Empathy in fiction is a strange thing. It is possible to experience an imaginative connection with a character in a novel that would almost certainly be beyond us were that character a real human being in the world. A character’s actions, no matter how terrible, are often secondary to the way in which he or she is presented, particularly when that character is a first-person narrator. Lolita’s Humbert Humbert is an extremely obvious — and an obviously extreme — example of this. He’s a murderer, a kidnapper, a pedophile and, in a way that manages to seem somehow independent of these attributes, a fundamentally distasteful person. And yet we want to spend time with him. We want to hear what he has to say, and not just because it’s so horrible, or because of the famously fancy prose style in which he says it. There’s a part of us that connects with him, even as we recognize that we would never, or could never, do the ugly things he does. He is, as a fictional creature, more human to us than any of his countless real-world counterparts.

Empathy in fiction is a strange thing. It is possible to experience an imaginative connection with a character in a novel that would almost certainly be beyond us were that character a real human being in the world. A character’s actions, no matter how terrible, are often secondary to the way in which he or she is presented, particularly when that character is a first-person narrator. Lolita’s Humbert Humbert is an extremely obvious — and an obviously extreme — example of this. He’s a murderer, a kidnapper, a pedophile and, in a way that manages to seem somehow independent of these attributes, a fundamentally distasteful person. And yet we want to spend time with him. We want to hear what he has to say, and not just because it’s so horrible, or because of the famously fancy prose style in which he says it. There’s a part of us that connects with him, even as we recognize that we would never, or could never, do the ugly things he does. He is, as a fictional creature, more human to us than any of his countless real-world counterparts.

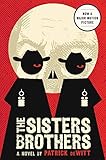

If we’re talking in purely utilitarian terms — if we stick to the basic moral spreadsheet of his actions — Eli Sisters, the narrator of Canadian novelist Patrick deWitt’s Booker-shortlisted The Sisters Brothers, is probably a worse guy than Humbert Humbert. As a professional hit man in the gold-rush era American West, he has, in partnership with his older brother, Charlie, killed an awful lot of people. And he doesn’t seem to have any particular inclination to conceal the unpleasantness of his actions from the reader (he is not, as far as it’s possible to tell, a remotely unreliable narrator). He lives an ugly life in an ugly world. About a third of the way into the novel, for instance, we see him perform an astonishingly unpleasant sequence of actions. Charlie has just shot a prospector who had been holding Eli at gunpoint. The bullet having relieved him of the back of his skull “like a cap in the wind,” the presumably (but not explicitly) dead prospector’s brain is now exposed. Eli then informs us that he “raised up my boot and dropped my heel into the hole with all my weight behind it, caving in what was left of the skull and flattening it in general so that it was no longer recognizable as the head of a man.” His rage still unsubdued, he disappears into a forest and lowers his trousers, ostensibly to check the state of his leg after its being prodded by the barrel of the prospector’s rifle. He briefly considers returning to the body to mutilate it further, but decides against it. “My pants were still down,” he recalls, “and after collecting my emotions I took up my organ to compromise myself.” This, we are informed, is a technique suggested to him many years previously by his mother as a means of dealing with his sometimes unmanageably violent temper.

If we’re talking in purely utilitarian terms — if we stick to the basic moral spreadsheet of his actions — Eli Sisters, the narrator of Canadian novelist Patrick deWitt’s Booker-shortlisted The Sisters Brothers, is probably a worse guy than Humbert Humbert. As a professional hit man in the gold-rush era American West, he has, in partnership with his older brother, Charlie, killed an awful lot of people. And he doesn’t seem to have any particular inclination to conceal the unpleasantness of his actions from the reader (he is not, as far as it’s possible to tell, a remotely unreliable narrator). He lives an ugly life in an ugly world. About a third of the way into the novel, for instance, we see him perform an astonishingly unpleasant sequence of actions. Charlie has just shot a prospector who had been holding Eli at gunpoint. The bullet having relieved him of the back of his skull “like a cap in the wind,” the presumably (but not explicitly) dead prospector’s brain is now exposed. Eli then informs us that he “raised up my boot and dropped my heel into the hole with all my weight behind it, caving in what was left of the skull and flattening it in general so that it was no longer recognizable as the head of a man.” His rage still unsubdued, he disappears into a forest and lowers his trousers, ostensibly to check the state of his leg after its being prodded by the barrel of the prospector’s rifle. He briefly considers returning to the body to mutilate it further, but decides against it. “My pants were still down,” he recalls, “and after collecting my emotions I took up my organ to compromise myself.” This, we are informed, is a technique suggested to him many years previously by his mother as a means of dealing with his sometimes unmanageably violent temper.

The remarkable thing about the scene is the way in which deWitt makes this horrible stuff seem as though it were happening to Eli. We see him not so much as the perpetrator, but as the victim, first of the prospector’s aggression, then of his own rage. When he stamps on the man’s already adequately traumatized cranium, we wince not so much for the sickening brutality of the act he commits as we do for Eli’s own sake — out of sympathy for someone who is not nearly as cool a customer as he needs to be in his line of work, and for someone whose propensity toward savage violence might reveal a deeply scarred psyche. The prospector himself barely enters into the emotional equation; he is merely the cause, and then the focus, of Eli’s rage. Empathy in fiction, as I’ve said, is a strange thing. And the fact is that Eli is an extremely likeable character. We want him to get along, even when getting along involves murdering people for no other reason than that he’s being employed to do so.

The plot is an extremely simple one: Eli and Charlie have been instructed by their boss, a ruthless businessman referred to as the Commodore, to travel from Oregon to San Francisco in order to assassinate a former associate with the delightful name of Herman Kermit Warm. They don’t know why Warm has to die, and neither do they express any real interest in the question; they simply know they have to find him via a go-between named Henry Morris and murder him. Eli wants to stop killing. It’s not that he feels any particular guilt about it, so much as that he’s just sick of the blood and the suffering and constant danger. He has little natural aptitude for or attachment to the art of murder. Eli has vague plans to open a drapery shop once the Warm assassination is complete, but Charlie — by far the more accomplished and enthusiastic killer, and the dominant brother — dismisses and ridicules Eli’s plans to settle down and go straight. We’re in familiar territory, in other words; deWitt doesn’t have much apparent interest in subverting his chosen genre.

The novel’s structure is episodic, with each short chapter detailing a tightly delineated incident, and advancing the brothers further along their trajectory towards San Francisco and the doomed, mysterious Warm. There are countless diverting episodes along the way. The brothers spend the night in an abandoned house with an old woman who appears to be a witch; the portly Eli falls for a hotel manageress who bluntly informs him she prefers less bulky men, and so he tortures himself with a 19th-century version of a crash diet; Charlie inflicts a series of debilitating hangovers upon himself and overdoes it on the curative laudanum. They meet an impressive array of vividly drawn characters on their travels, whom they as often as not rob, murder, or in some other way mistreat. DeWitt’s exploitations of the picaresque form are striking, and he has a wonderful way of exercising his comic gifts without ever compromising the novel’s gradual accumulation of darkness, disgust, and foreboding. Much of this has to do with Eli’s narration, which is a strange and lovely linguistic artifact, curiously formal in its delivery and yet intimate and unguarded. Early on, Eli suffers a grotesque swelling of his head and visits an amateur dentist who, after inflicting a series of minor atrocities on his oral cavity, introduces him to the new concept of oral hygiene. He shows Eli “a dainty, wooden-handled brush with a rectangular head of gray-white bristles” and demonstrates “the proper use of the tool, then blew mint-smelling air on my face.” Eli’s evangelical conversion to this new “method” provides a running joke throughout the book, but it is also one of the countless wonderful ways in which deWitt humanizes a narrator who would otherwise be in danger of seeming, if not quite monstrous, then certainly a very bad person. Later, he bonds with the hotel manageress through their shared enthusiasm for the newfangled brush and paste. It’s one of the novel’s many moments of quiet, restrained absurdity:

I elected to show the woman my new toothbrush and powder, which I had in my vest pocket. She became excited by the suggestion, for she was also a recent convert to this method, and she hurried to fetch her equipment that we might brush simultaneously. So it was that we stood side by side at the wash basin, our mouths filling with foam, smiling as we worked. After we finished there was an awkward moment where neither of us knew what to say; and when I sat upon her bed she began looking at the door as if wishing to leave.

The scene appears to be playing coy; the shared vigour of the tooth-brushing seems like an obvious stand-in for a more erotic intimacy. But we already suspect, and will soon find out for certain, that the woman is nowhere near as chaste as Eli wants to portray her here (she’s already had a grubby commercio-sexual exchange with Charlie upstairs), and neither is the novel itself. The scene is a sort of reverse feint, in other words, in that it seems to be doing more than it is, as opposed to doing more than it seems. It really is about Eli’s enthusiasm for the toothbrush, and his delight in sharing his enthusiasm with a woman to whom he has taken a shine. Even when he’s involved in much grimmer activities, he is a curiously innocent man. The stiff-backed composure of his language, though, is the major source of his charm. It’s hard not to smile at words like “equipment” and “method” being applied to the accoutrements of tooth brushing, and it’s impossible not to like Eli for the childlike joy he takes in them.

Eli may be a likeable guide, but the territory he takes us through is bleak and nightmarish, teeming with malice and greed, with violent lusts and blank antipathies. Comparisons to Cormac McCarthy have inevitably been made, and it’s a reasonably fair point of reference, but the connection finally has more to do with subject matter than style. It’s hard not to think of Heart of Darkness, too, what with the mounting sense of dread, the confrontation of the bestial forces beneath the veneer of civilization, and the apparently Kurtzian figure of Warm. There are moments of fierce visual potency that seem like a gift to whoever might end up directing the seemingly predestined film adaptation (I wouldn’t be surprised if the Coen Brothers were already mustering their forces). There’s a particularly chilling descriptive passage, for instance, where Eli is skinning a bear he is forced to shoot when it attacks his beloved horse, Tub. His observation of the skinned animal amounts to an eerie vision of nature as an engine of death and ruthless, unceasing assimilation. “The carcass lay on its side before me,” he tells us, “no longer male or female, only a pile of ribboned meat, alive with an ecstatic and ever-growing community of fat-bottomed flies. Their number grew so that I could hardly see the bear’s flesh, and I could not hear myself thinking, so clamorous was their buzzing.” DeWitt then inserts a visual detail which is both beautiful and utterly grotesque, and which caused me to put down the book and pause for a moment in order to savor its inspired creepiness. “When the buzzing suddenly and completely ceased,” Eli recalls, “I looked up from my washing, expecting to find the flies gone and some larger predator close by, but the insects had remained atop the she-bear, all of them quiet and still save for their wings, which folded and unfolded as they pleased.” There is something unaccountably horrible about that moment of silence and, in particular, the wings folding and unfolding “as they pleased.” It’s entirely peripheral to the narrative, and to the scene in which it takes place, and yet it somehow encapsulates the stark and singular malice of the world the novel portrays.

Eli may be a likeable guide, but the territory he takes us through is bleak and nightmarish, teeming with malice and greed, with violent lusts and blank antipathies. Comparisons to Cormac McCarthy have inevitably been made, and it’s a reasonably fair point of reference, but the connection finally has more to do with subject matter than style. It’s hard not to think of Heart of Darkness, too, what with the mounting sense of dread, the confrontation of the bestial forces beneath the veneer of civilization, and the apparently Kurtzian figure of Warm. There are moments of fierce visual potency that seem like a gift to whoever might end up directing the seemingly predestined film adaptation (I wouldn’t be surprised if the Coen Brothers were already mustering their forces). There’s a particularly chilling descriptive passage, for instance, where Eli is skinning a bear he is forced to shoot when it attacks his beloved horse, Tub. His observation of the skinned animal amounts to an eerie vision of nature as an engine of death and ruthless, unceasing assimilation. “The carcass lay on its side before me,” he tells us, “no longer male or female, only a pile of ribboned meat, alive with an ecstatic and ever-growing community of fat-bottomed flies. Their number grew so that I could hardly see the bear’s flesh, and I could not hear myself thinking, so clamorous was their buzzing.” DeWitt then inserts a visual detail which is both beautiful and utterly grotesque, and which caused me to put down the book and pause for a moment in order to savor its inspired creepiness. “When the buzzing suddenly and completely ceased,” Eli recalls, “I looked up from my washing, expecting to find the flies gone and some larger predator close by, but the insects had remained atop the she-bear, all of them quiet and still save for their wings, which folded and unfolded as they pleased.” There is something unaccountably horrible about that moment of silence and, in particular, the wings folding and unfolding “as they pleased.” It’s entirely peripheral to the narrative, and to the scene in which it takes place, and yet it somehow encapsulates the stark and singular malice of the world the novel portrays.

The book becomes incrementally darker the closer the Sisters boys get to tracking down Warm, but it never comes close to being overwhelming, or even, finally, all that disturbing. For all that Eli’s narrative is beautifully composed, and for all the vividness of deWitt’s depictions of mid-19th-century California as a hellish chaos of gold-rush greed, the novel feels, in the best sense, like a high-grade entertainment. The darkness it conjures is closer to Frank Miller than Cormac McCarthy. Even its most troubling moments have a cartoonish aspect to them. The depiction of the removal of Tub’s infected eye by a spoon-wielding stable hand, for instance, is unflinchingly graphic, but there’s a sly preposterousness to the scene in the first place, a knowing gratuitousness, that makes it more gross than genuinely harrowing. Similarly, the passage in which Warm dictates the words to be inscribed on a friend’s tombstone refuses to be fully serious even as it stares down life with seemingly Nietzschean intensity. “Most people,” he intones, “are chained to their own fear and stupidity and haven’t the sense to level a cold eye at just what is wrong with their lives. Most people will continue on, dissatisfied but never attempting to understand why, or how they might change their lives for the better, and they die with nothing in their hearts but dirt and old, thin blood — weak blood, diluted — and their memories aren’t worth a goddamned thing.” By the time Warm’s dictation reaches its bombastic conclusion (“There is no God”), it has long since been tipped over into absurdity by its sheer length and grandiosity, both of which attributes render it comically ill-suited to tombstone inscription. A comparable effect is achieved elsewhere, when Warm recalls his sociopathic father, a German inventor who was forced to flee to America due to his “specific area of deviancy” (presumably sexual, although never actually identified). The elder Warm’s inventions are insane, but strangely believable. One of them provides a disturbing distillation of the desires for power, wealth, and primacy that fuel the savage economy the novel portrays. “He invented,” Warm tells Eli, “a gun with five barrels that fired simultaneously and covered three hundred degrees in one blast. A hail of bullets, with a slim part, or what he called Das Dreieck des Wohlstands — The Triangle of Prosperity — inside of which stood the triggerman himself.” There are many moments of genuine humour in The Sisters Brothers, but deWitt is also very good at this kind of queasily unfunny joke. The kind of joke, in other words, which is in no more or less terrible taste than history itself.

There is a sense, toward the end of the novel, that deWitt has not done quite as much with his endearing narrator and his compelling narrative style as he could have. The a-to-b of the plot is a little too straightforward to be satisfying, and there’s not much to be had in the way of an emotional pay-off in the jarringly sweet final pages. Despite the depravity and violence he depicts (and is responsible for), Eli never gets much beyond establishing that the world is a dark and unpleasant place, and that he vainly wishes it could be otherwise; there’s not, in this sense, ultimately a whole lot of moral heft. But perhaps that doesn’t matter all that much when a book is so consistently enjoyable as this. The Sisters Brothers is as entertaining a novel as I have read in a long time, and there’s always a lot to be said for entertainment, even on the Booker shortlist.