“The gizmo, the golden, deceptive, brass-filled gizmo, was gone at last.” So reads the final sentence of Jim Thompson’s con-man sleaze-romp The Golden Gizmo, which I finished last week. Though it ran under 200 pages, the story was crammed with double-crosses, faked deaths, and a massive talking dog. There were shady gold dealers and exiled Nazis, a femme fatale and a hag of a wife. I’d been mildly confused throughout, but the ending tied things up efficiently enough. I had questions, but not many complaints. After rereading the final line, I admired the cover image: a grainy photo of hundreds being shuffled. I flipped to the last page and inspected books “Also Available From Jim Thompson.” And with that, I had squeezed all that I could from The Golden Gizmo. I returned it to its narrow gap on the shelf, scanning the books that I hadn’t yet read. But I didn’t pick a new one, not just yet.

“The gizmo, the golden, deceptive, brass-filled gizmo, was gone at last.” So reads the final sentence of Jim Thompson’s con-man sleaze-romp The Golden Gizmo, which I finished last week. Though it ran under 200 pages, the story was crammed with double-crosses, faked deaths, and a massive talking dog. There were shady gold dealers and exiled Nazis, a femme fatale and a hag of a wife. I’d been mildly confused throughout, but the ending tied things up efficiently enough. I had questions, but not many complaints. After rereading the final line, I admired the cover image: a grainy photo of hundreds being shuffled. I flipped to the last page and inspected books “Also Available From Jim Thompson.” And with that, I had squeezed all that I could from The Golden Gizmo. I returned it to its narrow gap on the shelf, scanning the books that I hadn’t yet read. But I didn’t pick a new one, not just yet.

In recent months, that moment of lingering, of browsing my own library, has become one of my favorite aspects of reading. In the past, I’d immediately swap the book I’d just read for a new one, a literary chain-smoker. But now I take my time—luxuriating in possibility, enjoying expectation, and pondering what’s next with a real, idle pleasure.

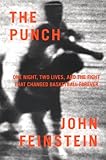

And after finishing the Thompson book, my options seemed endless. I’ve lately been in stockpile mode, picking up The Curious Case of Sidd Finch, Lush Life, and A Prayer For the City. A friend had given me Lonesome Dove, The Bronx is Burning, and Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life. There was The Punch, about Kermit Washington’s near-fatal swing at Rudy Tomjanovich during a 1977 NBA game. And of course, the dozens of titles—by T.C. Boyle and Frank Herbert, Pete Dexter and Chris Elliot—that I’ve owned for years and have never quite gotten to. From all of these, I happily chose nothing.

And after finishing the Thompson book, my options seemed endless. I’ve lately been in stockpile mode, picking up The Curious Case of Sidd Finch, Lush Life, and A Prayer For the City. A friend had given me Lonesome Dove, The Bronx is Burning, and Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life. There was The Punch, about Kermit Washington’s near-fatal swing at Rudy Tomjanovich during a 1977 NBA game. And of course, the dozens of titles—by T.C. Boyle and Frank Herbert, Pete Dexter and Chris Elliot—that I’ve owned for years and have never quite gotten to. From all of these, I happily chose nothing.

Instead, I let my mind drift around the books’ edges, nourished by thoughts of what they would bring: Plimpton’s erudite humor, Price’s ordered chaos, Bissinger’s knowing outrage. I could conjure T.C. Boyle’s dexterity and Pete Dexter’s toughness. Though I denied myself the satisfaction of engagement, I also avoided disappointment: did I really need to read a 1,000-page western—or, for that matter, anything by Chris Elliot? I don’t even really like westerns, and Get a Life was axed when I was still in Reebok Pumps. Better, perhaps, to let those remain abstract and idealized.

In this nebulous state, anticipation is also fed by jacket design. The Punch looks especially awesome: the cover is spare, with bright orange type over a blown-out picture of the titular incident. It’s violent, discomfiting, hard to ignore. The book looks so good that, to be honest, I don’t want to spoil things by actually reading it—getting bogged down, as I suspect I will, in the minutiae of Carter-era neurology and Kermit’s deep regret. Nonetheless, The Punch calls to me. Knowing the sex won’t be as good as you’ve dreamed is no reason to keep your pants on.

In this nebulous state, anticipation is also fed by jacket design. The Punch looks especially awesome: the cover is spare, with bright orange type over a blown-out picture of the titular incident. It’s violent, discomfiting, hard to ignore. The book looks so good that, to be honest, I don’t want to spoil things by actually reading it—getting bogged down, as I suspect I will, in the minutiae of Carter-era neurology and Kermit’s deep regret. Nonetheless, The Punch calls to me. Knowing the sex won’t be as good as you’ve dreamed is no reason to keep your pants on.

Post-Gizmo, I spent five days like this—weighing my options, considering my desires. I caught up on my comic books and magazines, cleared out unread newspapers. And then, with private fanfare, I walked upstairs for a book. I’d recently bought And Here’s the Kicker, a collection of comedy interviews—but after glancing through it, I found I wasn’t in the mood. Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla was enticing, but something—maybe its candy-colored fight-night cover—pushed me past. The Punch, too, would have to wait. In the end, I picked Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life. It looked breezy and smart, and had come highly recommended. I took it down, laid in bed, and began to read. It was wry and nostalgic, serious and absurd. I’d made the right choice. It even contained a line I found relevant to my dilatory new habit: “Most of us go about our duties of commerce and leisure in a state of perpetual longing.” I thought about that. My postponement of reading was a way to embellish that longing, to make it even more deliciously perpetual. After thirty years, I’d found one more way to wring enjoyment from books—even as they sat on the shelf.