1.

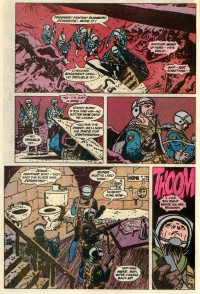

The single greatest panel in the long history of Batman comics does not feature Batman or contain any reference to him. In Batman #406 (on newsstands April ’87), the third issue of Frank Miller’s classic Batman: Year One storyline (and the basis for the 2005 Batman movie franchise re-boot Batman Begins), Batman, on the run from a crooked Gotham police force, finds himself cornered in an old abandoned apartment building. The mayor (a large, pockmarked man who is always depicted wearing a Mickey Mouse pin on his lapel), desperate to capture or kill our hero, orders an extensive bombing of the building. Over the next two pages there are explosions and quite a bit of fire. A SWAT-like group of well-armed officers inspect the remnants, ordered to shoot on sight: “go for the chest, we’ll need his face for identification.” Naturally, he picks them off one by one, finally managing to escape under the cover of a flock of bats (summoned by a mysterious button on the bottom of his shoe, of course). Standard superhero fare for the most part – except for one startling and unsettling moment on the bottom of the sixth page.

The single greatest panel in the long history of Batman comics does not feature Batman or contain any reference to him. In Batman #406 (on newsstands April ’87), the third issue of Frank Miller’s classic Batman: Year One storyline (and the basis for the 2005 Batman movie franchise re-boot Batman Begins), Batman, on the run from a crooked Gotham police force, finds himself cornered in an old abandoned apartment building. The mayor (a large, pockmarked man who is always depicted wearing a Mickey Mouse pin on his lapel), desperate to capture or kill our hero, orders an extensive bombing of the building. Over the next two pages there are explosions and quite a bit of fire. A SWAT-like group of well-armed officers inspect the remnants, ordered to shoot on sight: “go for the chest, we’ll need his face for identification.” Naturally, he picks them off one by one, finally managing to escape under the cover of a flock of bats (summoned by a mysterious button on the bottom of his shoe, of course). Standard superhero fare for the most part – except for one startling and unsettling moment on the bottom of the sixth page.

The SWAT-like team is scavenging the building, and a group of them stumble upon a plain room in the basement. There’s a sink, a toilet, a stripped bed, and a table. The few personal effects are religious in nature: a “God is…” poster, a “Honk for Jesus” bumper sticker, two crucifixes and a medallion affixed to the wall, a statue of the Virgin Mary, and an open Bible on the table. “Super must’ve lived here,” one of the officers comments. “Nobody home now,” muses another. “Nothing here, men. We’re coming back up,” a third says with finality. They leave. We will not see the room again. We will never hear from the super. If he exists, it is only in the spaces afforded between the relics of his room. If he exists, it is only in our imagination.

2.

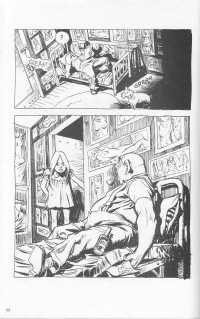

This tradition of the tragic super (this irony should not be lost on anyone) stems all the way back to one of the first graphic novels, Will Eisner’s seminal 1978 A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, a collection of four stories set in the Bronx of the 1930s. The third – titled simply “The Super” – focuses on the life of a large, surly, old super named Mr. Scuggs. He has one true friend, his dog Hugo; he has a tattoo of “mom” inscribed inside a heart. The hot water is broken; a woman named Ms. Farfell complains that her niece can’t take a bath in ice-cold water (she’ll catch new-monia). She appears wrapped tightly in a towel, wearing an expression that would have caused Humbert Humbert to violently convulse. The super’s eyes linger on her before he leaves.

This tradition of the tragic super (this irony should not be lost on anyone) stems all the way back to one of the first graphic novels, Will Eisner’s seminal 1978 A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, a collection of four stories set in the Bronx of the 1930s. The third – titled simply “The Super” – focuses on the life of a large, surly, old super named Mr. Scuggs. He has one true friend, his dog Hugo; he has a tattoo of “mom” inscribed inside a heart. The hot water is broken; a woman named Ms. Farfell complains that her niece can’t take a bath in ice-cold water (she’ll catch new-monia). She appears wrapped tightly in a towel, wearing an expression that would have caused Humbert Humbert to violently convulse. The super’s eyes linger on her before he leaves.

Instead of fixing the hot water Scuggs heads into his room, a small basement affair much like the one in Gotham City. Pornographic pictures cover the walls of his room. We see him feed his dog and then proceed to drink a beer and flip through a handful of dirty pictures. There’s a knock on the door – it’s the beautiful young niece from before, and she offers him a “peek” for a nickel. He accepts. She flashes him, and then gives his dog a piece of candy. While his back is turned she grabs his moneybox and runs. He yells for Hugo – Hugo is dead; the girl’s candy was poisoned. He chases her, cornering her in a crowded tenement alley. He is powerless to do anything for no one would believe him – cries of “murderer!” and “animal!” follow him as he stumbles away. Dejectedly, he stokes the flames of the hot water heater before slumping into his room. Crying, he kneels to hold his dead dog. The police knock on the door. He gets a gun and shoots himself in the temple. The last page shows the girl sitting on the stoop, counting her money, and humming. A sign in the basement window reads “super wanted.”

3.

In How Fiction Works, James Wood characterizes a “true” detail as one possessing a quality he terms “thisness,” part gravitas and part insight: “By thisness, I mean any detail that draws abstraction toward itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability, any detail that centers our attention with its concretion.” He goes on to cite examples from the usual stalwarts: Emma Bovary fondling a pair of satin slippers in Flaubert, the “Kendal green” of Shakespeare’s Falstaff, Mr. Casey’s permanently bent fingers in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. These details are great, he argues, because they are able to exist within themselves, able to expound upon a mostly scattered notion of “reality” in a way that somehow seems truthful. The open bible sitting idly on the table, an inconsequential nugget in a genre not known for reflection is as well placed as anything Joycean; Mr. Scuggs “mom” tattoo as heartbreaking as anything Flaubertian.

In How Fiction Works, James Wood characterizes a “true” detail as one possessing a quality he terms “thisness,” part gravitas and part insight: “By thisness, I mean any detail that draws abstraction toward itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability, any detail that centers our attention with its concretion.” He goes on to cite examples from the usual stalwarts: Emma Bovary fondling a pair of satin slippers in Flaubert, the “Kendal green” of Shakespeare’s Falstaff, Mr. Casey’s permanently bent fingers in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. These details are great, he argues, because they are able to exist within themselves, able to expound upon a mostly scattered notion of “reality” in a way that somehow seems truthful. The open bible sitting idly on the table, an inconsequential nugget in a genre not known for reflection is as well placed as anything Joycean; Mr. Scuggs “mom” tattoo as heartbreaking as anything Flaubertian.

That Miller’s panel appears in a super-hero comic is almost some kind of glorious joke, like a Kerouac reference on the Disney Channel (Selena Gomez’s boyfriend on the hit show Wizards of Waverly Place is named Dean Moriarty). It’s the kind of detail that one can easily miss, and one would imagine most did. That’s certainly not a knock on the comics; no one buy’s a ticket to The Fast & The Furious for wry poofs of background detail, just like you wouldn’t purchase a Batman comic in hopes of spotting something so elegant that it could bring you to tears. You and me and everyone we know just want to be entertained, and that’s all well and good, but just because something so beautiful appeared in something traditionally not is no reason to overlook it – if anything it is all the more reason for commendation.

4.

Things in mainstream comics are changing. The next Spiderman (in Marvel’s Ultimate Spider-Man series) will be a half-black, half-Hispanic teen named Miles Morales, and in September DC comics is rebooting their entire franchise, dialing every issue back to number one and sweeping decades worth of continuity under the rug. Batman is an American icon, as much as George Washington or Coca-Cola, and next month he gets to start over (which is nice – a lot of shit has happened to him in the last twenty years). When Bruce Wayne looks in a mirror he might just see Jay Gatsby staring back, except Jay will never get a do-over (there will always be another Great Gatsby movie, but the ending will always be the same). It seems obvious to say, but wouldn’t we all like that chance to start from issue one, with a whole slew of villains and love interests and story arcs to cover? The tragedy, and beauty, of life is that we can’t. Our redemption lies not in our pasts but in our futures, much like the faceless super in an abandoned tenement in Gotham City.

Note: The above images first appeared in Batman #406, written by Frank Miller, illustrated by David Mazzucchelli, colored by Richmond Lewis, and lettered by Todd Klein, and A Contract With God, and Other Tenement Stories, written and illustrated by Will Eisner.