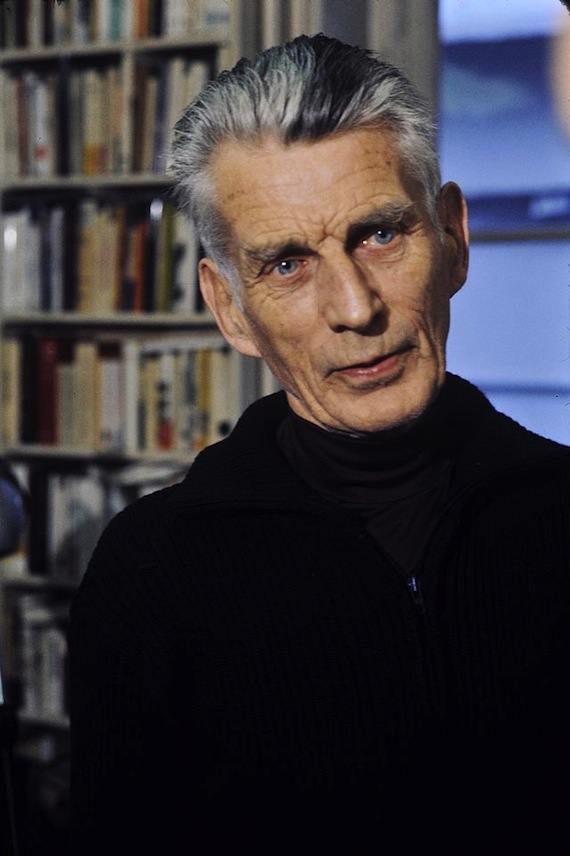

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Waiting for Godot’s English publication — Beckett’s self-translation of his original French play, En Attendant Godot, back into his native language. Godot was not Beckett’s first attempt at French composition; he had begun writing poetry in French as early as 1938 and translated Murphy into French in 1939. But Waiting for Godot was Beckett’s major foray into what would become his career-long routine of composing in French and self-translating into English. In the curious underworld of Beckettian translation studies, it’s a vexed topic. Some critics consider the doubled nature of Beckett’s oeuvre its distinguishing quality. Certainly, Beckett’s eccentric writing practice makes his bilingual corpus unique in the history of literature. But how do you classify self-translated texts? They eschew traditional categories, dwelling in some foggy realm between translation, revision, and authorial re-interpretation.

Then there’s the matter of priority: which text — French or English — emerges as the authoritative version? The English “translations,” written in Beckett’s native tongue, throw into question the “originality” of the original French texts. After all, don’t the French originals already imply the work of translation? Most scholars agree that the two versions of Godot should be studied side-by-side. In this way, any notion of priority is annulled, and the possibility of locating an “original” text, so central to our conceptions of artistic production, is all but swallowed by this black hole of textual duality.

Then there’s the matter of priority: which text — French or English — emerges as the authoritative version? The English “translations,” written in Beckett’s native tongue, throw into question the “originality” of the original French texts. After all, don’t the French originals already imply the work of translation? Most scholars agree that the two versions of Godot should be studied side-by-side. In this way, any notion of priority is annulled, and the possibility of locating an “original” text, so central to our conceptions of artistic production, is all but swallowed by this black hole of textual duality.

The key concern, though, is the question of motivation: Why did Beckett, an Irishman, choose to write in French and why, after achieving considerable success in that language, did he insist time and again on returning his work to the language of his homeland? Beckett himself provided a string of reflections on the issue. In a 1937 letter to his friend Axel Kaun, he explained,

It is becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothing-ness) behind it. Grammar and Style. To me they seem to have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit or the imperturbability of a true gentleman. A mask…Is there any reason why that terrible materiality of the word surface should not be capable of being dissolved?

Here Beckett expresses a desire to rid himself of the baggage of traditional English. Only by divesting himself of the “irrelevancies” of grammar and style, he thought, could he approach something like the truth beneath the “mask.” Since Beckett held such excessiveness and irrelevance of language to be endemic to English, he began experimenting with French, a language in which he claimed, “It is easier to write without style…[French] had the right weakening effect.”

This rejection of style figures, in a letter dated later that same year, as a sort of violence against language: “From time to time I have the consolation, as now [Beckett is writing in German], of sinning willy-nilly against a foreign language, as I should love to do with full knowledge and intent against my own — and as I shall do — Deo juvante.” What’s remarkable in these passages is the sense of desperation — indeed, of fervent compulsion — that drove Beckett to abandon his mother tongue. That English seemed to him “senseless” and “irrelevant,” a sort of falsity or façade that he felt compelled to “tear apart” and, finally, to “sin against,” throws Beckett’s bilingualism into a considerably darkened sphere. He wasn’t just playing around with language when he switched to French; the change marks neither an indulgence in the sport of interlingual word play, nor the disciplined resolve of a man fashioning himself a sort of writing exercise. Rather, the move from English to French was motivated by a fundamental necessity. It is as if Beckett required French for his very survival as a writer. Given the caliber of his early (English) work, it does not seem unreasonable, after all, to suggest that his status as literary genius is closely linked to his adoption of the French language.

But then, why was English unequal to Beckett’s aims? Part of the answer may lie in his relationship to James Joyce. Critics have cited their close friendship and Beckett’s perception of Joyce’s unparalleled achievements as the source of his need to escape English — to emerge from beneath Joyce’s shadow. There’s little doubt that Joyce’s legacy haunted; Beckett’s early work reveals an apish simulation of his mentor. A 1934 review of More Pricks than Kicks maintained, for instance, that Beckett “imitated everything in James Joyce — except the verbal magic and the inspiration…the whole book is a frank pastiche of the lighter, more satirical passages in Ulysses.” Beckett’s biographer, James Knowlson, also noted that Beckett’s 1932 novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, was “very Joycean in its ambition and its accumulative technique.” During this period, Beckett even mimicked Joyce’s research style, using dictionaries and reference books and weaving into his novel hundreds of quotations from other works of literature, philosophy, and theology. That his early style so closely resembled Joyce’s is hardly surprising; Beckett called Joyce’s work a “heroic achievement…that’s what it was, epic, heroic, what he achieved.”

But then, why was English unequal to Beckett’s aims? Part of the answer may lie in his relationship to James Joyce. Critics have cited their close friendship and Beckett’s perception of Joyce’s unparalleled achievements as the source of his need to escape English — to emerge from beneath Joyce’s shadow. There’s little doubt that Joyce’s legacy haunted; Beckett’s early work reveals an apish simulation of his mentor. A 1934 review of More Pricks than Kicks maintained, for instance, that Beckett “imitated everything in James Joyce — except the verbal magic and the inspiration…the whole book is a frank pastiche of the lighter, more satirical passages in Ulysses.” Beckett’s biographer, James Knowlson, also noted that Beckett’s 1932 novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, was “very Joycean in its ambition and its accumulative technique.” During this period, Beckett even mimicked Joyce’s research style, using dictionaries and reference books and weaving into his novel hundreds of quotations from other works of literature, philosophy, and theology. That his early style so closely resembled Joyce’s is hardly surprising; Beckett called Joyce’s work a “heroic achievement…that’s what it was, epic, heroic, what he achieved.”

Still, this seems a somewhat simple assessment. Joyce’s elaborate use of language stands in opposition to the minimalism Beckett sought, but Joycean prose can hardly be considered the language of traditional, highly-stylized English. In fact, disparate as their styles seem, Beckett and Joyce might be said to unite, in a manner, on the level of their reworking of the English language. If Beckett reached English through French, Joyce introduced the mother tongue to French, German, Italian, Latin, and other languages besides. In short, if Beckett’s reworking of English contrives to escape Joyce, it is an escape that simultaneously mimics him, for Joyce had already endeavored a great escape of sorts.

The genteel “gentleman’s” English that Beckett despised was more closely embodied by someone like Samuel Johnson, a literary figure of special interest to Beckett. He made a pilgrimage to Dr. Johnson’s birthplace, scrupulously perused the pages of Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, and filled his journals with notes on Johnson from which to compose a play. Though Beckett was fascinated by the man, he probably received his work somewhat differently: Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language and reputation as the authority on English letters easily rendered his name synonymous with the brand of English Beckett struggled to shake off. Of course, if English in Beckett’s mind was the language of Johnson, it was also the language, however refashioned, of Joyce. Sitting down to write in English, Beckett inevitably composed a Joycean English.

The genteel “gentleman’s” English that Beckett despised was more closely embodied by someone like Samuel Johnson, a literary figure of special interest to Beckett. He made a pilgrimage to Dr. Johnson’s birthplace, scrupulously perused the pages of Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, and filled his journals with notes on Johnson from which to compose a play. Though Beckett was fascinated by the man, he probably received his work somewhat differently: Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language and reputation as the authority on English letters easily rendered his name synonymous with the brand of English Beckett struggled to shake off. Of course, if English in Beckett’s mind was the language of Johnson, it was also the language, however refashioned, of Joyce. Sitting down to write in English, Beckett inevitably composed a Joycean English.

Beckett’s relation to his literary forefathers and to the English language — his near-violent desperation to do away with English and simultaneous adoration for Joyce’s work — is a case study in the complexities of literary influence. Harold Bloom (in The Anxiety of Influence) famously tried to de-idealize our notion of how one writer forms another — to refute the idea of literary creation as a carefree experience of muse-dappled inspiration and present it instead as an arduous, anxious, even diseased process: “Influence is influenza — an astral disease. If influence were health, who could write a poem? Health is stasis.” At once enraptured by his forefather’s work and nauseated by its effect on his own stunted writing, Beckett fled into a foreign tongue.

His is an unusual and extreme instance of poetic anxiety. Beckett didn’t just try to “get outside” his literary forefathers, which is how Bloom thinks most great writers produce original work. He tried to get outside even the language in which they wrote. In his adoption of French, Beckett may have recalled Joyce but he also rejected him. It wasn’t possible for him to innovate within the confines of the English tradition. He needed to rid himself of the language entirely — its echoes and associations — in order to open himself up to the potential for original artistic production. Beckett’s French texts — and, by extension, their English translations — are the result of this radical attempt to “get outside,” the anxiety of a writer infected not merely at the level of his forefather’s work, but at the level of the very language he employs.

Writing in French, Beckett adopted a new literary personality — a French life, a French set of texts, a French identity and reputation. It was his attempt to make a fresh start. But there is no clean slate on which to write, no mind wiped blank of history and influence — only the accumulation of voices, the last of which was his own. In En Attendant Godot and his other French texts, Beckett “sinned” (as he longed to do) against English and his literary forefathers. In Waiting for Godot and his English texts, he brought the sin home, facing down English — the language, the canon, Joyce, everything that had exiled him from his native tongue. Working through French, Beckett succeeded, finally, in writing himself into the English literary tradition.

He isn’t, in the end, strictly a writer or strictly a translator in any single work. Instead, Beckett’s texts collapse those identities, suggesting that authorship is always a matter of translation — the translation of experience into thought and thought into writing. His point in persistently translating his own work seems to have been to confuse us, to complicate the distinction between original and translation so that we are compelled to understand language generally as a kind of translation — and original texts as the consequence of texts that have come before: a vast lineage of influence and interpretation. Beckett just added a further leg to the journey, creating along the way twinned masterpieces in French and English.

Image Credit: Wikipedia