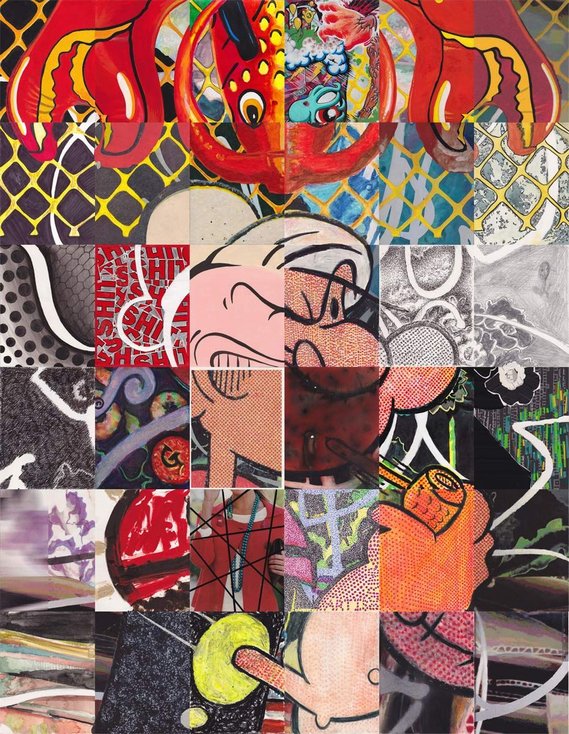

The Drawing Center in New York recently mounted a show called “Day Job” that neatly upended the timeless lament of every struggling writer, artist and musician – My day job is robbing me of the time to do my REAL work! In a clever, counter-intuitive twist, the curator of the show asked a dozen artists to produce a work that illustrated how their day jobs enrich their art. There were intriguing contributions from artists who pay the rent by working as a landscape architect, a medical illustrator, a set designer, an art installer, a museum guard. One work in particular jumped out at me. It was a collage called “Substantially Similar? (after Koons 2010),” [above] composed of 36 rectangular panels, each contributed by a different artist and then assembled by the artist who conceived the piece, Alfred Steiner. The result was an instantly recognizable riff on Jeff Koons’s “Popeye” series – an appropriation from an appropriator who has made headlines in several highly publicized copyright cases. A note beside “Substantially Similar?” left no doubt about its creator’s stance on the passionate arguments for and against copyright laws: “By engaging these issues, the project may also suggest how copyright antagonizes artistic freedom while providing artists no discernible benefit.”

Alfred Steiner is a 37-year-old Ohio native who grew up believing he was going to be an artist, then wound up attending Harvard Law School. Today he paints, draws and produces conceptual pieces – when he isn’t practicing copyright law for a large Manhattan law firm. We sat down together at a cafe near his home recently and talked about how copyright law – for better and for worse – affects the books, art, music and journalism of Jonathan Lethem, Jeff Koons, Jay-Z, the New York Times and the Pittsburgh mash-up D.J. Gregg Gillis, better known as Girl Talk.

The Millions: I was wondering how to describe you to our readers. Is this guy a copyright lawyer who happens to be an artist, or is he an artist who happens to be a copyright lawyer? Or both? Or neither?

Alfred Steiner: I spend the majority of my time on the art part. But the law is an important part of my life, and it’s certainly how I make a living. But I view the art as what I’m most interested in doing.

TM: So you’re an artist who happens to be a copyright lawyer.

AS: Yeah, if I had to choose.

TM: Let’s start with your piece at the Drawing Center. Where did the idea come from?

AS: Well, there was a call from the Drawing Center for proposals about how your day job related to your work. It could be antagonistic, it could be complimentary. So I was thinking about how my artwork relates to my day job, and how I might raise certain issues related to intellectual-property law and copyright law.

TM: So you commissioned other artists to do pieces of the work? Tell me about that.

AS: Essentially, I wanted to select a work that fulfilled a number of criteria. One of which was, when it was broken into many pieces, few if any of the pieces would be recognizable. And I wanted to pick a work by somebody that would have some significance in terms of contemporary art and copyright, which is why I selected Jeff Koons. He’s used all sorts of things – Odie from “Garfield,” the Pink Panther – and in this case he was using Popeye. While I was working on this, I learned that Popeye is no longer under copyright in Europe, but he is the United States for a few more years. Which is another interesting twist that was serendipitous.

TM: So you got different artists to contribute patches, which you patched together?

AS: Right. I took an electronic version of the Koons original and divided it up into 36 pieces and sent each artist just one little piece, via e-mail, so they wouldn’t recognize the whole thing. I gave them instructions on how to create an image based on the image that I’d e-mailed them. The only other instructions were a very close paraphrase of the 2nd Circuit’s test for copyright infringement – which is, “would a reasonable person regard the two works’ esthetic impact as the same?”

TM: In other words, would a layman recognize these two works as being the same thing?

AS: Right.

TM: So the contributors didn’t know what they were reproducing?

AS: Right.

TM: And the result was a piece that looked vaguely like Koons, but was different.

AS: It had the essence of the original but was clearly a new work.

TM: In your note at the show you mentioned that copyright antagonizes artistic freedom while providing artists no discernible benefit. Tell me what you mean by that.

AS: Well, the point is that as an artist your livelihood, in general, depends on your sale of unique objects, or small editions of objects. So copyright is not as important to you as it is to a musical artist…

TM: Or a writer.

AS: Exactly. Because contemporary artists don’t sell millions of copies. The fact is in the art world when one artist copies another artist, it only helps the artist being copied because the more people who imitate you or are influenced by you – the more that happens, the more it shows you’re part of the ongoing story.

TM: Let’s talk about writers. In his essay in Harper’s, “The Ecstasy of Influence,” Jonathan Lethem wrote that copyright isn’t a right but a “government-granted monopoly on the use of creative results.” Would you agree with that?

AS: Yes, I would agree with that. The Constitution allows Congress to protect the works of authors for limited periods of time in order to promote creative work.

TM: But Lethem’s point is that the Founders thought works should be protected a short amount of time, maybe 14 years or so. Now it’s the lifetime of the author, plus 70 years. He thinks that’s a terrible idea for writers, and for writing, and for books. Do you agree?

AS: My sense is that life plus 70 years is too long. It doesn’t need to be that long to fulfill the purpose. You could argue that one interesting analog is fashion. There’s no intellectual-property protection for fashion, but I don’t think anyone would argue that fashion lacks for innovation. So, do we really need to protect the author for his entire lifetime plus 70 years to encourage innovation? I don’t think so.

TM: You know, William Gibson has this famous quote – “All information wants to be free.” It’s a good sound bite, but is it true?

AS: Well, for me there are two strains to that. One is that information is inherently hard to contain, but people are curious, they want information, they historically have wanted to know the truth, not necessarily with a capital T. So when you try to control information, you’re running an uphill battle.

TM: Now we’re talking about WikiLeaks. But getting back to books – information might want to be free, but if you flip that over, don’t people who write books and create works of art have a certain right to be remunerated for their creative effort?

AS: I think there’s a scale. Let’s say all 50 states had different copyright laws. You could imagine a state where it was extremely restrictive and you couldn’t copy anything. What would the products of that state look like compared to a state that was laissez faire and you could do whatever you want? To me that’s an interesting question: where should the bar be set? I think you’d have enforcement problems in the very strict state. And if you had very powerful media players who controlled everything, you wouldn’t have YouTube with the millions of things that are on there, many or most of which are probably infringing someone’s copyright. You would have fewer viewpoints expressed, and I think that’s detrimental. The more things that get created, the more viewpoints and opinions will be expressed, and that’s better for a democracy.

TM: You’re talking not just about graphic art, but about writing, music.

AS: I’m talking about all creative endeavors but I was thinking primarily about writing.

TM: Where do you think copyright is going in America right now? Is it becoming more porous, more loose, more free? Or is it going in the opposite direction? I’m thinking about the $125 million Google settlement, paying authors for the right to digitize their books.

AS: The Google settlement is an interesting case because they think if a project is interesting, they’ll go ahead and do it even if there are intellectual-property problems – then deal with those later. But I think information is becoming much easier to distribute and, as a result of that, copyright laws are tightening in a sense, to try to deal with that ease of distribution and allow creators to recoup the investment they make in producing this stuff. This becomes even more important when you’re creating, say, an encyclopedia, something that requires the collective effort of lots of people, and a lot of coordination, and a big budget to produce. Those things will never be produced if somebody can immediately make a million copies and not have to pay whoever produced it. That applies even more so in the context of film, where you have budgets routinely north of a hundred million dollars. Who’s going to invest in that if everybody can download a copy with no fear of prosecution?

TM: Did you happen to see that essay I wrote for The Millions about Jonathan Lethem’s Harper’s essay and David Shields’s Reality Hunger and the Jay-Z book?

AS: Yeah, “Jay-Z is not a Proudhon of Hip-Hop.” (laughs)

TM: In that essay, I mentioned the young German writer Helene Hegemann, who copied passages of her novel, Axolotl Roadkill, from other sources – websites, other novels – and a lot of people in Germany said, “That’s okay. It’s a novel about Berlin club kids, that’s the culture it’s about, and it’s an expression of that culture.” She was up for a big literary prize and they let her continue to compete for the prize even after the plagiarism became known. I thought that was a little bit shocking – for people to say that since it’s a novel about people sampling in clubs in Berlin, then the writer has the right to sample from other writers and that’s a legitimate form of artistic expression. I think that’s stretching it.

AS: I tend to agree with you. Just because you’re writing about how people are sampling, or taking from other sources, that doesn’t allow you to plagiarize or copy without providing either attribution or some sort of remuneration. It depends. If she’s taking a sentence here or there from hundreds of different places, that’s one thing. The other thing I would say – and this is the tougher question – if she’s copying a couple of pages here or there, in the context of a 400-page novel, that’s not that much. And if what she has created with this novel is startlingly new or interesting, I think it would be sad to say she can’t distribute this thing that is great and that everybody would benefit from. One other thing I would mention in that context – have you ever heard of Girl Talk?

TM: Sure, the D.J. from Pittsburgh.

AS: He’ll make songs that are totally based on samples. One song may have 200 samples, so many that there’s no way you could pay each artist. He’s very well received critically. The question is, should it be possible to make that kind of work or not? I kind of think, yes, it should be possible.

TM: What Girl Talk is doing is very similar, to me, to what William S. Burroughs did – and that’s very different from what Helene Hegemann did. Burroughs said, “I’m going to take a pair of scissors and cut up hundreds of books and newspapers and magazines, then scramble it around and put it back together to recreate a certain state of mind.” That was his “cut-up” technique – and that’s very much what Girl Talk is doing. They both say, “This is our intent and this is our method.” And it’s transparent. When someone takes a huge passage from someone else’s book and then says, “That’s what I was trying to do,” I say that’s bullshit.

AS: I tend to agree with you. If you go to my website and look at my works, when I borrow something it’s obvious, it’s transparent. I have these drawings that are based on characters from The Simpsons. They’re not merely copies, but anybody who’s familiar with American pop culture will recognize where they’re from. I’m not trying to hide it. Or if I’m basing something on a work by another artist, I’ll say “after Koons.” Going back to that novelist in Germany, if she’s got footnotes and everything’s attributed to whomever it came from, then I think it’s a lot harder to criticize her for it.

TM: I would go with that, but there were no footnotes. I’m not against people using other people’s things; I’m against them not admitting that they’re using them and then saying, as Hegemann said, that “there’s no such thing as originality, there’s only authenticity.”

AS: I agree. I think you and I are on the same page on this. If you challenge most people about their beliefs on this, I think you’ll get them to agree that there needs to be some way for people to get paid and to have confidence that other people are not going to be out there using their work in a way that harms their financial interest.

TM: To sum up, do you think that protection is going to be around forever? Let’s face it, the way things are changing right now with the digitization of so much information – entire libraries – it’s an unknown where we’re going. Where do you think it’s heading?

AS: There’s actually a book by a colleague of mine named Paul Goldstein, and its task is to make that prediction. I think copyright protection is likely to continue indefinitely, and I think it will become even more important in a world that becomes increasingly intangible, where people’s lives are less about walking down the street getting hit by a rock and more about watching a screen or looking at their Twitter feed. That stuff is going to become more and more valuable and there’s going to be more and more spent to protect it. And technology is going to be very important here. Most consumers are going to be at a point where it’s cheap enough and it just makes life easier to pay the toll that media people put there.

AS: There’s actually a book by a colleague of mine named Paul Goldstein, and its task is to make that prediction. I think copyright protection is likely to continue indefinitely, and I think it will become even more important in a world that becomes increasingly intangible, where people’s lives are less about walking down the street getting hit by a rock and more about watching a screen or looking at their Twitter feed. That stuff is going to become more and more valuable and there’s going to be more and more spent to protect it. And technology is going to be very important here. Most consumers are going to be at a point where it’s cheap enough and it just makes life easier to pay the toll that media people put there.

TM: Speaking of tolls, the New York Times just announced that it’s going to start charging for its web content, but it’ll be free for print subscribers. Do you think people will pay the toll?

AS: In that case, maybe no. With news, people just want news, and the source doesn’t tend to matter. People may just go to Google News and get it for free. With music and literature, the source is much more important. If you want to read a James Patterson novel, you’re not going to download Moby-Dick just because it’s free. And there are always going to be people who steal, who don’t mind the possibility that they’re going to get a virus from downloading some file. I think it’s going to be a race between these pirates and the people trying to control it.