The 10th Tribeca Film Festival, which ended May 1, was a richly musical affair. It featured movies about Kings of Leon, A Tribe Called Quest, Ozzy Osbourne, Miriam Makeba, the irrepressible Haitian band Septentrional, the Academy Award-winning songwriters Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova, and a new Cameron Crowe documentary about Elton John and Leon Russell. Nearly lost in this pleasing din were two quiet movies, a feature and a documentary, that grew, respectively, out of a work of literature and the misguided urge to lionize writers.

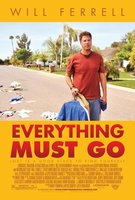

Will Ferrell Channels Raymond Carver

Everything Must Go, the writing and directing debut of Dan Rush, is adapted from a Raymond Carver short story called “Why Don’t You Dance?” Rush makes two crucial creative decisions, one necessary, one risky. First, he fleshes out Carver’s bare-bones story, which was little more than a sketch after it was edited – some would say butchered – by Gordon Lish’s heavy blue pencil. Then Rush makes a daring and, as it turns out, inspired casting choice: He puts ham-fisted funnyman Will Ferrell (Old School, Anchorman, Talladega Nights, etc.) in the dark lead role of Nick Halsey, a super-salesman who just got sacked from his job because of his drinking. As the movie opens, Nick is sitting in his parked car, gulping down a flask of whiskey while chanting salesman mantras and fuming over the indignity of his firing. His troubles haven’t begun. After stopping for a couple of 12-packs of beer, he returns to his home in a nameless Arizona suburb to find his possessions scattered across his front yard, the locks changed, his bank account frozen, his wife gone. A cop buddy from A.A. stops by with a three-day permit for a yard sale. That’s how long Nick has to get his act together, or fall into the blackest of holes. The narrative time bomb has begun ticking.

Everything Must Go, the writing and directing debut of Dan Rush, is adapted from a Raymond Carver short story called “Why Don’t You Dance?” Rush makes two crucial creative decisions, one necessary, one risky. First, he fleshes out Carver’s bare-bones story, which was little more than a sketch after it was edited – some would say butchered – by Gordon Lish’s heavy blue pencil. Then Rush makes a daring and, as it turns out, inspired casting choice: He puts ham-fisted funnyman Will Ferrell (Old School, Anchorman, Talladega Nights, etc.) in the dark lead role of Nick Halsey, a super-salesman who just got sacked from his job because of his drinking. As the movie opens, Nick is sitting in his parked car, gulping down a flask of whiskey while chanting salesman mantras and fuming over the indignity of his firing. His troubles haven’t begun. After stopping for a couple of 12-packs of beer, he returns to his home in a nameless Arizona suburb to find his possessions scattered across his front yard, the locks changed, his bank account frozen, his wife gone. A cop buddy from A.A. stops by with a three-day permit for a yard sale. That’s how long Nick has to get his act together, or fall into the blackest of holes. The narrative time bomb has begun ticking.

Rush wisely ignores the ticking and sets a leisurely pace, lets the camera linger, lets his actors build emotional momentum slowly, quietly. This is important to a Carver story, as Marilynne Robinson noted back in 1988: “His impulse to simplify is like an attempt to create a hush, not to hear less, but to hear better.”

And that’s what this movie comes down to – Nick’s process of learning how to hear, and see, better. Ferrell is outstanding as the wounded soul who can’t hear or see anything at the outset – until he meets Rush’s most inspired addition to Carver’s original cast, Kenny (Christopher Jordan Wallace), a chubby kid with demons of his own who becomes Nick’s unlikely ally, his teacher in the art of saving himself. Another addition is a pregnant neighbor named Samantha (Rebecca Hall), who is moving in across the street and will become the valve that allows Nick to empty the poison from his soul.

It works beautifully because Ferrell conveys an almost impossible stew of emotions – rage, self-pity, insecurity and a dry sense of humor that never comes close to turning hammy. What a pleasant pair of surprises: there’s a new director worth watching, and Will Ferrell can actually act.

The Creepy World of Mrs. Neal Cassady

The documentary Love Always, Carolyn has the (unintended?) virtue of showing us just how creepy literary hagiography can get. Directed by first-timers Maria Ramstrom and Malin Korkeasalo, it opens with its subject, Carolyn Cassady, telling the filmmakers, “I’m not known as a writer. The only reason anyone is interested in me is because I was married to Neal Cassady and was a lover of Jack Kerouac. No one has ever cared about anything else. Even you – so far.” It gets darker. “I wish I could stop talking about it,” Carolyn continues. “I have to keep saying the same things over and over. So it’s very tiresome.” And darker. “In a secret way I kind of dig the attention. So it’s, you know, a conflict.”

We learn other things about conflicted Carolyn Cassady, who is now an old lady with a crinkly, sour face. We learn that she wrote a book called Off the Road: My Years With Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg – “to set the record straight and not be bothered,” she claims. We learn that she’s still pissed off that she didn’t get a dime of royalties for the iconic photograph she took of Jack and Neal that graces the cover of Neal’s unfinished autobiography, The First Third. We learn that Neal frequently left her at home to raise their three children while he ricocheted around the country, to Tangier and Mexico City and back, fucking anything that walked upright, male or female, eventually abandoning his booze-marinated buddy Kerouac in favor of Ken Kesey and his acidophilic Merry Pranksters, tripping with them until he collapsed on some railroad tracks in Mexico and died at the age of 41. As Carolyn dryly notes, “He didn’t quite get the marriage thing together.”

We learn other things about conflicted Carolyn Cassady, who is now an old lady with a crinkly, sour face. We learn that she wrote a book called Off the Road: My Years With Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg – “to set the record straight and not be bothered,” she claims. We learn that she’s still pissed off that she didn’t get a dime of royalties for the iconic photograph she took of Jack and Neal that graces the cover of Neal’s unfinished autobiography, The First Third. We learn that Neal frequently left her at home to raise their three children while he ricocheted around the country, to Tangier and Mexico City and back, fucking anything that walked upright, male or female, eventually abandoning his booze-marinated buddy Kerouac in favor of Ken Kesey and his acidophilic Merry Pranksters, tripping with them until he collapsed on some railroad tracks in Mexico and died at the age of 41. As Carolyn dryly notes, “He didn’t quite get the marriage thing together.”

Their son John, who is obviously damaged goods, says, “I was, like, Neal’s fan rather than his kid.” Yet John Cassady soldiers on, giving talks at the Beat Museum in San Francisco, introducing his mother at readings, exploring potential new revenue streams such as a beverage called “Cassady Wine” that comes in a jug with a handle to make it look like authentic hobo rotgut.

Sitting through this creepy movie was the longest 70 minutes I’ve spent outside a jail cell, and it reminded me of the recent William S. Burroughs documentary, A Man Within, which I wrote about here last year. They’re both part of the tsunami of beat documentaries, biographies, critical studies, feature films, magazine articles, memoirs, websites and blogs that just keeps rolling along. I said it last year, but after watching Love Always, Carolyn I’ll say it again: Will you Beat hagiographers please be quiet, please?