1.

1.

A few weeks ago, in a small town in the southern Netherlands, I found myself in a cramped and musty used bookstore. If the bookshop was small, the section of books in English was miniscule, barely taking up two thin shelves. Not expecting much, I stumbled upon not one but two copies of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The price, at a euro fifty, was right, and I snagged one of the copies off the shelf.

2.

Back when I was in college, not all that many years ago, back when I read more books in an average week than I do now in a good month, I picked up Kundera’s magnificent novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. I think I read the whole novel in one sitting, a rare occurrence. It’s a book I still think about fondly. For me, the best books are the ones that do not sacrifice form for function or function for form. That is, the writing must work well both stylistically and on the plain level of plot, and I remember The Book of Laughter and Forgetting doing both.

Back when I was in college, not all that many years ago, back when I read more books in an average week than I do now in a good month, I picked up Kundera’s magnificent novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. I think I read the whole novel in one sitting, a rare occurrence. It’s a book I still think about fondly. For me, the best books are the ones that do not sacrifice form for function or function for form. That is, the writing must work well both stylistically and on the plain level of plot, and I remember The Book of Laughter and Forgetting doing both.

I meant to pick up The Unbearable Lightness of Being immediately upon finishing Laughter and Forgetting, but something else got in the way. Maybe it was Joyce, maybe it was Faulkner, maybe it was some obscure book of Twain’s that I needed to reread for my thesis. I don’t remember anymore, but Kundera somehow fell by the wayside, and I never read what today I assume is his masterpiece.

3.

If it hadn’t been for a fortunate coincidence, I probably would have let The Unbearable Lightness of Being sit on my shelf for another few months or years while I made my way through the books in a to-be-read pile that never seems to grow any smaller.

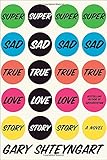

The day after my purchase of Lightness, I happened to be reading a review of Gary Shteyngart’s new novel, Super Sad True Love Story. I am a big fan of Shteyngart, and am just as excited to delve into his new dystopian world as I was to devour his painfully funny novel Absurdistan. In the course of reading the review, I was surprised to find that The Unbearable Lightness of Being plays a semi-significant role in Shteyngart’s new work. Apparently one of the protagonists of Love Story, a bibliophile in an age of hyperactive technojunkies, in which books are all but obsolete, dreams of reading passages of Lightness to his girlfriend in bed.

The day after my purchase of Lightness, I happened to be reading a review of Gary Shteyngart’s new novel, Super Sad True Love Story. I am a big fan of Shteyngart, and am just as excited to delve into his new dystopian world as I was to devour his painfully funny novel Absurdistan. In the course of reading the review, I was surprised to find that The Unbearable Lightness of Being plays a semi-significant role in Shteyngart’s new work. Apparently one of the protagonists of Love Story, a bibliophile in an age of hyperactive technojunkies, in which books are all but obsolete, dreams of reading passages of Lightness to his girlfriend in bed.

After reading the review, I did a little Googling and discovered that Lightness is indeed considered one of those romantic books that lovers have been reading to each other in bed for decades.

A romantic Czech novel endorsed by a character in a Shteyngart novel? The coincidence, along with the approbation, was almost too much to bear.

I decided to eschew the pile of novels currently sitting on my nightstand for the moment, and jump right in to Lightness.

4.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is one of those books that you don’t know you need to read until after you’ve read it.

Possibly the perfect post-modern novel (written in the early eighties, at what I think of as the zenith of the post-modern period), Lightness plays wonderfully inventive games with the reader without sacrificing an iota of plot or detail. The book is written in a close third person, with the omniscient narrator butting in every now and again to provide commentary and remind the reader that the characters you are reading about and identifying with are his creations and nothing more.

The book’s first five chapters form a chiasmus (A-B-C-B-A). The outsides of the chiasmus follow the story of Tomas, a Prague physician and philanderer who makes a point of sleeping in his own bed alone every night, while at the same time sleeping with hundreds of women.

Tomas meets Tereza, a waitress from a small Czech town whose personal story is followed in the B sections of the chiasmus. Tomas is unbearably stricken with Tereza: “It occurred to [Tomas] that Tereza was a child put in a pitch-daubed bulrush basket and sent downstream. He couldn’t very well let a basket with a child in it float down a stormy river!”

A paragraph later, Kundera’s narrator explains: “Tomas did not realize at the time that metaphors are dangerous. Metaphors are not to be trifled with. A single metaphor can give birth to love.”

5.

The center of the novel’s chiasmus, the C-section, tracks the life of Sabina, an artist who is for a time a lover of Tomas and a rival/mentor of Tereza.

Near the end of this third section of the book, long before the novel is over, we learn that Tomas and Tereza died in a car crash. The rest of the book backtracks and details the lives of Tomas and Tereza, although now, of course, everything is different. Now we know that their every step foretells an impending doom.

6.

The protagonist of Super Sad True Love Story, the one who wanted to read The Unbearable Lightness of Being to his girlfriend in bed, had it wrong. Lightness is anything but a love story. At the very least, it is not a love story one should desire to read in bed to their beloved.

Tomas, the book’s main character, cannot stay faithful to his lover and wife Tereza. He spends the bulk of their lives together cheating on her, so she goes to sleep at night smelling “the aroma of a[nother] woman’s sex organs.” When he finally does come around and stop sleeping with other women, it is only because they are living in a small hamlet in the countryside, and there are no eligible women available.

Tereza, for her part, becomes so disenchanted with the love she has for Tomas that she dreams continually of his abandonment and her suicide, or alternately of his ordering her execution. It becomes so bad that, even after they move to the country, even when Tomas is a beaten down and weary old man, she still suspects him of cheating on her.

7.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is not a love story. It is a story about survival in the face of a power so overwhelming there is nothing one can do to stop it.

Tereza survives Tomas’s overwhelming destructiveness. Tomas survives the loss of his position as a doctor and, along with it, his sense of purpose, in the face of Soviet repression and Czech indifference.

The both of them survive a lifetime of pain together, until they don’t. The two of them die, together. Their death is hidden somewhere in the middle of the book, and it doesn’t mean a thing.

8.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is a love story. It is a story about two people surviving together in the face of a power so overwhelming there is nothing they can do to stop it.

It is a story of two people who die together, needlessly and hopelessly in love.

9.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is full of coincidences. In fact, the novel can easily be read as a treatise on the nature of coincidence.

Tomas broods throughout the book on the nature of his relationship with Tereza:

Seven years earlier, a complex neurological case happened to have been discovered at the hospital in Tereza’s town. They called in the chief surgeon of Tomas’s hospital in Prague for consultation, but the chief surgeon of Tomas’s hospital happened to be suffering from sciatica, and because he could not move he sent Tomas to the provincial hospital in his place. The town had several hotels, but Tomas happened to be given a room in the one where Tereza was employed. He happened to have had enough free time before his train left to stop at the hotel restaurant. Tereza happened to be on duty, and happened to be serving Tomas’s table. It had taken six chance happenings to push Tomas towards Tereza.

That afternoon a few weeks ago, I too suffered six chance happenings. I happened to be in Den Bosch. I happened to wander down a small side street and notice a tiny bookshop. I happened to go in and notice a worn copy of a book I had wanted to read for a number of years. I happened to purchase it, planning to put it aside and read it some time in the future. The next day, I happened to read an article about a book by a contemporary writer I greatly admire, touting (if only through that book’s narrator) the book I had just picked up. As I read the article, I happened to have the book by my side, so I could begin to read it immediately, before life got in the way.

Six coincidences that are not really coincidences. After all, isn’t everything we do a coincidence? I choose to walk down street A over street B. I meet a woman on street A I would have missed had I walked down street B. We fall in love. We get married. We spend our life together.

Is my walking down street A and not street B a coincidence? Had I walked down street B and met a different woman and spent a similar life with her, would that have been a coincidence as well?

Life, all life, can be read as coincidence, as a series of happenings that could just as easily not have happened. But where does that leave us?

Nowhere. Looking back, like Tomas, wondering how different things would have been had he chosen street C or street Z.

10.

By the end of the novel (not the middle of the novel, where Tomas and Teresa are killed, but the end of the novel, where they are hopelessly alive), Tomas has stopped his endless questioning. There is no more what happened to be. There is only what is.

In this manner, the experience of reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being is reflected in the text itself.

Sure, it was a coincidence that I stumbled on this book and almost immediately read it after years of benign neglect. But the coincidence isn’t what matters.

What matters isn’t what street you walked down. What really matters, ultimately, is that you married the woman you met walking down street A.

What really matters is that you read this magnificent book. And, of course, that reading the book changed your life.