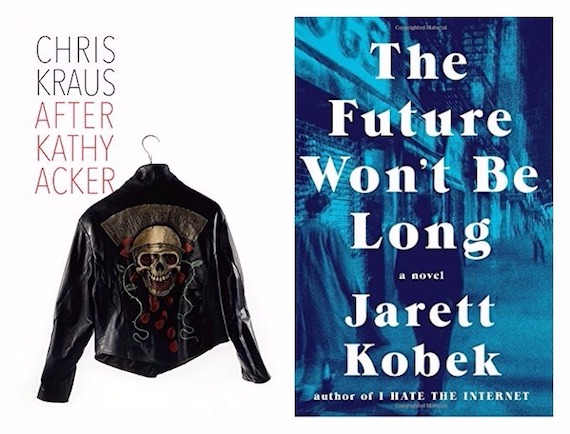

Chris Kraus’s After Kathy Acker is one of the best books of the year. A biography of an elusive, and barely understood, literary figure, it’s also a secret history of a certain time and place. When I read an advanced copy, I couldn’t stop talking about the book. This included a conversation with Kraus’s Semiotext(e) co-editor Hedi El Kholti. He suggested that Chris and I should have a conversation about our two books. I hadn’t even thought of it, but it made a certain sense: my new novel, The Future Won’t Be Long, is concerned, roughly, with the same time and place as Chris’s book. Which is to say New York. The dirty New York. Before Giuliani and gentrification. And, besides, Chris Kraus changed my life. Literally. She was the editor on my novella ATTA, which Semiotext(e) published back in 2011. It’s all gone weird from there.

A few weeks ago, we managed a conversation about our new books. Here’s the result.

Jarett Kobek: I guess the best place to start is to explain our two books and then move forward. Your book, After Kathy Acker, is a formidable biography of a foreboding figure, Kathy Acker. As you know better than anyone, it’s impossible to summarize the whole of Acker’s life in a sentence, but to give an ultra-uninformative biopsy: writer, artist, performance artist, minor-literary celebrity, with a deep connection to New York and its era of transgressive art.

My book, The Future Won’t Be Long, is a novel about (amongst other things) the East Village in the mid- to late-‘80s and early- to mid-‘90s, and is concerned with lives and secret histories in the aftermath of the real heyday of the transgressive moment. If I were to give a snippet summary, I could do worse to say that its characters exist in a world that came after Kathy Acker.

A few months ago, I read Angela Nagel’s Kill All Normies. I don’t know if you’ve gotten to it, but it’s supposed to be a book about the rise of the Alt Right. But it’s curious, because her book ends up being a meditation on the value of transgression as a strategy, and how the Alt Right succeeded on a roadmap of co-opting and adopting this strategy. This would seem to be the entire methodology of the presidency: transgress all social norms and then, while the world plays catch up, transgress again. So now everyone’s like the characters in The Future Won’t Be Long. We’re all living in a world that comes after Kathy Acker.

A few months ago, I read Angela Nagel’s Kill All Normies. I don’t know if you’ve gotten to it, but it’s supposed to be a book about the rise of the Alt Right. But it’s curious, because her book ends up being a meditation on the value of transgression as a strategy, and how the Alt Right succeeded on a roadmap of co-opting and adopting this strategy. This would seem to be the entire methodology of the presidency: transgress all social norms and then, while the world plays catch up, transgress again. So now everyone’s like the characters in The Future Won’t Be Long. We’re all living in a world that comes after Kathy Acker.

All of this is a very long-winded way of asking you to do the least envious of things, which is to iron out the ambiguity of your title. What does it mean in 2017 to be after Kathy Acker?

Chris Kraus: Matt Fishbeck suggested that title, and frankly, I didn’t think about it that much. It just sounded right. Mostly, I guess because, as you say, it evokes the distance between her era and the one we’re living in now. And my approach to writing the book was to write through that distance.

Transgression has become so banal. Even within Kathy’s lifetime, by the time she left the East Village, a new generation of people like Richard Kern and Nick Zedd had far surpassed her transgressive capital. I mean, Joe Coleman was biting the heads off of rats in his performances, and how do you compete with that? If you have any sense, you don’t even try. Kathy was actually quite critical of that work, in some of her letters.

Your book is an incredibly precise and inspired evocation of a decade, 1986 to 1996. Without seeming to be one, or taking history as its literal subject, it captures the difference in consciousness, the texture of life, that’s emerged since those years. For one thing, the characters — who, as they themselves admit, aren’t all that remarkable, they’re lumpen-creatives, more or less — are formidably informed, as only savants are today. There’s a great line in Gary Indiana’s Resentment where Seth, the narrator, observes during a night-long group adventure, how each half-generation seems so much less informed than the last. Were you consciously trying to depict the difference in culture between then and now?

JK: We’ve entered an era in which, in theory, anything goes and yet everything is so much more restrictive than it was 20 years ago. The rules are subtle until you bang up against them. You have an excellent example of this in After Kathy Acker, when you write about the case of the writer Janey Smith and his fuck list, a moment in which it became clear what aspects of Acker’s work had been adopted and repurposed and what’s been rejected.

The idea was with Future was, exactly as you suggest, about making a contrast between then and now. I have officially reached a point in my life where I’ve started sounding old, but I have an inescapable sense that we’re in an era of calcification. The 21st century has turned everything that was even remotely interesting from the 20th century into a kind of religion, completely with dogmas and priestly castes. I thought it would be interesting to take a look at what turned out to be a transitional moment before the hardening had fully set in. As lumpen-creatives, the characters are haunted by a past that was much more interesting than the one they’re living (at any given moment, New York is always better 10 years before, but in their case it’s true) and they’re also haunted by a future that’s about to hit them harder than they can imagine. With one exception, none of them are even particularly good with computers!

Which reminds me: towards the end of Acker’s life, it’s a different story. You paint a portrait of someone, just before her death in 1997, who is totally addicted to her computer and the nascent online world, a place where almost everyone would end up 10 years later. Do you think this was a result of her own exhaustion/disappointments with the role she’d found herself in, or was it an expansion of her previous work?

CK: By the mid-’90s, Kathy hit a wall, both creatively and in terms of her career, that must have been very painful. Her last two novels, Empire of the Senseless (1988) and In Memoriam of Identity (1990) had not been well received, at least not critically or within the literary world, in NY or London. She was living in San Francisco, drifting further to the margins of what she’d previously considered central. To me, the great poignancy of Acker’s life was that she’d outlived her dream. Literature, capital L, was no longer important in the same way. The time when writers could be cultural heroes was already over. Her publisher, Grove Press, was bought and sold twice in the last few years of Acker’s life…publishing had already become corporatized and hegemonic. Her writing had become somewhat repetitive, and so non-narrative that it was unreadable by many, and she hadn’t figured out another way. But she was trying. Rather than change her writing style, she looked to aspects of internet culture as mirrors of her own interests: avatars as a means of escaping fixed identity in gaming; the intricacies of coding as a metaphor for consciousness. Still, she wasn’t stupid. She already saw the limits of the internet, and I’m sure if she’d lived longer, she would have pursued entirely new directions.

CK: By the mid-’90s, Kathy hit a wall, both creatively and in terms of her career, that must have been very painful. Her last two novels, Empire of the Senseless (1988) and In Memoriam of Identity (1990) had not been well received, at least not critically or within the literary world, in NY or London. She was living in San Francisco, drifting further to the margins of what she’d previously considered central. To me, the great poignancy of Acker’s life was that she’d outlived her dream. Literature, capital L, was no longer important in the same way. The time when writers could be cultural heroes was already over. Her publisher, Grove Press, was bought and sold twice in the last few years of Acker’s life…publishing had already become corporatized and hegemonic. Her writing had become somewhat repetitive, and so non-narrative that it was unreadable by many, and she hadn’t figured out another way. But she was trying. Rather than change her writing style, she looked to aspects of internet culture as mirrors of her own interests: avatars as a means of escaping fixed identity in gaming; the intricacies of coding as a metaphor for consciousness. Still, she wasn’t stupid. She already saw the limits of the internet, and I’m sure if she’d lived longer, she would have pursued entirely new directions.

I agree with you about the calcification, and the rules. The present’s very puritanical. In both our books, there’s an ethos of self-destruction, of losing yourself however possible, that’s been replaced by rigid self-protection. But at the same time — there were definitely winners and losers in that game. Towards the end of the novel, you have that beautiful passage: This is how the world works…in talking about who does, and doesn’t take the blame for Angel Melendez’s murder. I always thought the double standard between self-destruction and self-advancement was one of the hypocrisies that’s been edited out of memoirs and other histories of that era. Do you agree?

And, I’ve got to ask – what about the murders? Really, two of the most central events in The Future are the grisly murders of Monika Beerle and Melendez — murders “shared” by their communities.

JK: Future was intended to be a much shorter novel, purely about the Club Kids. As I wrote, the book kept expanding. I remembered Daniel Rakowitz and Monika Beerle.

For the readers who don’t know about either of the killings: Daniel Rakowitz was a guy who wandered around the East Village in a religious delusion. He was considered a more-or-less harmless nuisance. Then he moved in with Monika Beerle, who was a dancer at Billy’s Topless, and very shortly thereafter killed her. Because of the grisly circumstances, the story was one of those New York infamous crimes. Rakowitz dismembered Beerle’s body in a bathtub, boiled the head on his stove, and then apparently served the broth to homeless people in Tompkins Square Park. When he was finally arrested, Rakowitz brought the cops to a locker in the Port Authority, where he’d stored Beerle’s skull in a tub of kitty litter.

Angel Melendez was Michael Alig’s drug dealer. Michael was King of the Club Kids, a loose group of kids who hung around the city’s nightclubs and performed all kinds of outrageous antics, and who ended up getting a huge amount of media coverage. In 1996, Angel went to Michael’s apartment and ended up killed by Michael and a guy who called himself Freeze. Angel’s body was dismembered in a bathtub. Then Michael and Freeze dumped Angel in the river. The story played out in the press for months and months until Michael was arrested.

What I didn’t know until I started doing research is how much the two murders paralleled each other. Much like Michael Alig’s murder of Angel, everyone knew. Possibly an even greater number than knew about Alig killing Angel. Alig at least hid the body from his friends and played coy, sometimes saying he did it, sometimes saying he didn’t. Rakowitz showed people the remains. He told a ton of people that he had murdered Beerle. And like the murder of Angel, it took forever before there was any official involvement.

With Michael, everything was fabulous. Even murder. But Rakowitz was just squalor. So it seemed absolutely vital to include. To strip away the glamor. No one posts to Tumblr about Rakowitz being fabulous.

There’s an easy narrative about these killings — a story about how excess ends in horror. I don’t subscribe to that, but I do think the killings speak to something about the social scenes that end up lionized in books like mine. It sounds horribly dated describing it like this, but if you try to create a lawless society of outsiders, essentially a world without critical judgment, then the real temperature of that scene is taken when someone’s actions force you into a situation which manifestly demands judgment. And nothing does that like forcible death. This gets us back to the question about self-advancement and self-destruction. Because I agree, it’s almost always hidden. But there are always winners and losers. And I think it may be the same conditions which produce a blindness about it.

CK: Yes, that’s really interesting. Your book describes a period of total decadence, the last days of the underground empire, before the fall. I didn’t see that before, but the way these ‘communities’ react to the killings puts everything into focus. I was very aware of Monika Beerle’s murder – horrified by it. In my film Gravity & Grace, her killing kind of a secret subtext…the character Gravity has made a kind of stained-glass graphic novel depiction of it, installed on the panes of the French doors in her slummy apartment. Although mostly during that period, I remember the hordes of people selling their belongings on blankets in the street, and the rash of break-ins and petty crime in the East Village. You couldn’t park a car in the street without it being keyed or broken into. You write about the destruction of the Tompkins Square Park bandshell — the way someone painted over the Billie Holiday mural. I remember when that mural went up — my then-boyfriend Bud Hazlekorn helped to paint it. We’re seeing the same thing now in Lincoln Park, Boyle Heights, and MacArthur Park in Los Angeles. Vandalism is the last gasp of resistance. In The Future, Baby and Adeline and their friends are just living their lives, but of course they’re part of the force of gentrification. And people like the drag queen Christine/Christian in your book just disappear in the most sordid, but wholly predictable ways. There’s a whole population that becomes the collateral damage of “the democratization of lust,” as Baby puts it, or excessive freedom. As the former Urizen publisher Michael Roloff told me, when I interviewed him for the Acker book,“What looked like the ‘greening of America’ in that neck of the woods metamorphosed into the wildest kind of neo-liberalism down in Tribeca and the East Village.”

JK: Speaking of complicity. It sounds absurd, given that Future is populated by historical figures, but including Beerle (as necessary as I found it) has sat poorly with me. That’s a human being whose murder has reduced her to a story about Rakowitz. Which is one that I have used and now participated in. What I’ve done is in some ways the antithesis of what you’ve done with Kathy Acker, but I wonder if there was any hesitation on your part in taking on a biographical project of someone who (I assume) you personally knew? Not so much in terms of the exposing Acker, but exposing yourself, linking yourself to the story?

CK: I didn’t know Kathy at all, and I think that made it easier to work on the book. As I wrote diplomatically in a publicity piece for the book, “our two brief social meetings were tinged with antipathy.” That is: she reflexively disliked me because a) I was no one, and b) I was married to Sylvere, who she’d been close to. For those reasons, and others, I thought it best to leave myself out of the story. But Kathy and I knew many of the same people, and we shared the same cultural influences. Writing about Kathy became a way of writing a revisionist history of New York in the 70s and 80s, just as you do in The Future for the following decade.

But getting back to “the democratization of lust” and neoliberalism: Your first novel, ATTA, is a nuanced and unsentimental psychobiography of the 9/11 suicide bomber. The book never justifies Mohamed Atta’s actions, but it steps back far enough from reflex moral condemnation to consider his rationale and motivations. Atta’s master’s thesis critiqued the introduction of Western-style skyscrapers in the Middle East and called for a return to the “Islamic-Oriental city.” Your radically propose that, at least in his mind, the destruction of the World Trade Center was a form of architectural criticism. Do you think your background as the son of a Turkish Muslim immigrant has given you a different perspective on the value of “freedom,” and how these values play out psychically and geographically?

JK: I think the hardest thing to talk about when it comes to neoliberalism is how, particularly in the era of the Internet, everyone is to varying degrees complicit in its relentless process of change. You literally cannot live in the US without exhibiting some complicity. There’s obviously different degrees in this assessment, but that’s been my life experience from the moment that I moved to NYC. The changes of the Giuliani era were performed, essentially, for my benefit. So it was very important to make sure that the characters in Future were situated in a time when they couldn’t be anything but gentrifiers, but who (perhaps with the exception of Adeline) see themselves as existing in resistance to the surrounding society. But they are of course key components of society’s forward march. The future really won’t be long.

The moment for me of brutal awakening (the process is ever ongoing) was 9/11. As you mention, I’ve got a personal connection, which is that my father was a Muslim immigrant to America. What happened on 9/11 was this: the least interesting thing about the man suddenly became the most important. He went from 20+ years experiencing literally no animus or prejudice to someone who climbed down a fire-escape at 5 a.m. to avoid his neighbors beating the shit out of him. He eventually left the country, which has been hugely damaging in some ways. If nothing else, his apartment in Turkey has given me a staging ground for travel around the Middle East.

But yes, I think that 9/11 and ensuing years of an endless American dialogue about Muslims — one which creates endless wars despite the political party in office and which on all sides has nothing to do with the lives of any Muslims I know or to whom I related — has caused me to become increasingly obsessed and skeptical about almost everything.

So that’s the reason, really, I was interested in writing a revisionist history. You mention that you used Acker’s bio for the same purpose. Why did you think it was necessary?

CK: Richard Hell’s memoir, I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp, mentions Kathy in passing, a reference to some kinky-sex episode they had. And of course Richard wasn’t writing a book about Kathy, but I thought she deserved better than that. All of these memoirs and novels, photo exhibitions and films, were coming out about that era, the romance of the last avant-garde. And I found those depictions false. They necessarily edit out the texture of life: the boredom, the small competitions and rivalries. If you can’t tell the truth about an era you witnessed and lived, you can’t tell the truth about anything. Initially my motivation was to tell the truth about that era, in some small way, by tracking one person’s life. As I did the research, I became more interested in Kathy’s writing. Reading it closely, understanding her process, I came to admire her in ways I hadn’t before.

CK: Richard Hell’s memoir, I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp, mentions Kathy in passing, a reference to some kinky-sex episode they had. And of course Richard wasn’t writing a book about Kathy, but I thought she deserved better than that. All of these memoirs and novels, photo exhibitions and films, were coming out about that era, the romance of the last avant-garde. And I found those depictions false. They necessarily edit out the texture of life: the boredom, the small competitions and rivalries. If you can’t tell the truth about an era you witnessed and lived, you can’t tell the truth about anything. Initially my motivation was to tell the truth about that era, in some small way, by tracking one person’s life. As I did the research, I became more interested in Kathy’s writing. Reading it closely, understanding her process, I came to admire her in ways I hadn’t before.

Do you think people will ever be done with New York? In a way, I think we’ve both tried, in our books, to finish with that romance.

When will people be done with New York?