The dispute between Himalayan mountaineers and writers Greg Mortenson and Jon Krakauer has been cast as a dispute between fact and fiction. Recently, Mortenson’s wildly popular book from 2006, Three Cups of Tea—which narrates his failed attempt to climb K2, his kidnapping by the Taliban, and his early efforts to build schools for Pakistani children—was debunked by Krakauer in Three Cups of Deceit. As you may know, this 89-page document systematically exposes Mortenson’s story as “an intricately wrought work of fiction presented as fact” and insists that both Mortenson’s “books and his public statements are permeated with falsehoods.” Though his publisher has launched in investigation into the book’s claims, Mortenson has insisted on its veracity.

The dispute between Himalayan mountaineers and writers Greg Mortenson and Jon Krakauer has been cast as a dispute between fact and fiction. Recently, Mortenson’s wildly popular book from 2006, Three Cups of Tea—which narrates his failed attempt to climb K2, his kidnapping by the Taliban, and his early efforts to build schools for Pakistani children—was debunked by Krakauer in Three Cups of Deceit. As you may know, this 89-page document systematically exposes Mortenson’s story as “an intricately wrought work of fiction presented as fact” and insists that both Mortenson’s “books and his public statements are permeated with falsehoods.” Though his publisher has launched in investigation into the book’s claims, Mortenson has insisted on its veracity.

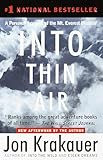

Despite the antithetical roles they have assumed in this drama, Mortenson and Krakauer have much in common. Like Mortenson, Krakauer has parlayed his mountaineering adventures in exotic locales into a successful writing career. Into Thin Air, his gripping nonfiction account of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, popularized and epitomized a genre that has in many ways become synonymous with Krakauer: the true-life extreme survival story. Stories in this genre follow a predictable pattern: an individual sets out on an adventure, things go horribly wrong, he or she confronts the possibility death, and lives to tell an incredible story. Disaster pushes man to the edge between life and death, and a lucky few live to tell about it. This plotline rarely changes; the details are grisly, the scenarios harrowing. Yet we can’t get enough of such extreme survival stories.

Despite the antithetical roles they have assumed in this drama, Mortenson and Krakauer have much in common. Like Mortenson, Krakauer has parlayed his mountaineering adventures in exotic locales into a successful writing career. Into Thin Air, his gripping nonfiction account of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, popularized and epitomized a genre that has in many ways become synonymous with Krakauer: the true-life extreme survival story. Stories in this genre follow a predictable pattern: an individual sets out on an adventure, things go horribly wrong, he or she confronts the possibility death, and lives to tell an incredible story. Disaster pushes man to the edge between life and death, and a lucky few live to tell about it. This plotline rarely changes; the details are grisly, the scenarios harrowing. Yet we can’t get enough of such extreme survival stories.

Take, for instance, Lauren Hillenbrand’s latest nonfiction bestseller Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption, which relates Louis Zamperini’s improbable true adventures, from shipwreck and starvation to shark attacks and torture. Zamperini’s extreme story is filtered through Hillenbrand’s capable narration, but it has much in common with other first-person survival accounts, including Aron Ralston’s 2005 book, Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Ralston’s book chronicles his amputation of his own arm following a bouldering accident in a Utah canyon, and was adapted into a successful Hollywood movie (127 Hours) starring James Franco, who was nominated for an Oscar for the role. In 1974, Piers Paul Read published Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, which charted the grim ordeal of a South American rugby team after their plane crashed in the Andes mountains and they resorted to survival cannibalism in order to stay alive.

Take, for instance, Lauren Hillenbrand’s latest nonfiction bestseller Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption, which relates Louis Zamperini’s improbable true adventures, from shipwreck and starvation to shark attacks and torture. Zamperini’s extreme story is filtered through Hillenbrand’s capable narration, but it has much in common with other first-person survival accounts, including Aron Ralston’s 2005 book, Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Ralston’s book chronicles his amputation of his own arm following a bouldering accident in a Utah canyon, and was adapted into a successful Hollywood movie (127 Hours) starring James Franco, who was nominated for an Oscar for the role. In 1974, Piers Paul Read published Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, which charted the grim ordeal of a South American rugby team after their plane crashed in the Andes mountains and they resorted to survival cannibalism in order to stay alive.

Why are we so fixated with such tales, gory and clichéd as they may be? The very gruesomeness of the material is an undeniable source of fascination. Yet our national obsession with extreme survival tales stems not only from their content but the fact that they are true. Ours is a digital age of “truthiness” in which so-called reality TV is scripted and the extreme situations that Bear Grylls undergoes on his TV show Man vs. Wild are revealed to have been surprisingly comfortable. As opposed to works of fiction, true-life extreme survival stories are granted a special type of immunity and cultural authority. How do you critique the truth? The difficulty of doing so makes the marketing of nonfiction under the banner of truth even more irresistible for publishers and authors.

But strangely, what makes the true-life extreme survival story so appealing is its fictional quality. Self-amputation, hypoxia at high altitudes, shark attacks, cannibalism: this is the stuff of fantasy. As the New York Times writes of Unbroken, “some of it sounds too much like pulp fiction to be true.” Reviews of Into Thin Air insist that it “reads like a fine novel” and admit that “though it comes from the genre named for what it isn’t (nonfiction), this has the feel of literature.” “Every once in a while,” another notes, “a work of nonfiction comes a long that is as good as anything a novelist could make up.”

While the unbelievable qualities of nonfiction survival stories prompt the comparison to fiction, the book that’s generally considered the first novel written in English used truth as a marketing device to legitimate the new form of the novel. And it also happens to be an extreme survival story. In Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the shipwrecked Crusoe survives alone on an island for 28 years by planting crops, taming wild animals, and enduring battles with cannibals and pirates. In various advertisements and promotional prefaces, Defoe markets his fictional novel as an incredible true-life story. The preface to the first volume reads: “the Editor believes the thing to be a just History of Fact; neither is there any Appearance of Fiction in it.” In prefaces to later volumes, Defoe (speaking in the voice of the fictional Crusoe) again insists that these are “real facts in my history.” Apparently, some eighteenth-century readers believed this claim. According to Theophilus Cibber, a writer contemporary of Defoe’s, the novel was filled with so many “probable incidents” that “it was judged by most people to be a true story.” Defoe capitalized upon this ambiguity, writing two more sequels to the Crusoe story after the phenomenal success of the first edition. A century later in 1822, Charles Lamb, in a letter to Walter Wilson, describes the technique (which the scholar Ian Watt later called “formal realism”) that helped make Defoe’s novel such a hit: “Facts are repeated over and over in varying phrases till you cannot chuse but believe them. It is like reading evidence in a court of Justice.” The effect, Lamb describes, is one of the truth and nothing but the truth.

While the unbelievable qualities of nonfiction survival stories prompt the comparison to fiction, the book that’s generally considered the first novel written in English used truth as a marketing device to legitimate the new form of the novel. And it also happens to be an extreme survival story. In Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the shipwrecked Crusoe survives alone on an island for 28 years by planting crops, taming wild animals, and enduring battles with cannibals and pirates. In various advertisements and promotional prefaces, Defoe markets his fictional novel as an incredible true-life story. The preface to the first volume reads: “the Editor believes the thing to be a just History of Fact; neither is there any Appearance of Fiction in it.” In prefaces to later volumes, Defoe (speaking in the voice of the fictional Crusoe) again insists that these are “real facts in my history.” Apparently, some eighteenth-century readers believed this claim. According to Theophilus Cibber, a writer contemporary of Defoe’s, the novel was filled with so many “probable incidents” that “it was judged by most people to be a true story.” Defoe capitalized upon this ambiguity, writing two more sequels to the Crusoe story after the phenomenal success of the first edition. A century later in 1822, Charles Lamb, in a letter to Walter Wilson, describes the technique (which the scholar Ian Watt later called “formal realism”) that helped make Defoe’s novel such a hit: “Facts are repeated over and over in varying phrases till you cannot chuse but believe them. It is like reading evidence in a court of Justice.” The effect, Lamb describes, is one of the truth and nothing but the truth.

Defoe probably based his novel on the real-life story of Alexander Selkirk, an eighteenth-century sailor who survived for four years alone on an island before being rescued. Jonathan Franzen recently visited this South Pacific island (now named, appropriately, Alexander Selkirk) to experience his own Crusovian adventure, which involved re-reading Defoe’s novel on the island. According to Franzen, one of the most interesting questions associated with the origins of the English novel is this: “should a strange story be accepted as true because it is strange, or should its strangeness be taken as proof that it is false?” The genre of extreme survival stories, which, by definition, deals in the strange, sensational, and unbelievable, makes this question even more problematic and acute—and subject to exploitation by savvy writers.

Over one hundred years after the publication of Crusoe’s novel and on the other side of the Atlantic, Edgar Allan Poe published his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, and marketed it as a true story. Published in 1838, Arthur Pym was hailed as the American Robinson Crusoe, and, not surprisingly, it has much in common with Crusoe, including a bizarre plotline, “atrocious butchery,” and an insistence on authenticity. In one of his essays, Poe himself marveled at Defoe’s literary achievement, which lay in the fact that it did not seem like one at all: “Men do not look upon it in the light of a literary performance. Defoe has none of their thoughts—Robinson all.” What Poe admires here is Defoe’s sleight-of-hand, and he appeared to want to emulate it. Poe’s own work of extreme survival fiction pretended to be Pym’s first-person account of his strange seafaring adventures. For some commentators, Poe’s hybrid work reconciled generic opposites: according to the August 1, 1838 edition of Horace Greeley’s New Yorker newspaper, “it is a work more marvelous than the wildest fiction, yet is presented and supported as sober truth.” But for other readers, Poe was just a liar. Reviewers criticized the book as implausible and fabricated. One review admired the story as a work of fiction, but condemned its being “palmed upon the public as a true thing.” William Burton, the editor of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, huffed that it was “an impudent attempt at humbugging the public” and that Poe “puts forth a series of travels outraging possibility, and coolly requires his insulted readers to believe his account.”

Over one hundred years after the publication of Crusoe’s novel and on the other side of the Atlantic, Edgar Allan Poe published his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, and marketed it as a true story. Published in 1838, Arthur Pym was hailed as the American Robinson Crusoe, and, not surprisingly, it has much in common with Crusoe, including a bizarre plotline, “atrocious butchery,” and an insistence on authenticity. In one of his essays, Poe himself marveled at Defoe’s literary achievement, which lay in the fact that it did not seem like one at all: “Men do not look upon it in the light of a literary performance. Defoe has none of their thoughts—Robinson all.” What Poe admires here is Defoe’s sleight-of-hand, and he appeared to want to emulate it. Poe’s own work of extreme survival fiction pretended to be Pym’s first-person account of his strange seafaring adventures. For some commentators, Poe’s hybrid work reconciled generic opposites: according to the August 1, 1838 edition of Horace Greeley’s New Yorker newspaper, “it is a work more marvelous than the wildest fiction, yet is presented and supported as sober truth.” But for other readers, Poe was just a liar. Reviewers criticized the book as implausible and fabricated. One review admired the story as a work of fiction, but condemned its being “palmed upon the public as a true thing.” William Burton, the editor of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, huffed that it was “an impudent attempt at humbugging the public” and that Poe “puts forth a series of travels outraging possibility, and coolly requires his insulted readers to believe his account.”

In terms of what is at stake, the Mortenson scandal may have little in common with Daniel Defoe’s or Edgar Allan Poe’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century manipulations of the public and the press. Mortenson’s book was required reading for the U.S. military and is the basis upon which his entire humanitarian organization was founded. If Krakauer’s claims are validated, then Mortenson could be said to have done more than insult and humbug his readers. But then again, the market for extreme survival stories, from the eighteenth century to today, has always been driven by—and eager to exploit—the same wish: the impossible desire for truth that possesses the flair of fiction and fiction legitimated by the veracity of truth.

Image credit: Pexels/Francesco Ungaro.