1.

Leonard Cohen’s world tour ended this month. His road manager maintains a Tumblr, Notes from the Road; it’s a faintly miraculous document, a grainy hypersaturated record of one of the more remarkable musical tours in memory. The last photographs are dated December 12th, the day after the final concert in Las Vegas. Leonard Cohen sits by an airplane window in suit and fedora, half-obscured by the blaze of light over southern California.

It was possible to track the course of the tour through the Tumblr, both the performances themselves and the interludes between them, the bus rides and skylines and green rooms. Two weeks ago I checked the Tumblr and found there the Vancouver skyline, its interchangeable condominum highrises and angled cranes, a constellation of glass towers in constant flux with the mountains of British Columbia in the near distance. I grew up not far from there. There was also a photograph of Cohen in Vancouver—impossibly debonair, per usual—signing something for a fan on a backstage sofa, a bottle of water on the table before him. The caption read Never time to rest.

Leonard Cohen is seventy-six years old. He has been touring almost continuously since May of 2008.

2.

I fell in love with Leonard Cohen’s music in Montreal, the city of his birth. I secretly hoped I might run into him in the eight months when I lived there, but I didn’t, and eventually someone clued me in that he lived in Los Angeles. His influence on my work at that time was enormous. I listened to his “The Stranger Song” over and over again in the period when I was writing my first novel, and it seemed to me later that the song pervades the finished book through and through.

He’s been derided as a writer of songs to slit your wrists to. I don’t agree with this judgment, but it’s not entirely baseless. It’s true that a great many of his songs are surveys of beauty and despair. It’s the kind of music that holds a certain appeal to the adrift, and I had a particular affinity for his work in my first grindingly difficult days in New York City; a period spent trying to forget Montreal, struggling to build some sort of life for myself in a far corner of Brooklyn, escaping into music after long days spent searching for work, dealing with an unmedicated-schizophrenic roommate and writing a) a novel and b) melodramatic journal entries, often hungry and often worried but never doubtful of my decision to come to New York. I frankly doubt there’s a recently heartbroken, financially desperate, recently immigrated novelist in her early twenties on earth who isn’t at least somewhat susceptible to lyrics like “I came so far for beauty / I left so much behind…”

But the sadness of his music isn’t absolute. His songs seem written by a man who recognizes that the world contains great beauty and tremendous hope. It’s a worldview that moves me.

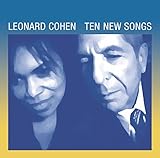

My husband and I listened to Cohen’s Ten New Songs on our first date. When a few years later the startling news came that Cohen was going out on the road after a fifteen-year break from touring, we began to seriously consider flying north to see him. His only tour dates were in Canada. Traveling to hear him live was an extravagant gesture, but we thought there might not be another chance. He was seventy-three years old, and who knew if he’d ever go on tour again? We bought the tickets and flew to Toronto.

My husband and I listened to Cohen’s Ten New Songs on our first date. When a few years later the startling news came that Cohen was going out on the road after a fifteen-year break from touring, we began to seriously consider flying north to see him. His only tour dates were in Canada. Traveling to hear him live was an extravagant gesture, but we thought there might not be another chance. He was seventy-three years old, and who knew if he’d ever go on tour again? We bought the tickets and flew to Toronto.

Apparently we weren’t the only Americans to have this thought. The Canada Customs agent in the Toronto airport asked me what we were doing in Canada for forty-eight hours. I told her we were going to a concert.

“Leonard Cohen?” the customs agent asked.

3.

I have a hard time describing the concerts themselves. I can describe the external details—the way Leonard Cohen makes a point of jogging onstage, his impeccable suit and fedora, the one-fingered piano solo he plays for “Tower of Song”, the way all his musicians wear hats, the breathtaking white cathedral lighting that blazes over the stage during Hallelujah so that the musicians and their instruments all but disappear in the wash of light—but the problem is that words fall flat when describing a religious experience. When the now-extended tour arrived in New Zealand seven months after I stood awestruck in the audience in Toronto, the journalist Simon Sweetman seemed to suffer the same conundrum. “If you were at the concert and didn’t like it,” he wrote, “then you had your information wrong. It is hard work having to put this concert in to words so I’ll just say something I have never said in a review before and will never say again: this was the best show I have ever seen.”

The first time I saw him live, tears came to my eyes. It was one of the great experiences of my life.

4.

The tour began in Fredricton, a small city on Canada’s eastern seaboard. Four weeks later I saw him in Toronto and then the tour went on to Europe, where Cohen played concerts in a zig-zaggy pattern across the landscape, from the UK to Norway to Greece and back to the UK again. A six- or seven-week break after the UK concert, during which time everybody presumably got to go home and see their families, and then the tour reconstituted in Romania. A concert in Bucharest on his seventy-fourth birthday and then across Europe again, a different route.

Leonard Cohen’s stage patter doesn’t change much between cities: variations on “It’s wonderful to be back here again. The last time I was on this stage was fifteen years ago, when I was sixty, just a crazy kid with a dream.” He’ll sometimes list the psychotropic medications he’s taken since then (“Prozac… Celexa… Effexor…”) Attending a Leonard Cohen concert is a financially enervating experience. Cohen seems aware of this; it’s not unusual for his stage patter to include an apology to the audience for any “geographic and financial inconvenience” involved in being here with him this evening.

It had seemed in the beginning that there might only be a few dates, only in Canada, but in 2009 he was still touring, and a few weeks after he awed Simon Sweetman in New Zealand, he arrived in New York. We agonized briefly over whether to attend. The ticket prices were substantial and we’d just seen him the year before, but he’d turned seventy-four by now, and how many more opportunities would there be? The Beacon Theatre is a horrifically ill-managed venue—there was a terrifying moment before the concert when I feared I might actually be crushed in the crowd out front—but his concert there was as inspired as the one we’d attended in Toronto the previous year.

There is something tremendously moving about him. You get the sense that he’s giving absolutely everything he has. He introduces his musicians repeatedly and takes his hat off to listen to their solos. He thanks the crew at length, occasionally with a special mention for the woman “who takes care of our hats.” (On this particular tour, this was clearly an important job. There are a lot of fedoras on stage.) His final goodnight comes only after multiple encores, multiple standing ovations.

In both concerts I saw, the horn player threw his hat into the air as the band left the stage. It wheeled up impossibly high and descended in the fading lights. Both nights the crowd seemed caught up in a sort of ecstasy, and the feeling, apparently, is mutual: “The concert comes to a climax of energy and emotion,” said Cohen’s backup singer Hattie Webb in The Oregonian, “and we all leave the stage undoing our ties and waistcoats with a feeling that it has been a momentous night.”

5.

We went to see The National perform in Prospect Park a few months ago, on the kind of perfect summer night that makes you remember why you moved to Brooklyn in the first place. The lead singer mentioned that they’d just returned from Europe, and that they were playing on borrowed equipment; their gear had gotten mixed up with Leonard Cohen’s.

It was startling to realize that Cohen was still out there, touring endlessly. On the night we listened to The National in Brooklyn, Cohen was on stage in Salzburg, Austria. Summer 2010, the tour slipping into its third year. There had been a few breaks, but not many; they took a few weeks off after that night when we saw them at the Beacon Theatre, and then they went on to Texas. Through the United States and back up into Canada, back down into the United States again, across Europe.

There was a bad night in Valencia when Cohen fainted on stage during “Bird on a Wire”, three days before his seventy-fifth birthday. He was suffering from food poisoning, but hadn’t wanted to cancel the concert and disappoint his fans. He was rushed to hospital, spent a weekend recovering in a hotel room, and performed in Barcelona on his birthday.

On into Israel, where the Cohen tour brushed off threats from the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel and played a sold-out show in Tel Aviv. Cohen blessed the concertgoers in Hebrew at midnight, three days before Yom Kippur.

6.

The tour left Australia on November 25th, returning to North America for the final time. The Notes From the Road Tumblr shows photos of the departure from Perth, the tarmac in Bali and the Hong Kong airport, lines of sulphurous lights. Photographs of the crew and musicians, together in yet another airport. They have been traveling together for a very long time. “Cohen’s performance Thursday in Vancouver,” wrote Mike Devlin in The Vancouver Sun, “will be show No. 242 on the schedule. When the trek comes to a close in December, its final tally will likely read a staggering 247 dates completed, more than 6,000 songs performed and approximately 741 hours of onstage greatness.”

On December 11th, Leonard Cohen performed in Las Vegas. There are no further dates on the calendar. I toyed briefly, irrationally, with the idea of flying down to see him one more time before the end of the tour. It wasn’t really possible. The last concert photograph was taken onstage: Leonard Cohen stands before three tiers of fans at Caesar’s Palace, a thin man in his seventies in an impeccable suit, his hair a little creased at the back from his fedora. The crowd is on their feet and he holds his hat up in the air. He’s thanking them, he’s saluting them, he’s saying goodnight.

It would be wonderful to imagine that I’ll see him perform again in my lifetime. If I don’t, I’ll still feel impossibly lucky that I got to see him at all.