I’ve been writing a lot about film adaptations lately, so I was thrilled to stumble onto this very cool series at the Guardian which each week is turning a critical eye on a new famous film adaptation. The latest is on Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 1986 version of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose.

More Adaptation Mania

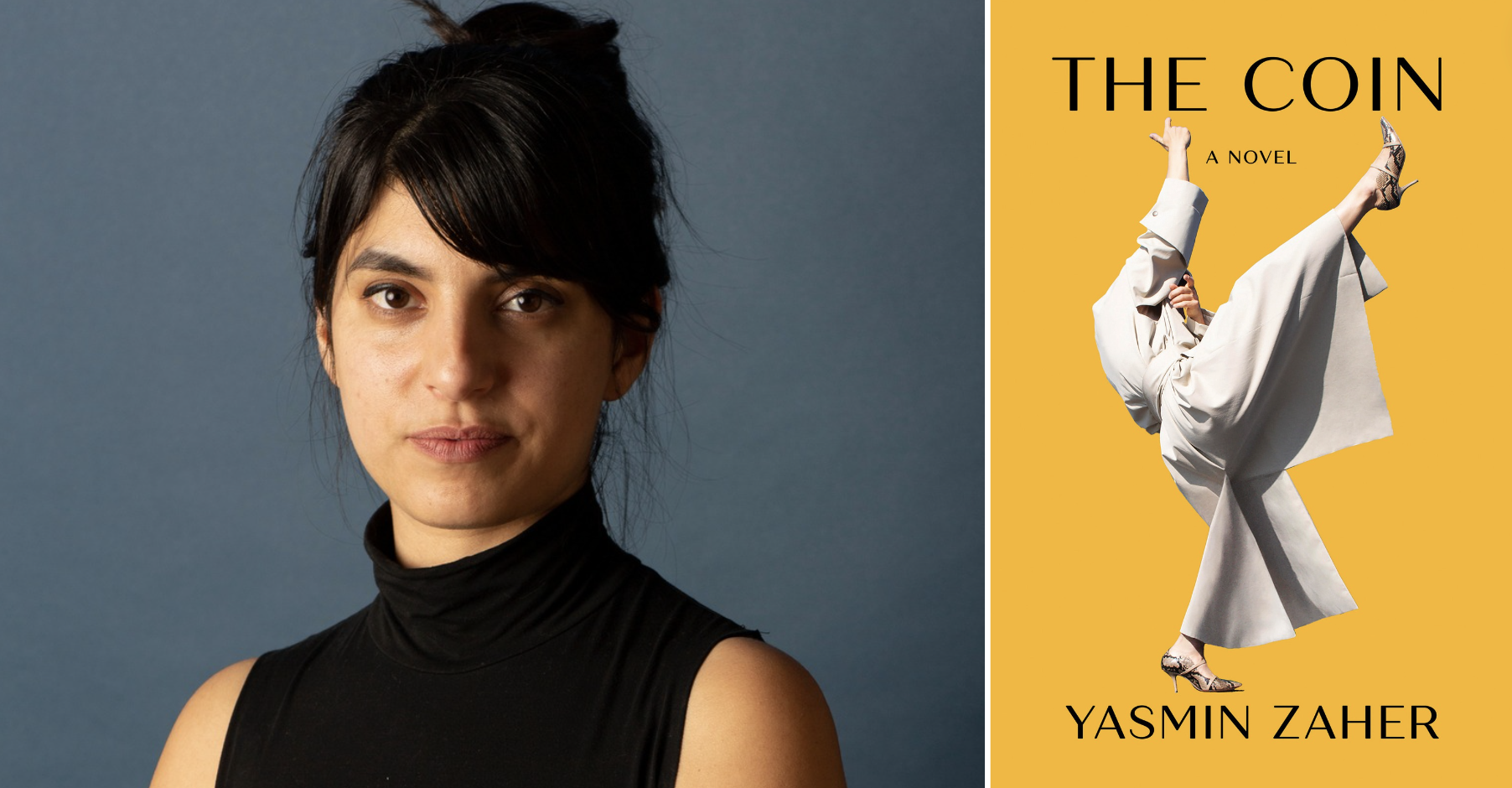

How Yasmin Zaher Wrote the Year’s Best New York City Novel

"This is going to sound absurd, but in a novel, you can say the truth, and in journalism, you cannot."

●

●

●

Things Got Weird: On the Early ‘90s Crack-Up

Ganz vividly renders the early 1990s’ shouty yet blankly confused alienations along with the endlessly gassy and vituperative “whither America?” debates.

●

●

●

●

●

●

The Beguiling Crónicas of Hebe Uhart

'A Question of Belonging' is marked by an unerring belief that a good story can be found almost anywhere.

●

●

●