1.

On pages 142-145 of my novel, The Funny Man, through the thin scrim of fiction, I write about the final hours of my father’s life. The scene takes place in a hospice, where the funny man’s father is unconscious and dying of cancer and a woman with a harp comes in and asks if she can play some music, that there is research showing that harp music brings the terminally-ill and imminently-dying ease. When this scenario happened in real life, the tiny sliver of my brain not weighed down by the anvil of grief filed this away as an interesting little tidbit that I should look into sometime, but I never did, until just now, and it turns out that it’s true.

On pages 142-145 of my novel, The Funny Man, through the thin scrim of fiction, I write about the final hours of my father’s life. The scene takes place in a hospice, where the funny man’s father is unconscious and dying of cancer and a woman with a harp comes in and asks if she can play some music, that there is research showing that harp music brings the terminally-ill and imminently-dying ease. When this scenario happened in real life, the tiny sliver of my brain not weighed down by the anvil of grief filed this away as an interesting little tidbit that I should look into sometime, but I never did, until just now, and it turns out that it’s true.

Go figure.

Because by design I live an uninteresting and largely uneventful life, very, very little of the book is autobiographical. My main character, a stand-up comedian called only “the funny man,” is rich, famous, and on trial for murder. I’m none of these things, so when the scene popped up during drafting, I was surprised. I didn’t know that my story also belonged to my character until the moment it hit the page and I didn’t have an overwhelming urge to delete it.

Being present at my father’s death was the most awful (in both the “awful” and “awe-full” senses of the word) moment of my life. I won’t recount it here. It’s all in the book, pretty much. At the same time I also recognized it as hopelessly mundane, beyond common all the way into cliché. Looked at objectively, losing one’s father to cancer while in your thirties is hardly the biggest tragedy in the world, particularly when he’s been a better-than-good father right up to the end.

Like so much of our lives, these things are important to ourselves, but difficult to make interesting to someone else, one of those “you had to be there and be me” moments. Nonetheless, there the memory was at the precise halfway point in drafting the book, the moment a project is either going to get up on its feet and make a move toward the finish line or become another forgotten file on the hard drive. I remember crying as I wrote the scene, just as the funny man is on the page, just as I did when that woman with the harp played for all of us in my father’s hospice room. I don’t mistake this for some kind of testament to the power of my own prose. It’s the simple revisiting of grief that happens to anyone who has suffered a loss, the periodic return of a sense that something vital is missing.

In the immediate aftermath of my father’s death, my predominant emotional state was… nothingness. I went back to work a week after his passing, and would stand in front of the classroom, occasionally outside myself, wondering how I could be so calmly delivering the material to my students, wondering if that guy doesn’t know that his father is dead. We attribute this sort of behavior to bravery, but this seems misplaced to me. It’s numbness, plain and simple, like when you break your arm, and you don’t feel it at first, the body’s method of self-protection.

Ultimately, the pain arrives in a way that makes you feel it, at first often and steadily escalating, like waves breaking in a rising tide. After a time, it recedes, and when it’s more absent than present, there’s even moments where you miss it, a companion you never quite cared for, but got used to having around.

Something like the release of your first novel, as exciting as it can be, is the kind of thing that invites grief’s return, though with six years having passed, it’s a feeling that can be picked up and examined and is in some ways more reparative than damaging.

My father’s presence in my life was often more implied than explicit. When I was growing up, he worked, a lot, busy providing more than the family needed. If I was in trouble, mom was the disciplinarian, with dad the ultimate authority (“just wait until your father comes home”). Our longest one-on-one conversations were on shared lift rides while on ski vacations. At college and afterwards, if I called home, I talked to mom and trusted that she relayed all the relevant information to him. We went to Bulls and Blackhawks games together and fought over the last piece of chocolate cake. I don’t remember any heart-to-heart conversations, though I don’t think we ever doubted our fidelity to each other.

I was not always physically present for him, either, I recall, with some measure of shame. He died in November, but it all started the February before that, with a surgery to remove a golf-ball-sized tumor on his pituitary gland. Normally pea-sized, the pituitary dangles from the brain, housed in a cavity in the middle of the skull. The tumor had filled that space and then some, eroding bone in the sinuses. The tumor announced itself by putting pressure on his optic nerve, clouding his vision. The surgery was done transphenoidally, the surgeon’s tools snaking up through his nose to the sinus cavity to carve out as much of the tumor as deemed safe. I should’ve gone home for the procedure, but I didn’t. I had a sales conference for a forthcoming book scheduled at my publisher’s who talked and acted like they loved me (it didn’t last), which meant I was about to be treated like a big shot, an all-too-rare occurrence in any writer’s life. This decision had my father’s blessing because he was a stoic, and making a big deal out of it wasn’t his way. Plus, it wasn’t all that much to worry about, he’d skied eleven days that January and was a picture of total health, save this fluky tumor that might’ve been slowly growing for twenty-five years. Or maybe he was just nervous and all of us hovering would’ve made him more anxious. I don’t really know. My mom called as I was driving to the airport for my trip, letting me know that the surgery went perfectly, that all our confidence had been properly placed.

The next morning in my meetings with sales, marketing, and editorial, we plotted my book’s takeover of the world. Our dreams for its success could barely be contained by the conference room walls. The horizon of possibility stretched endlessly, just as it does for every book before it meets its actual audience.

But leaving the last meeting, I checked my cell and saw six missed calls from my mom. Her message on my voicemail said that in the night, my father had what they were calling a “brain episode,” that he was alive, but something had gone wrong and I needed to get home.

2.

Because of the nature of our relationship when my father was living, there are times even now, six years after his death, that I will forget he’s gone because he was never constantly present in my life. I took him for granted, I’m sure, as is likely the way of all kids blessed with good parents, but I’ve come to realize how his life looms over mine, what has been lost.

He’s the one who set me on the path to being a writer, picking Rhetoric as my field of study out of the college catalog after I’d farted around for two years, switching majors seven different times. I think he imagined it as good training for the lawyer I was to become (like him), but it introduced me to the joys and frustrations of writing creatively, which managed to stick. After graduation and two years of paralegalling in a law firm very much like the one he practiced in, I didn’t think he was disappointed exactly that I chose an MFA over law school, but I imagined in the back of his mind, he wondered how I was going to pull it off.

The so-called “brain episode” didn’t kill my father. No, that would be the work of a coincidence too great even for fiction, an unrelated lung cancer that metastasized and ultimately first presented in his spine. That summer, post-brain episode, within weeks, a backache transformed into excruciating pain, un-dulled by pharmaceutical-grade morphine and dilaudid. I was present for that in the hospital, his agonized screams, foam collecting at the corners of his lips, drying into crust. I thought that someone needed to smother that guy with a pillow, then I remembered he was my father, despite the lack of resemblance to the man I knew.

The blessing, the irony, is that because of the brain episode doing a number on his short term memory, following spinal surgery that wasn’t going to cure him, but managed to alleviate the pain, my father recalled none of it. (Though I can’t forget it.) Each morning, the day before was like a dream, half-remembered images slipping quickly away. Sometimes we weren’t even sure if he remembered that he had cancer.

The brain episode had changed him in other ways as well, a fifteen degree shift of his personality into someone more outwardly friendly, chatting up the van driver on his way to rehab, for example. My mother often accused him of sliding into one of his “intellectual funks,” which made him seem non-present in a given moment, which I’m now certain was him “working” a particular tricky case over in his head, a trait I know I share since one of my more frequent answers to my wife’s questions is “huh?”

But post-episode, the funks were gone. Once, when I was home visiting I even saw him lol’ing at the comics page of the Chicago Tribune, each corny punch line somehow landing with tremendous force. I didn’t know anyone actually laughed at the funny papers, but there he was, enjoying every last bit of it, up to and including Family Circus. He’d become the perfect audience.

I’ve given this scene to a character in a novel I’m trying to finish right now. I’m sort of curious to see how it turns out for him.

So this new guy wasn’t exactly my father, per se, but he was a good dude to be around and I spent as much time with him as possible. By the time my book came out that fall, it was clear he was dying, sick from the chemo and the cancer, constantly annoyed by the clamshell back brace he couldn’t take off because the surgeon had removed so much of his spine. I went home for a week to see him and for a book release party he was too sick to attend. Many of the faces at the party were the same at the funeral less than six weeks later. I didn’t kid myself that these people had any interest in a parody of writing advice books. I knew that all those books purchased were out of obligation, loyalty to my mother and father, more than anything else, but don’t think I wasn’t grateful. My Bookscan numbers for the greater Chicago area were fantastic that week.

Sometime after he died, I couldn’t tell you how long, either a day after or a year later, my mom gave me a folder overflowing with paper. I recognized the type of folder from his briefcase stuffed full of case files, dropped on the entryway floor every evening to announce his arrival home, well-after my brother and I had been fed, not more than an hour before my bedtime. The glue at the folder’s seams was dried and splitting. Inside the folder were my stories and articles, some of them dating back to my undergraduate days, things never published, things I didn’t even remember writing that filled me with shame to even be reminded of their existence, mixed with more recent, web-published pieces, printed out by his secretary at his behest. Looking at it, I had what I think we literary types call an epiphany.

My father was a fan. I hadn’t known. Or if I’d known, I hadn’t thought of it that way. Looking more closely at the files, I saw that they weren’t comprehensive, that some sort of selection process was at work. It definitely wasn’t what I would’ve picked for my career retrospective. I figured that his collection and curation of my work was his way of holding the person I’d become closer, to understand me better. I just sort of wish we’d talked to each other about it. I’ve kept the folder and look through it every so often, wondering if there might be a note or comment from him that I’ve overlooked, but whatever he thought about my writing died with him. That he kept so much of it so close speaks loudly, but not necessarily clearly.

It would be nice to think that he’s looking down on me, beaming with pride, but I don’t believe in that particular story. He would’ve been proud, that I know, but he’s not here, so this is just another one of those things we’re both going to miss.

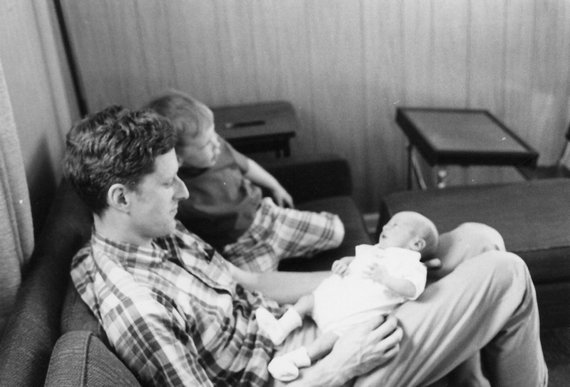

Image: The author as an infant on his father’s lap as his brother looks on