My dictionary is the sturdy, hardback two-volume edition of The New Shorter Oxford English much loved by editors the world over – even if they have to keep it on the bottom shelf so the bookcase doesn’t topple over. Although it’s an effort to pull it out and I’m always concerned about a possible hernia or crushing my dozing cat in the event of a misstep during transit, there is no way in Hades I will ever use an online version. Nothing beats the individually carved furrows for each letter of the alphabet, the “looking up” process that my print version permits. I do not want or need to know the meaning of a word instantly. I enjoy the minor workout my mind receives in scanning the page, calculating if I need to flip forward or turn back in order to finally, satisfyingly arrive at my destination. Such pleasure is usually diminished by the brand of “ever so pleased with itself” fiction that clubs you over the head as many times as possible in each sentence with mysterious words that do little more than highlight the author’s need to prove he is much smarter than the you. John Banville, I’m looking at you here. Like most people, I don’t wish to feel moronic when reading, even if it is uncomfortably close to the truth.

This is part of what made Aleksandar Hemon’s Love and Obstacles such a revelatory reading experience. Yes, he used words I’d never heard of, and once I had hired a crane to lug my dictionary to the table, it stayed there. In fact, I felt like such an idiot I started looking up words I thought I knew the meaning of, only to discover that I had often been sorely mistaken. Let me throw a few examples at you, see how you fare. Fenestral. No? What about edentate? Numinous? Yet Hemon is no show-off who ate the OED for breakfast. He evidently loves the dictionary, but keeps his language simple and straightforward, with these fabulous words thrown in occasionally, giving the impression he has only just discovered them himself and is reveling in sharing them with you.

This is part of what made Aleksandar Hemon’s Love and Obstacles such a revelatory reading experience. Yes, he used words I’d never heard of, and once I had hired a crane to lug my dictionary to the table, it stayed there. In fact, I felt like such an idiot I started looking up words I thought I knew the meaning of, only to discover that I had often been sorely mistaken. Let me throw a few examples at you, see how you fare. Fenestral. No? What about edentate? Numinous? Yet Hemon is no show-off who ate the OED for breakfast. He evidently loves the dictionary, but keeps his language simple and straightforward, with these fabulous words thrown in occasionally, giving the impression he has only just discovered them himself and is reveling in sharing them with you.

This glee in the English language stems from the fact that in 1992, at age 28, Hemon was stranded in Chicago when war broke out in his native Bosnia. His fiction is replete with mentions of how fortunate he was not to be in Sarajevo at the time, but tinged with regret that he will never understand the conflict that tore his country apart as well as someone who was there. Hemon had already written several stories in his native language but only began writing in English upon his absorption into American culture. Unable to return to his homeland, Hemon worked as a bike messenger, a doorknocker for Greenpeace, in a bookstore, and eventually as an ESL teacher.

His English language stories began to appear in American literary journals in 1995, and by 1999 he had his first piece picked up by The New Yorker. Naturally a collection of his early stories followed a year later, The Question of Bruno. No less a talent than Zadie Smith ruefully commented, “The Question of Bruno is all right I suppose if you appreciate multilingual genius types who learn the language in six months, write with great humour and style and then get compared to Nabokov in the New York Times.”

His English language stories began to appear in American literary journals in 1995, and by 1999 he had his first piece picked up by The New Yorker. Naturally a collection of his early stories followed a year later, The Question of Bruno. No less a talent than Zadie Smith ruefully commented, “The Question of Bruno is all right I suppose if you appreciate multilingual genius types who learn the language in six months, write with great humour and style and then get compared to Nabokov in the New York Times.”

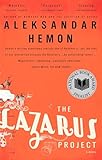

A novel, Nowhere Man, featuring one of his earlier characters, Jozef Pronek, came out to considerable acclaim in 2002 but it was a 2004 genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation that marked a dramatic upswing in his career. Half a million dollars in his pocket meant Hemon was able to travel back to Sarajevo with his childhood friend, the photographer Velibor Bozovic to research his superb 2008 novel, The Lazarus Project. This investigation into the real-life 1908 murder of Jewish immigrant Lazarus Averbuch by Chicago’s then Chief of Police, George Shippy, is illustrated with Bozovic’s photography and is a telling meditation on the life of a migrant. One year after its release, Hemon’s most recent book of short stories, the aforementioned Love and Obstacles, appeared.

A novel, Nowhere Man, featuring one of his earlier characters, Jozef Pronek, came out to considerable acclaim in 2002 but it was a 2004 genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation that marked a dramatic upswing in his career. Half a million dollars in his pocket meant Hemon was able to travel back to Sarajevo with his childhood friend, the photographer Velibor Bozovic to research his superb 2008 novel, The Lazarus Project. This investigation into the real-life 1908 murder of Jewish immigrant Lazarus Averbuch by Chicago’s then Chief of Police, George Shippy, is illustrated with Bozovic’s photography and is a telling meditation on the life of a migrant. One year after its release, Hemon’s most recent book of short stories, the aforementioned Love and Obstacles, appeared.

The question of how a writer manages to express himself so well in a language that is not his own and in such a short space of time is perhaps a puzzling one, but Zadie Smith hints at the answer in her summation of his first collection. Hemon taught himself English by reading Nabokov’s Lolita—an insanely daunting task. In a 2008 interview with the Guardian, Hemon explained,

I didn’t know half the words. At the beginning I would start underlining the words I didn’t know on the page, but then I started underlining too many, so I started writing them out on notecards, and whenever I read, I made lists of words and then looked them up in the dictionary.

It’s a technique Nabokov probably would have appreciated, given that he drafted his novels on index cards. (His most recent posthumous publication, The Original of Laura, is in fact presented as a series of perforated index cards, designed to be removed and shuffled by the reader, even if it is difficult to imagine philistines tearing apart Chip Kidd’s design.)

“Lolita is the bomb,” Hemon told the Guardian. Reading it in English after reading it in translation “was like the difference between listening to an orchestra live and through a phone.” Applying Nabokov’s love of English to his own work caused some ire among reviewers at first, who felt that beneath the startling words lay an understanding of grammar and diction that left something to be desired. But Hemon, who has stated in several interviews that he speaks much better English than he does Bosnian, wanted to embrace Nabokov’s willingness to experiment with language. In a 2008 interview with BOMB magazine, he said that during the ESL classes he taught, he would identify the roots of certain English words in the home countries of his students, thus allowing them to lose their fear of the world language. “The thing with English,” he suggested,

is that its borders can be pushed. It can be transformed and recharged. At the same time, because it is so fluid, so limitless, people feel that the rules and idiomatic strictness must be enforced – otherwise the foreigners will take the language away.

This defiant ‘owning’ of English is evident throughout Hemon’s work. As a Bosnian writing in English he feels none of the trepidation most non-English writers do about “getting it wrong.” Released from such constrictions, his prose is natural and flowing, peppered with rich, satisfying phrases. A slug in the rain is described so: “The wet dew on its back twinkled: it looked like a severed tongue.” A “wet loaf of bread” is seen to have “excited ants crawling all over it, as if building a pyramid.” The ass of a horse taking a poop opens slowly, “like a camera aperture.”

Hemon is also unafraid of inserting himself into his narratives, albeit in a heavily disguised and exaggerated form. His protagonists are often Bosnian men living in Chicago, despite his abhorrence of “the memoir craze,” as he puts it. “I hate it beyond words. It’s a crisis of the imagination.” Hemon cleverly deflected any criticism of his seemingly autobiographical stories in an interview with The New Yorker last year. He describes hurting the ligament in his hand one morning and losing control of his car while talking on the phone with his sister in London. He sideswipes his neighbor’s parked car and knocks on their door to confess. When no one answers and he notices the door is unlocked, he ventures inside to see if they are home. In the living room he spots a strange vase in the shape of a monkey head and picks it up for a closer look. His injured ligament lets him down and he drops the vase, smashing it. Now mortified, he scurries out of the house with the new intention of admitting nothing.

This sounds like a perfect Hemon short story, except he then admits that he did not actually call his sister, though she does live in London. He caused no damage, did not trespass and saw no monkey-head vase. The only parts of the tale that actually happened were that he hurt his hand one morning and still drove his car. Yet such is Hemon’s mastery of language that even a casual recounting of the story during an interview is compelling enough to be believable.

Hemon has built his own version of English. It is fluid and clever, refreshingly free of the jarring attempts to dazzle the reader often found in contemporary literary fiction. He is the first writer I have read who made me wish I could forget all the bad habits and lazy tics ingrained through virtue of being born a native English speaker, that I could start again from scratch and build a formidable lexicon such as his – simple, elegant and imbued with a profound love for the beauty of forgotten words.