignation, all at once.