1.

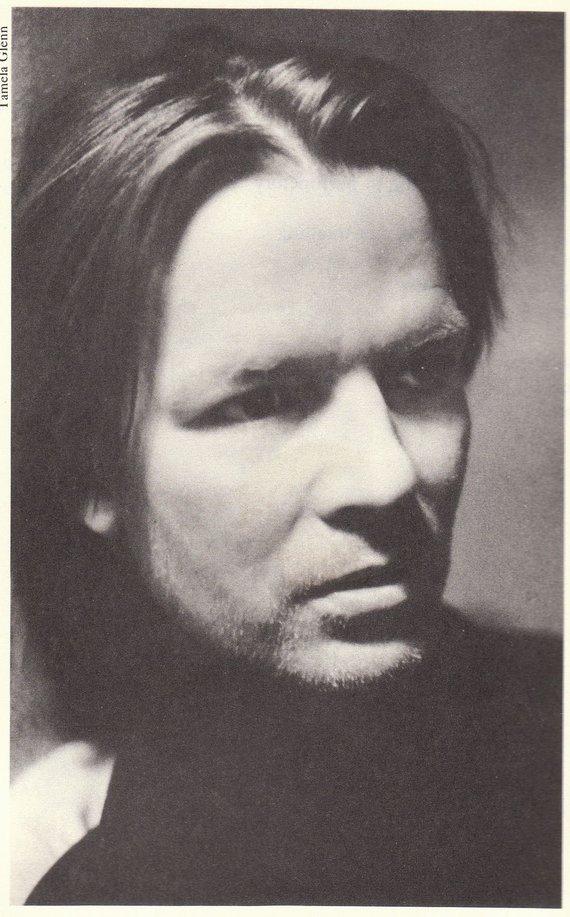

I can’t rationalize my teenage obsession with Jim Carroll in any really satisfying way. From where I stand now, it looks predictable in a way that makes me cringe. I was about 13 when I saw the Leonardo DiCaprio movie of The Basketball Diaries, and while it’s not exactly cool to admit that this adaptation—in retrospect, pretty middling—is what got me into Carroll’s actual diaries and poems, there it is. It didn’t take long after that for me to make him into my morose teen idol. I scrawled his name in the margins of my notebooks and in Sharpie on the wall inside my closet. I Xeroxed his author photo from Fear of Dreaming—his face looking beatific and ageless, his chin scruffy but cheeks dreamily smooth—and taped it up by my bed, near a copy of his prose poem “Reaching France” (“When I reach France, every promise will be kept,” he wrote, sounding both prophetic and world-weary). I kept another copy of the author photo folded up in sixths in my wallet, getting worn and creased into precise little squares.

I can’t rationalize my teenage obsession with Jim Carroll in any really satisfying way. From where I stand now, it looks predictable in a way that makes me cringe. I was about 13 when I saw the Leonardo DiCaprio movie of The Basketball Diaries, and while it’s not exactly cool to admit that this adaptation—in retrospect, pretty middling—is what got me into Carroll’s actual diaries and poems, there it is. It didn’t take long after that for me to make him into my morose teen idol. I scrawled his name in the margins of my notebooks and in Sharpie on the wall inside my closet. I Xeroxed his author photo from Fear of Dreaming—his face looking beatific and ageless, his chin scruffy but cheeks dreamily smooth—and taped it up by my bed, near a copy of his prose poem “Reaching France” (“When I reach France, every promise will be kept,” he wrote, sounding both prophetic and world-weary). I kept another copy of the author photo folded up in sixths in my wallet, getting worn and creased into precise little squares.

It was the kind of fixation lots of people depend on at that age: an intense fandom that becomes a way of identifying, a lust for someone real but half-imagined who you can cling to, idealize, and stubbornly call your own. This elusive, impossible love was the definition of romance to me back then. I coveted the raw, hard-won knowledge that appeared to come from a life of passion and danger and drug addiction. As a relatively sheltered teenager who idealized all sorts of trouble I couldn’t quite bring myself to actually get into, there was nothing more alluring than the survival Jim Carroll seemed to represent.

As I got older, I figured out that he was a writer, not a sage. (One definition of maturity, perhaps?) His words resonated even without my adolescent mania to inflate them. Reading him felt less urgent, which was a kind of loss, but it also felt less fraught. Still, when Carroll died in 2009, the news gave me a weird jolt, my reaction tangled up with the way I knew I would have received it at age 15. I felt like I should light a candle, wear black, do some sort of ritualized mourning—memorializing not just Carroll, no doubt, but the version of myself for whom poetry and its writers were simply beautiful and true. Instead, I made dinner and watched TV before going to bed, wishing I could get myself to feel more stricken.

It was both fitting and terrible to learn that Carroll had died at his writing desk. Not long after his death, I was pleased to hear that Viking would be publishing The Petting Zoo, the novel Carroll had been working on for about two decades. Apparently he’d been “putting the finishing touches” on it, and the book was close enough to completion that it would be an indignity to leave it unpublished and unread. This was reassuring. Carroll may have been gone, but in the comforting, ghostly way that artists do, he would endure.

2.

I got a galley of The Petting Zoo in the mail at some point last summer, and expected to tear through it right away. Instead, I picked it up and flipped through it a few times. I read the first chapter while standing on the subway. I put it down again. I picked it back up and sighed a lot. I was worried about separating my anticipation of the book as an event and a symbol from its actual substance—that I wouldn’t be able to, and also that I would.

I got a galley of The Petting Zoo in the mail at some point last summer, and expected to tear through it right away. Instead, I picked it up and flipped through it a few times. I read the first chapter while standing on the subway. I put it down again. I picked it back up and sighed a lot. I was worried about separating my anticipation of the book as an event and a symbol from its actual substance—that I wouldn’t be able to, and also that I would.

In light of its author’s death, it was hard to approach The Petting Zoo on its own terms, or to arrive at a judgment of it separate from Carroll’s overall legacy. The novel focuses on 38-year-old art star Billy Wolfram as he grapples with fame, lack of inspiration and a pained sort of asceticism in New York City, Carroll’s lifelong home. (“[T]he prime despair came from the realization that my work was totally bereft of the ethereal, or what I call ‘the inner register,’ that ambiguous quality that enables the viewer to approach the painting more from the heart than the intellect,” Billy rambles to a doctor in the mental ward where he does a brief stint early in the book.) Though Carroll was a writer and Billy (mostly) a painter, they share not just a hometown but a precociousness that started to betray them as they got older and more well-known. Where Carroll’s early work grew out of his experiences with drugs and sex, though, Billy “attributed his artistic edge” to his all-around abstinence.

As a New York novel, The Petting Zoo is a many-layered thing, calling attention to the fact that Carroll’s glory days and death played out on the same streets as his protagonist’s artistic crisis, in a city Billy considers “an appendage of his body.” Set in a place that’s been claimed by countless writers in the creation of their own myths, the book raises the question of what Carroll’s fictional New York has in common with his memoiristic and poetic versions, and whether it even matters.

All of this could make for some pretty captivating reading. As a novel, though, The Petting Zoo just doesn’t work. The characters are wooden and the writing is ponderous; the whole thing feels overstuffed but ultimately lifeless and stagy. Oh no, I thought to myself when I finally started reading in earnest. This was not what I wanted to find, critically or sentimentally. That the novel was so disappointing only compounded the heartbreak of Carroll’s untimely death, because it wouldn’t offer the hoped for (and frankly, expected) chance to bolster his reputation. Instead, the book basically contradicts it.

Reviewers had the unenviable task of considering this respected writer in light of what most agreed to be his less-than-inspiring final effort. Many loaded their pieces with biographical information, taking care to mention Carroll’s great earlier work, his influence on other writers, and their own admiration for him. They noted that the novel had been highly anticipated and that ardent fans will love it simply for existing. Actual critical verdicts—which mostly ranged from vague disappointment to outright dismay—were a sort of footnote to wistful considerations of Carroll’s legacy, pre- and post-Petting Zoo.

“With such a burden of context, the novel must show true, great purpose, something Carroll didn’t have time to oversee,” wrote Susanna Sonnenberg in the San Francisco Chronicle. “I wished Carroll was still here to tighten up these bubbling pages, to wrestle all that aching talent under control.” In Bookforum, Brandon Stosuy allowed, “this farewell fits well on the bookshelf with a bunch of other uneven, ‘edgy’ ’80s New York novels. Just pretend it didn’t come out in 2010.” Writing for the New York Times Book Review, Carroll’s compatriot Richard Hell couldn’t find much to praise. The novel’s “strongest discernible structure is in its correspondence to Carroll’s being, to his history and sensibility and psychology,” he reflected. “That’s irrelevant and unfair as literary assessment, but it seems more meaningful to read the novel that way than from any critical standpoint.”

Even the rare complements came off as a little disingenuous, like gestures of deference to a writer who deserved some, maybe especially in death. The book “has its discrete pleasures,” noted Sonnenberg in her Chronicle review. “If The Petting Zoo does not succeed as a novel, as the archeology of the artist, it is fascinating,” wrote Nancy Rommelmann in The Oregonian . And in Bookforum, Stosuy threw the author a bone: “Carroll clearly put a lot of himself into it via loving descriptions of the urban landscape and evocative life-story details.” It’s worth wondering (and impossible to know) whether there would be even this thin generosity had the author lived to stand up to it—or whether the published book might have looked different in that case, and provoked other reactions.

Writing in the New Yorker, Thomas Mallon’s take on the book he calls “depressingly unnecessary” was particularly incisive, if almost painful to read. The book’s protagonist, he writes, is “Jim Carroll methodically stripped of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. The willful absence of all three elements makes for a hero who is not so much pure—in the yearning way of The Basketball Diaries—as weirdly bleached.” In his brutal last line, Mallon imagines “Carroll was at his desk, ransacking the exhausted imagination inside his vanishing body, surely knowing that its very real gifts had long since been spent.”

It’s true that writers rarely get a meaningful say in responding to their reviews (that’s not the point of them, after all), and that readers don’t need an embodied author to make a story come alive. But in the most straightforward way, an author’s existence in the wake of publication is it’s own statement: a plain yet significant “I’m still here.” He can give readings, do interviews, make statements about his work that—even if not in response to specific criticisms—can offer a different entry point. He can write other books. As long as he’s alive, a writer stays part of the conversation about his work, even if he chooses not to participate in it. Without him, things can get a little strange, as fans and critics jockey to have their say—to speak for a writer as much as about him.

3.

In November, to celebrate The Petting Zoo’s publication, Carroll’s old friends Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye hosted a reading and performance at the Barnes & Noble in Union Square. It happened to be the night after Smith won the National Book Award for her memoir Just Kids, which (though focused on her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe) contained a short and poignant section about Carroll, whom she met in the early 70s when both were in their twenties and mostly unknown. The allegiance of the several hundred fans of varying ages in attendance, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on white plastic folding chairs in the sprawling fourth floor events space, was mixed. Many were holding copies of Smith’s book, not Carroll’s.

In November, to celebrate The Petting Zoo’s publication, Carroll’s old friends Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye hosted a reading and performance at the Barnes & Noble in Union Square. It happened to be the night after Smith won the National Book Award for her memoir Just Kids, which (though focused on her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe) contained a short and poignant section about Carroll, whom she met in the early 70s when both were in their twenties and mostly unknown. The allegiance of the several hundred fans of varying ages in attendance, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on white plastic folding chairs in the sprawling fourth floor events space, was mixed. Many were holding copies of Smith’s book, not Carroll’s.

Smith proclaimed that Carroll was “universally hailed as the best poet of his generation,” surely a bit of an overstatement, if a forgivable one. Reading from her brief note that prefaces the novel, she declared, “Jim’s mythic energy is at once laconic and vibrating.” Lenny Kaye pointed out that “Jim’s journey through space and time formed a perfect circle,” because he was born and died in the same neighborhood, “where he was and always will be.” They both read sections of the novel; aloud and out of context, they were even trickier to find a foothold in.

Sitting there, my mind wandering, I wondered what this was like for Smith and Kaye. They looked unruffled, posing for the requisite photos before heading onstage and making their way through an hour-long program that included a few songs along with sections of the novel and the bit from Just Kids in which Carroll makes an appearance. But I figured it had to be surreal for them, no matter how many tributes they’d fronted for dead friends over the decades. Their presence seemed like the execution of some sort of unspoken contract. If you die first, is it the responsibility of your famous friends to help sustain your myth? To read your words to a large crowd in a chain bookstore, and sign their own names in copies of your book?

As the event came to a close, Smith held up a copy of The Petting Zoo and urged the audience to buy one. She was sure, she said, that Carroll had left various scribblings in his notebooks that will come to light, and so she didn’t want to call this book his final words. But “this is what was on his mind,” she told us. “This is what he wanted to give us the most.” If we loved or admired Jim Carroll for any reason, it follows, we have something of a responsibility to receive the book graciously, even gratefully.

A photo of Carroll on the poster promoting the night’s event was the same ageless image I kept in my wallet as a teenager. It sent a pretty clear message about how to best remember him: as beautiful and resilient and full of promise, not the ailing, struggling writer who last read publicly in 2007. While the man in the photograph is Jim Carroll, tellingly, he’s not the author of The Petting Zoo.

Image credit: Pamela Glenn, Jacket photo from Fear of Dreaming.