1. Awful But Cheerful

In my family we remember the birthdays, not the death days, of our lost ones. My father’s father passed away in early February 2010, but we remember him on July 4th. Don Hernán used to say, when we called him to wish him a happy birthday at his beach house in Chile’s coastal town of Zapallar — by then he had already written his morning’s reflections on the Lipton tea bag wrapper from his breakfast tea and was wearing his cream turtleneck and navy blazer with brass buttons over charcoal slacks, his white beard trimmed and his blue eyes a few shades lighter than the sea hitting the rocks below his house — that he loved the United States because that was a country that knew how to celebrate his birthday.

To celebrate the 100th birthday of American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), Farrar, Straus and Giroux published three new Bishop volumes in February of this year: Poems edited by Saskia Hamilton, Prose edited by Lloyd Schwartz, and Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker: The Complete Correspondence edited by Joelle Biele.

To celebrate the 100th birthday of American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), Farrar, Straus and Giroux published three new Bishop volumes in February of this year: Poems edited by Saskia Hamilton, Prose edited by Lloyd Schwartz, and Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker: The Complete Correspondence edited by Joelle Biele.

Many critics and readers have welcomed the updated Poems and Prose, and I am especially grateful for the accompanying “Editor’s Notes” and “Notes on the Texts” clarifying which work Bishop published during her lifetime and which pertains to the other group of posthumously published prose pieces, incomplete drafts, and “manuscript poems.” The facsimiles of a handful of her manuscript pages are also helpful and will inspire pilgrimages to her archives at Vassar, Harvard, and elsewhere.

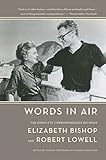

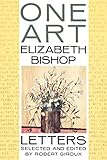

Bishop’s correspondence with The New Yorker is lively, not least because Elizabeth Bishop was a fantastic letter writer, as we know from the letters selected and edited by Robert Giroux in One Art, as well as from her correspondence with Robert Lowell collected in Words In Air. But I wish an appendix with a list of her New Yorker poems with publication dates had been included (for now the index will have to do). The rejection letters are wonderful, especially those with footnotes indicating where the piece was ultimately published, and they seem to increase steadily in word count as Bishop’s career unfolds.

Bishop’s correspondence with The New Yorker is lively, not least because Elizabeth Bishop was a fantastic letter writer, as we know from the letters selected and edited by Robert Giroux in One Art, as well as from her correspondence with Robert Lowell collected in Words In Air. But I wish an appendix with a list of her New Yorker poems with publication dates had been included (for now the index will have to do). The rejection letters are wonderful, especially those with footnotes indicating where the piece was ultimately published, and they seem to increase steadily in word count as Bishop’s career unfolds.

Dissenters of the new Bishop volumes protest the hauling out of ever more material from her archives that she never meant for us to have on our nightstands. It is a distraction from her best work, the work she published, they argue. In preparation for this stance, Saskia Hamilton, the editor of Poems, includes a note to “Appendix I: Selected Unpublished Manuscript Poems” that begins:

Elizabeth Bishop foresaw that some of her uncompleted work might be published after her death. Her will grants her literary executors “power to determine whether any of my unpublished manuscripts and papers shall be published and, if so, to see them through the press.”

The debate will roar on in some circles, and meanwhile the 2011 FSG volumes will encourage renewed assessments of Bishop’s artistic development and the arc of her work. She is among our pillars of postwar, indeed twentieth-century, poetry, and new editions, biographies, and critical studies are to be expected.

What would Bishop say about all the fuss?

The concluding lines of her poem “The Bight” — first published in the February 19, 1949, issue of The New Yorker with the poet’s note “[On my birthday]” — offer a possible response regarding such commemorations, large and small:

Some of the little white boats are still piled up

against each other, or lie on their sides, stove in,

and not yet salvaged, if they ever will be, from the last bad storm,

like torn-open, unanswered letters.

The bight is littered with old correspondences.

Click. Click. Goes the dredge,

and brings up a dripping jawful of marl.

All the untidy activity continues,

awful but cheerful.

She is clearly not a fireworks and champagne kind of birthday girl. The image of boats piled up in the bight, “not yet salvaged, if they ever will be” and compared to “torn-open, unanswered letters” suggests the poetic voice’s weariness at marking another year when not having concluded, even confronted, the previous. “The bight is littered…” is a line that recalls Baudelaire’s poem “Correspondences” and the difficulty of using words as symbols to make poems that seek infinity in the face of nature’s triumphant reach. The final two lines, which Bishop chose as her epitaph, conclude with a twist and the beginnings of a smile: “All the untidy activity continues, / awful but cheerful.” By choosing the last two lines of “The Bight” for her gravestone, Bishop, her humor and bite unflagging, closes the circle between her birthday and death day.

Another Bishopian centenary is on the horizon, the death of her father in September 1911 from Bright’s disease, an old-fashioned medical term referring to a catch-all of kidney dysfunctions. Bishop was eight months old. Her father’s death sent her mother into a tailspin of breakdowns and hospitalizations that landed her permanently in a mental hospital five years later. Bishop, suddenly parentless and of kindergarten age, lived mostly with her beloved maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia (a nine-month stretch with her father’s parents in Worcester brought on asthma, eczema, and other ailments) until she left for Walnut Hill boarding school in 1927 followed by Vassar College. She received a modest income from her father that allowed her to pursue poetry full time with the supplement of fellowships, paid writing jobs, and teaching stints.

Her father’s death coupled with his alcoholism, which ran in the family, loomed throughout Bishop’s life. On January 17, 1951, less than a month before her fortieth birthday, she wrote to Dr. Anny Baumman, her physician in New York to whom she dedicated her second collection A Cold Spring, about her recent struggles with drinking, “an emotional upset of some sort,” and her loneliness:

I am sorry this is such a stupid letter. I simply can’t seem to think very straight about this, except I know I want to stop. I am exactly at the age now at which my father died, which also might have something to do with it.

In February 1951, Bishop survived turning 40 years old, the age of her father at his death. By March things had taken a turn for the better: she was awarded the $2,500 Lucy Martin Donnelly Fellowship by Bryn Mawr — Katharine Sergeant Angell, her editor at The New Yorker, was “instrumental” to her winning the award — and in November she wrote a letter about “this crazy trip” to Robert Lowell from the Merchant Ship Bowplate stationed off the coast of Brazil, the country that would accidentally become her home for more than 15 years and would inspire a significant output of poems, stories, and translations.

2. The Terrible Thing

The not thinking straight that Bishop describes in her letter to Dr. Baumman, the fixating on being “now exactly at the age” or moment when, the anniversary of the terrible thing that happened or didn’t happen, I know this. The same week I received my copies of the new Bishop volumes edited by FSG, in early March 2011, I took my three-year-old son Théo to the emergency room.

It was a Friday afternoon, he had been fighting the stomach flu for a week, and when his eyes rolled back to their whites while his head nodded as if he were going to fall asleep, or lose consciousness, I called my husband Vlad at work. We left our younger son Max with my mother and drove the eight minutes to the hospital, the same one where Théo was born and where Vlad did his three-year family medicine residency and now works a monthly inpatient shift.

Vlad sat in the back of the car and held a small plastic trashcan next to Théo. As soon as we stopped, Vlad scooped Théo up. When I returned to the ER on foot from the parking lot, I found them in the small waiting area. Théo was still in his father’s arms, his limbs draped lifelessly, the perfect model for a child Pietà.

Once Théo was on his second bag of IV fluids and his cheeks had turned from grey-green to a dull pink, I realized — and said out loud — surprised and humbled that I had almost forgotten a date we usually commemorate with stiff drinks and hospital jokes: “It’s the three year anniversary of Théo’s heart surgery.”

Théo was one week old when he spent 13 hours in the operating theater with a South African cardiothoracic surgeon whose first name, Hillel, means “place of worship.” I was deeply comforted by this detail given that our son’s full name, Théodore, means “gift from God.” I believed that the two names, and as a consequence the surgeon and our child, were perfectly matched for a positive outcome. It was a clear sign.

Moreover, the surgeon’s last name, Laks, rhymed with the last name of the poetry professor, Peter Sacks (also a South African), whose lectures and writing workshops resuscitated my spirit during my cranky college years. Another obvious sign: the couplet of Laks and Sacks, the clear connection between the heart and the poetic line, the purveyors of beats that give us breath, life.

It will not surprise you that during my son’s hospital stay I dissected every shining detail I came across, and every shining detail proved full of meaning. These details became my religion and my religion kept me busy, sharp, on the borders of sane.

The surgery was two, three times as long as we had been promised. Dr. Laks put Théo on bypass twice — his coronary arteries were unusually placed and thus required unexpected tinkering — and the second time the operating team tried to take him off bypass, they had trouble starting his heart. At least that is what Vlad heard the nurse say to him when she called to give us an overdue update.

That phone call made my husband, nine months into his intern year in family medicine at the time, jump up and take action, any action he could. He wanted movement, agency in an impossible situation. He wanted to wait at the very door of the operating theater. He would have volunteered to go into the room if it had been allowed; in truth, he would have banged the door down. Instead, we drove to the hospital and paced outside her doors, in the open-air plaza with several water fountains and benches where patients, family members, and nurses sipped coffee and talked on cell phones.

We paced until the operating room nurse called again to say our son was out.

We rode the elevator to the third floor in silence. We rang the bell outside the cardiothoracic intensive care unit to request permission to enter. “Come in,” said the muffled voice and the man inside directed us to bed number seven. As we passed by the others, I noticed that Théo was the only baby, the only child, in a 12-bed unit of patients mostly over 70.

We introduced ourselves to Théo’s nurse with tense smiles and then walked towards him on tiptoe, afraid to speak or breathe. His infant hospital bed was small enough to make his “room” feel gigantic, like it could swallow us up. His eyes were closed and would continue to be for another week due to the sedation. His body was swollen and bruised, he had a monitor on his forehead to track his brain function, countless tubes and wires, and an open chest that would have to be coaxed together and sewn up, finally, five days later.

We agreed when the nurse offered to move the soft blanket covering Théo’s chest. We saw his fixed heart beating inside him, no larger than the size of his newborn fist, yellow-hued by the tint of the hospital plastic wrap that shielded his insides from the outside world. What we saw was more the movement of the heart than the heart itself, the pulsing up and down, the keeping going. I watched, mesmerized, and after a few moments I looked away and felt a throb in my gut, like I might be split in half.

Plastic wrap and all, I had not felt Théo closer to me in a long time. I had not yet sensed that the hospital might give him back soon, soon enough for me to stop being patient, to stop saying “we’ll see how he does and when we get to take him home.”

The fact that three years later Vlad and I sat on an ER bed with Théo as nurses triaged an ordinary stomach flu gone wrong was the strangest anniversary. We had him, but we had almost lost him. As we waited for Théo to finish the second bag of IV fluid and for the nurse to bring us the prescription for anti-nausea medication, Vlad and I looked at each other with the same two thoughts: how lucky we were to take him home (again), and the awful eventuality of another heart surgery to replace his leaky pulmonary valve, a sequel to his longer-than-expected newborn surgery.

3. “First Death in Nova Scotia” and “Travelling in the Family”

How does a dead child look? How do we look at him?

The closest I have come to these questions has been too close. For two weeks Théo’s eyes were sealed in deep sleep, one week before the surgery and one week after. For two weeks while he slept and did not move, I visited him for hours each day and night. I read and reread Goodnight Moon, I sang him our “Pickle Song,” I touched his head and his feet at the same time, which was the only way I could hold him. When he opened his eyes for the first time after two weeks, I was surprised by how dark they were and how intently he seemed to look at me.

Less than one year later, I saw Théo under sedation again, laid out on an exam table after a routine heart ultrasound (he will be followed by a cardiologist for the rest of his life though most ultrasounds will be unsedated). He looked beautiful, sweet, motionless — uncanny for our energetic boy who was learning to walk and nothing like the swollen and bruised baby we visited after heart surgery. Vlad and I took several photographs of him stretched out on the table with a bumble bee decorated muslin baby blanket covering him from the chest down, his surgery scar peeking out. We were giddy with nervousness and joy that he was not dead, just deeply asleep.

Théo will be put under sedation two more times this fall, for a catheter procedure and an MRI that will give his cardiologist better images of his pulmonary valve so that he can determine whether we need to replace it now, or whether we can wait. Maybe during the catheter procedure Théo, now three and half, will have stents inserted (is deployed a better word?) to relieve the narrowing of his coronary arteries. These will not be the last sedations, but for the first time Théo will talk to us when he wakes up. What will he say? Lately when we go to the doctor — for his younger brother’s vaccines, most recently — he says, “I don’t want to get fixed by the doctor.” I hear him and stop myself from making interpretations.

We have also seen our younger son Max sedated, only once, after his surgery at seven weeks old to release his Achilles tendons. He looked cherubic in his drug-induced sleep, and his new fiberglass casts to treat his clubfeet were perfectly white, almost haute couture. Max too was born with a defect, one far less dramatic and more easily treated. His foot surgery lasted less than an hour and was executed as planned. And even though Max’s nickname ends with “x” and his surgeon’s last name starts with “z,” the alphabetic proximity of their names did not leap into my mind as a shining detail that would get me through. I was simply confident that Dr. Zionts would be precise and gentle.

Théo and Max post-surgery and under heavy sedation, these are the moments when I have come the closest to seeing with my own eyes what a dead child might look like, what my dead child might look like, and I am grateful.

Elizabeth Bishop tells us what it is to see a dead child, from a child’s perspective, in “First Death in Nova Scotia.” This eerie and crushing poem was first published in the March 10, 1962, issue of The New Yorker. The poem comprises five stanzas, and the first line includes a comma that her editor Howard Moss proposed as an addition, to which Bishop agreed:

In the cold, cold parlor

my mother laid out Arthur

beneath the chromographs:

Edward, Prince of Wales,

with Princess Alexandra,

and King George with Queen Mary.

Below them on the table

stood a stuffed loon

shot and stuffed by Uncle

Arthur, Arthur’s father.

The poet’s mother takes her to see her two-month-old cousin in his coffin:

“Come,” said my mother,

“Come and say good-bye

to your little cousin Arthur.”

I was lifted up and given

one lily of the valley

to put in Arthur’s hand.

Arthur’s coffin was

a little frosted cake,

and the red-eyed loon eyed it

from his white frozen lake.Arthur was very small.

He was all white, like a doll

that hadn’t been painted yet.

Jack Frost had started to paint him

the way he always painted

the Maple Leaf (Forever).

He had just begun on his hair,

a few red strokes, and then

Jack Frost had dropped the brush

and left him white, forever.The gracious royal couples

were warm in red and ermine;

their feet were well wrapped up

in the ladies’ ermine trains.

They invited Arthur to be

the smallest page at court.

But how could Arthur go,

clutching his tiny lily,

with his eyes shut up so tight

and the roads deep in snow?

The final four lines are devastating: “But how could Arthur go…?” The child’s perspective is spot on, and one is frightened for her as her mother lifts her up to look inside the coffin. This is the only poem where Bishop’s mother appears in the flesh.

The title is a little strange too. “First Death in Nova Scotia.” Why “first”?

“First Death in Nova Scotia” is not an account of the first death Bishop experienced as a child. The first was the death of her father, who died in Worcester, Massachusetts, but she never wrote that poem. Instead, Bishop turned to translation. Indeed, for every four original poems Bishop published, she published one translation of a contemporary poet writing in Portuguese, Spanish, or French (she also published prose translations).

Bishop translated the major twentieth-century Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s “Travelling in the Family,” a poem where the poetic voice encounters “the shadow” of his dead father who takes him “by the hand,” but does not say anything to his son over the course of 12 stanzas. Seven of the stanzas end with the refrain, “But he didn’t say anything.” The speaker tries repeatedly to no avail, as we see in the ninth stanza:

Speak speak speak speak.

I pulled him by his coat

that was turning into clay.

By the hands, by the boots

I caught at his strict shadow

and the shadow released itself

with neither haste nor anger.

But he remained silent.

The poetic voice changes how he refers to his father, from “he” and “his” to addressing him directly with “you” and “yours,” in the tenth and eleventh stanzas. The two men connect through a “ghostly embrace”:

There were distinct silences

deep within his silence.

There was my deaf grandfather

hearing the painted birds

on the ceiling of the church;

my own lack of friends;

and your lack of kisses;

there were our difficult lives

and a great separation

in the little space of the room.The narrow space of life

crowds me up against you,

and in this ghostly embrace

it’s as if I were being burned

completely, with poignant love.

Only now do we know each other!

Eye-glasses, memories, portraits

flow in the river of blood.

Now the waters won’t let me

make out your distant face,

distant by seventy years…

Bishop underscores the shift from “his” to “your” as the translator. There is no indication in Drummond’s original poem, no quotation marks or italics or other marks, to make explicit the shift in the poetic voice from speaking of his father in the literary third person to speaking to him in the colloquial second person (the original uses the possessive pronoun “seu” in both cases, but Bishop knew that in Brazilian Portuguese, specifically in the dialects of the Southeast including Rio, São Paulo, and Drummond’s native Minas Gerais, “seu” refers to the second person in everyday speech).

In her translation Bishop clarifies what the original leaves ambiguous and up to interpretation. Her choice, which Drummond could have protested in their correspondence about her work, also hinges on English not having a similarly flexible possessive pronoun that can mean “your” or “his” depending on the context. Her choice makes clear that Drummond’s poetic voice succeeds in speaking to his father directly. Because of this shift in intimacy, the final stanza of the poem is all the more satisfying: “I felt that he pardoned me / but he didn’t say anything. / The waters covered his moustache, / the family, Itabira, all.”

“Travelling in the Family” first appeared in the June 1965 issue of Poetry and got top billing on the cover of the magazine. Bishop also included it in the 1969 edition of The Complete Poems and in the 1972 anthology she co-edited with Emanuel Brasil for Wesleyan University Press, An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Brazilian Poetry.

Bishop read the translation during a number of her own poetry readings, including the one on May 6, 1969, sponsored by the Academy of American Poets at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In his introduction, Robert Lowell called Bishop “the famous eye.” She read a few of her Brazilian poems, introducing each briefly: “Manuelzinho” was a true story; “The Armadillo” took place on St. John’s Day, the shortest day of the year in Brazil and the longest in the United States; and “House Guest” was set in Rio, but could have happened anywhere. She also noted that “Travelling in the Family” was about Drummond’s father. The poems had in common their “true” quality; they were all autobiographical in one way or other.

Bishop wrote to Drummond about her readings in her May 31, 1969, letter: “During the past year and a half, I have given six or seven public readings of poetry, most of them at universities, including Harvard and the University of California, and at all of them I have read my translation of your poem, “Viagem na família,” with a few explanatory remarks of my own.”

“Travelling in the Family” was significant to Bishop, significant enough for her to promote it as much as she did, and significant enough, in my mind, to function as an analog to the poem she never wrote about her father, which might have been called “First Death in Massachusetts,” where she too died on Lewis Warf in Boston in October 1979.

4. “Objects & Apparitions”

Bishop’s final book of poetry Geography III appeared three years before her death. The collection includes ten poems that delve into questions of memory and the passage of time. One translation appears in the sequence, the poem “Objects & Apparitions” by Octavio Paz, which is the only time Bishop included a translation among her original poems. (I wonder if her version of Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s “Travelling in the Family” might have been included in her collection Questions of Travel if she had translated it in time.)

Bishop’s final book of poetry Geography III appeared three years before her death. The collection includes ten poems that delve into questions of memory and the passage of time. One translation appears in the sequence, the poem “Objects & Apparitions” by Octavio Paz, which is the only time Bishop included a translation among her original poems. (I wonder if her version of Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s “Travelling in the Family” might have been included in her collection Questions of Travel if she had translated it in time.)

“Objects & Apparitions” appeared in The New Yorker in the June 24, 1974, issue, the only translation of hers to be published in the magazine, though the story might have been otherwise given editor Howard Moss’ encouragement and interest. In his January 31, 1969, letter he tells Bishop how much he liked her translation of Drummond’s poem “The Table,” which appeared in The New York Review of Books earlier that month: “I did have to tell you how beautiful the translation of [Drummond de] Andrade is. I love it. And if you have any others, please do send them my way[…] I hope Farrar, Straus is smart enough to bring out a book of the translations.”

Bishop writes back thanking him and asking if the magazine’s policy on translations has changed: “ARE YOU interested in translations? In the past, a few of mine, both prose and poetry, were rejected and The New Yorker wrote me then that they never published translations. However, since then I did see that very nice poem by Borges, so perhaps the magazine’s policy has changed?” Indeed it had.

Dedicated to Joseph Cornell, an artist both Bishop and Paz admired, “Objects & Apparitions” attests to the translation-ship the two poets developed in the 1970s when they each translated and published a handful of the other’s poems. They first met in 1971 at Harvard where they both taught the fall term. Bishop attended Paz’s lectures and socialized with him and his wife Marie José. In her letters, she writes of the Pazes fondly. In her July 9, 1975, letter to Frani Blough Muser she tells of visiting them in Mexico City and of recording a poetry roundtable for television: “We were 4 languages: Octavio, Joseph Brodsky, Vasko Popa (his language is Serbo-Croatian) & me [….] it was all very interesting and novel, to me, and went on for hours.”

Paz participated in Bishop’s memorial service in Cambridge, which was held on October 21, 1979, in Radcliffe Yard: “He spoke of the love for modern art he shared with Elizabeth, and then he read his Spanish poem on Joseph Cornell; Frank Bidart followed with Elizabeth’s English transmutation.”

A “transmutation” is what Paz liked to call translations, which he considered as creative as the composition of original work. The term transmutation is one that Paz borrowed from Roman Jakobson, a contemporary who taught at Harvard and MIT, but Paz redefined it for his discussion of poetry. For Paz, a transmutation transforms the original poem, which is what a translation should do.

Bishop’s “Objects & Apparitions” transforms the original in an unquestionable, structural way. As she was translating the poem, she proposed a change in the order of stanzas, which Paz agreed to and then corrected in the original Spanish. In his March 16, 1974, letter he praises her version:

Your translation is perfect. Nothing needs to be changed, absolutely nothing. It is not only faithful, but rather at times better than the original. For example, I write — translating literally, “platement”, from French — “hacer un cuadro como se hace un crimen [“to do a painting like one does a crime”] but you say “to commit a painting the way one commits a crime.” Magnificent! I don’t know what I would give to have written that “to commit a painting.” I love it the way I love Thumbelina lost in her gardens of light. Yes, you are very right — how did I miss it? — stanza 10 should be stanza 13, the penultimate one. I have already made the change and will write to Dore Ashton [the art critic and editor of A Joseph Cornell Album] to make the correction. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Bishop’s suggested change in stanza order strengthens the poem’s closing by providing a two-stanza-long meditation on poetic language in the context of visual art, more specifically Paz’s poetry in the framework provided by Cornell’s boxes:

The apparitions are manifest,

their bodies weigh less than light,

lasting as long as this phrase lasts.Joseph Cornell: inside your boxes

my words became visible for a moment.

The sequence of stanzas highlights a paradoxical message. The final line of stanza 13 says the apparitions last “as long as this phrase lasts,” which literally means as long as the phrase takes to read and suggests a mere instant, but also points to permanence in the way Shakespeare and others teach us that language fashioned into art is immortal. The final line moves into the past tense to emphasize that the phrase mentioned in the previous stanza did not last: the poetic voice’s words and lines “became,” and were, “visible” for a moment. And yet every time we read and reread the poem, the phrase endures once again.

The momentary visibility of Paz’s words inside Cornell’s boxes recalls the poem’s second stanza — “Monuments to every moment, / refuse of every moment, used: / cages for infinity” — as well as Bishop’s early poem “The Monument” (after Max Ernst’s frottages) with its artifact that seeks “to cherish something” and to “commemorate.” Again, the paradox: how can we make a monument to every single moment? And how can we possibly cage infinity? It makes no sense, though we try. The act of commemorating or cherishing or remembering cannot be continuous — if it were, it would be called “knowing.”

I know I will never forget certain anniversaries. The day my grandfather Don Hernán was born, which happens to be Vlad’s birthday. The day Théo had heart surgery, his almost death day that became his second birthday (and, by extension, I will always remember André Breton’s two birthdays, the second one chosen by him because of its more auspicious astrological coordinates). I will never forget the morning of Max’s surgery, the day I turned 33. And I will never, never forget the day Théo was taken from us, the day we found out something was terribly wrong with his heart, the day I expected to take him home.

5. I Lost My Mother’s Watch – March 6, 2008

“Let them do whatever tests they need. He’s fine.” I squeezed two-day-old Théo a little tighter against me and he mewed.

A few hours later the ultrasound technician named David took images of Théo’s heart with a small probe for newborns. Théo didn’t squirm during the echo. I held his arms down and Vlad paced behind me. I wanted it to end so I could feed him.

After, I sat with Théo in my arms and Vlad next to me. Vlad took photos of Théo, who still had EKG stickers on his chest. Théo looked into my eyes and started to fall asleep with a smile. He had just taken milk.

There was a knock at the door and three women walked in, our nurse and two doctors. At the same moment Vlad’s cell phone rang and our pediatrician told him that Théo had a problem, would need surgery. Vlad started to cry and handed the phone to me.

“We have to take your baby,” the head of the neonatal intensive care unit said. And she took him.

I don’t know how I handed him over.

I don’t know why I didn’t collapse, how I kept myself from screaming and pounding the walls and throwing everything at the windows of the room, to break every inch of glass, to break all of us out of there.

What I do know sounds like a digression, a distraction to keep myself going. It’s not.

What I do know is how sneaky Elizabeth Bishop can be.

Her poems first read like quiet and picturesque memoranda on the curious details of everyday life. Oh, but how she can be sly. In her villanelle “One Art” she repeats throughout that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master” – yet there is one line I did not understand until Théo was taken from me.

In the tenth line, smack at the middle of nineteen lines on the art of losing, Bishop says: “I lost my mother’s watch.” She has already talked of losing keys, names, places one meant to visit, the wasted hour, and she will speak, in the second half of the poem, of losing houses, cities, rivers, and ultimately “you.”

I had never understood why her mother’s timepiece, a ticking mechanism held to her wrist, would anchor the poem. I had never understood that her mother’s watch also referred to her gaze, her presence, her watchful eye. Bishop lost her mother’s watch when she was a young child; her father died when she was an infant and by the time the poet was five years old her mother was sent to a mental hospital.

“I lost my mother’s watch,” screamed Théo without words but with flailing limbs as the transport team prepared to move him to the bigger hospital a few miles away. They put his arms and legs in restraints in order to “stabilize” him.

“I lost my mother’s watch,” he screamed as I packed my hospital bag with son-empty hands.

Image credit: Amy Bernier/Flickr