This August, not long before Labor Day, my wife and I packed the kids into the back of a rented car and left behind the garbage-smelling streets of New York for the comparative balm of Maine. For the second year running, we’d booked ourselves into a little bungalow about as far east as you can go before you drive into the ocean. This modest slice of paradise doesn’t come cheap; a week’s sublet costs only slightly less than our monthly rent. To my mind, though, it’s worth it — not least because the house’s sun porch is my favorite place to read in the entire world. There, with the kids napping upstairs and the porch’s old glass rippling the heavy-limbed spruces outside and the bees bumbling around in the hydrangeas and the occasional truck droning past on the two-lane, I can actually feel time passing. Moreover, I can choose to lavish a couple unbroken hours of it on a book, in a way life in the 21st-century metropolis (with small children!) renders vanishingly improbable.

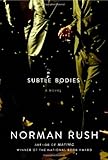

It’s no surprise, then, that many of my best reading experiences of the last year were concentrated in that single week. Early on, I read for the first time Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and found in the wry lushness of its prose a perfect literary analogue for the sensory assault of high summer in a new place. In fact, the divide between the life of the senses and the life of the mind is one of the many barriers Woolf’s intrepid hero/ine surmounts, “For it must be remembered that… [the Elizabethans] had none of our modern shame of book learning…no fancy that what we call ‘life’ and ‘reality’ are somehow connected with ignorance and brutality.” I then devoured, in the course of two naptimes, Norman Rush’s Subtle Bodies. Unlike its predecessors, Mating and Mortals, this novel has some glaring defects, and reviewers, by turns baffled and hostile, went straight for the invidious comparison. Yet what struck me was the through-line of Rush’s sensibility. The supreme pleasures of all of his work (the characters, the loving irony, the human comedy) are present here, in spades, and that made Subtle Bodies feel like a gift. And just before returning to New York, I read, in a state of admiration bordering on envy, the brilliant first third of Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers.

It’s no surprise, then, that many of my best reading experiences of the last year were concentrated in that single week. Early on, I read for the first time Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and found in the wry lushness of its prose a perfect literary analogue for the sensory assault of high summer in a new place. In fact, the divide between the life of the senses and the life of the mind is one of the many barriers Woolf’s intrepid hero/ine surmounts, “For it must be remembered that… [the Elizabethans] had none of our modern shame of book learning…no fancy that what we call ‘life’ and ‘reality’ are somehow connected with ignorance and brutality.” I then devoured, in the course of two naptimes, Norman Rush’s Subtle Bodies. Unlike its predecessors, Mating and Mortals, this novel has some glaring defects, and reviewers, by turns baffled and hostile, went straight for the invidious comparison. Yet what struck me was the through-line of Rush’s sensibility. The supreme pleasures of all of his work (the characters, the loving irony, the human comedy) are present here, in spades, and that made Subtle Bodies feel like a gift. And just before returning to New York, I read, in a state of admiration bordering on envy, the brilliant first third of Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers.

Probably the single most perfect book I encountered in 2013, though, appeared under completely different circumstances — that is, in February, back in the city, amid the ice. Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives didn’t just reward my attention; it commanded it. To pick up the book was to be summoned away from the diced-up jumble of my own unfinished errands and brought into the presence of Anna and Melanctha and Lena. Reading Stein is like being brainwashed, but in a positive sense. It cleanses the windows of perception. It is Maine on the page.

Probably the single most perfect book I encountered in 2013, though, appeared under completely different circumstances — that is, in February, back in the city, amid the ice. Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives didn’t just reward my attention; it commanded it. To pick up the book was to be summoned away from the diced-up jumble of my own unfinished errands and brought into the presence of Anna and Melanctha and Lena. Reading Stein is like being brainwashed, but in a positive sense. It cleanses the windows of perception. It is Maine on the page.

In fact, much of what moved me most in 2013 drew in one way or another on the Modernist legacy of “deep time,” a countervailing force to the jump-cut, the click-through, the sample rate. I came to the reissue of Renata Adler’s Pitch Dark, for example, expecting a kind of cool PoMo minimalism. Instead, I discovered a crypto-maximalist whose sentences, surfing along on volumes of unexpressed pain, are as perfect in their way as Woolf’s. Péter Nádas’s putatively maximalist Parallel Stories, meanwhile, offered the most miniaturist reckoning of behavioral psychology this side of…well, of Gertrude Stein. The erotic excesses everyone complains about — e.g, the 300-page sex scene — are in fact the opposite of erotic; they’re a kind of clinical accounting of the physical side of human history, the flesh that has a mind of its own. “Unsubtle Bodies,” would have been a good title. But in the end, I respected the hell out of Parallel Stories, and ended up despite myself — despite, perhaps, even Nádas — caring deeply about its characters. And then there was Laszlo Krasznahorkai. Where his first three novels to appear in English were dark, his latest, Seiobo There Below, is bright. Where they were terrestrial, it is astral. But in one important respect, it’s just like them: it’s a masterpiece.

In fact, much of what moved me most in 2013 drew in one way or another on the Modernist legacy of “deep time,” a countervailing force to the jump-cut, the click-through, the sample rate. I came to the reissue of Renata Adler’s Pitch Dark, for example, expecting a kind of cool PoMo minimalism. Instead, I discovered a crypto-maximalist whose sentences, surfing along on volumes of unexpressed pain, are as perfect in their way as Woolf’s. Péter Nádas’s putatively maximalist Parallel Stories, meanwhile, offered the most miniaturist reckoning of behavioral psychology this side of…well, of Gertrude Stein. The erotic excesses everyone complains about — e.g, the 300-page sex scene — are in fact the opposite of erotic; they’re a kind of clinical accounting of the physical side of human history, the flesh that has a mind of its own. “Unsubtle Bodies,” would have been a good title. But in the end, I respected the hell out of Parallel Stories, and ended up despite myself — despite, perhaps, even Nádas — caring deeply about its characters. And then there was Laszlo Krasznahorkai. Where his first three novels to appear in English were dark, his latest, Seiobo There Below, is bright. Where they were terrestrial, it is astral. But in one important respect, it’s just like them: it’s a masterpiece.

I know I tend to go on about the Hungarians, but this seemed to be a ridiculously rich year for American fiction, too. Fall, in particular, was a murderer’s row of big books; I could talk here about Lethem, about Tartt, about Pynchon, about David Gilbert, about Caleb Crain, about James McBride’s surprise National Book Award, but I’d like to put in a good word for a couple of books that came out in the early part of the year, and were perhaps overlooked. The first is William H. Gass’s Middle C. Not only hasn’t Gass lost a step at age 88; he’s gained a register. One of Middle C’s deep motifs involves an “Inhumanity Museum,” but the surface here is warmer and funnier and more approachable than anything Gass has written since Omensetter’s Luck.

I know I tend to go on about the Hungarians, but this seemed to be a ridiculously rich year for American fiction, too. Fall, in particular, was a murderer’s row of big books; I could talk here about Lethem, about Tartt, about Pynchon, about David Gilbert, about Caleb Crain, about James McBride’s surprise National Book Award, but I’d like to put in a good word for a couple of books that came out in the early part of the year, and were perhaps overlooked. The first is William H. Gass’s Middle C. Not only hasn’t Gass lost a step at age 88; he’s gained a register. One of Middle C’s deep motifs involves an “Inhumanity Museum,” but the surface here is warmer and funnier and more approachable than anything Gass has written since Omensetter’s Luck.

Fewer readers will have heard of Jonathan Callahan, whose first book, The Consummation of Dirk, was published in April by Starcherone Press. It’s a multifariously ambitious story collection on the model of David Foster Wallace’s Girl With Curious Hair. The glaring debts to Wallace and Krasznahorkai and Thomas Bernhard can be a liability, but in the longer stories here, including “A Gift” and “Cymbalta” and “Bob,” and in the closing trio, Callahan uses the pressure of influence to form shapes entirely his own.

Fewer readers will have heard of Jonathan Callahan, whose first book, The Consummation of Dirk, was published in April by Starcherone Press. It’s a multifariously ambitious story collection on the model of David Foster Wallace’s Girl With Curious Hair. The glaring debts to Wallace and Krasznahorkai and Thomas Bernhard can be a liability, but in the longer stories here, including “A Gift” and “Cymbalta” and “Bob,” and in the closing trio, Callahan uses the pressure of influence to form shapes entirely his own.

On the poetry side, I adored Bernadette Mayer’s rousing and funny collection, The Helens of Troy, New York. Meyer uses various quasi-Oulipian formal constraints to turn interviews with the titular Helens — yes, every woman named Helen living in Troy, New York — into poems. Both Helens and Troy emerge richer for the transformation. And while Patti Smith’s Just Kids isn’t technically verse, it makes good on every claim for Smith as one of the few true rock n’ roll poets. (The late Lou Reed was another.) Not only is Just Kids an unmissable story; it attains the same purity of expression as Horses.

On the poetry side, I adored Bernadette Mayer’s rousing and funny collection, The Helens of Troy, New York. Meyer uses various quasi-Oulipian formal constraints to turn interviews with the titular Helens — yes, every woman named Helen living in Troy, New York — into poems. Both Helens and Troy emerge richer for the transformation. And while Patti Smith’s Just Kids isn’t technically verse, it makes good on every claim for Smith as one of the few true rock n’ roll poets. (The late Lou Reed was another.) Not only is Just Kids an unmissable story; it attains the same purity of expression as Horses.

Usually, rock writing is a kind of guilty pleasure. Unforgettable Fire, Glory Days… I feel absolutely no guilt, though, in recommending the English journalist Nick Kent’s collection of rock profiles, The Dark Stuff. It’s John Jeremiah Sullivan good. Gay Talese good. Sometimes it’s even Joseph Mitchell good.

I made it through a couple of other great works of narrative journalism this year, as well. William Finnegan, in addition to being one of my favorite New Yorker writers, has got to be one of the best reporters on earth, and his Cold New World, published in 1998, is like a Clinton-era companion to George Packer’s The Unwinding. In it, Finnegan spends months with teenagers in four far-flung American communities, uncovering the frictions of the new economy long before it blew up in our faces. Robert Kolker’s The Lost Girls, which came out this summer, similarly examines the effect of those frictions on young women drawn into prostitution — specifically, five young women who would end up murdered by a serial killer out on Long Island. Kolker doesn’t turn phrases with the acuity of Kent or Finnegan, but his patient unfolding of his story gives the reader room to become outraged.

I made it through a couple of other great works of narrative journalism this year, as well. William Finnegan, in addition to being one of my favorite New Yorker writers, has got to be one of the best reporters on earth, and his Cold New World, published in 1998, is like a Clinton-era companion to George Packer’s The Unwinding. In it, Finnegan spends months with teenagers in four far-flung American communities, uncovering the frictions of the new economy long before it blew up in our faces. Robert Kolker’s The Lost Girls, which came out this summer, similarly examines the effect of those frictions on young women drawn into prostitution — specifically, five young women who would end up murdered by a serial killer out on Long Island. Kolker doesn’t turn phrases with the acuity of Kent or Finnegan, but his patient unfolding of his story gives the reader room to become outraged.

As usual, I find myself running on well beyond “Year in Reading” length. But in my defense: I hardly reviewed anything this year! This is my one chance to enthuse! And though I’ve talked about William Gass, and William Finnegan, what about William Styron’s The Long March, or William T. Vollmann’s Fathers & Crows? This is not to mention The Luminaries, which is currently sitting half-read on my nightstand, alongside The Cuckoo’s Calling and The Bridge Over the Neroch and Teju Cole. My wife says it’s starting to look like a hoarder lives here. How am I ever going to finish all this stuff? But I remain optimistic, against all the evidence, that life might offer a little more time to read in 2014. And if not, I suppose we’ll always have Maine.

As usual, I find myself running on well beyond “Year in Reading” length. But in my defense: I hardly reviewed anything this year! This is my one chance to enthuse! And though I’ve talked about William Gass, and William Finnegan, what about William Styron’s The Long March, or William T. Vollmann’s Fathers & Crows? This is not to mention The Luminaries, which is currently sitting half-read on my nightstand, alongside The Cuckoo’s Calling and The Bridge Over the Neroch and Teju Cole. My wife says it’s starting to look like a hoarder lives here. How am I ever going to finish all this stuff? But I remain optimistic, against all the evidence, that life might offer a little more time to read in 2014. And if not, I suppose we’ll always have Maine.

More from A Year in Reading 2013

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.