In mid-September, the EPSN host Jemele Hill tweeted an entirely reasonable series of statements including “Donald Trump is a white supremacist who has largely surrounded himself w/ other white supremacists,” and “Trump is the most ignorant, offensive president of my lifetime. His rise is a direct result of white supremacy. Period.” In response to the ensuing backlash, The New York Times ran an op-ed titled “Is Trump a White Supremacist?”

In the piece, Charles M. Blow writes, “If you are not completely opposed to white supremacy, you are quietly supporting it,” concluding: “Either Trump is himself a white supremacist or he is a fan and defender of white supremacists, and I quite honestly am unable to separate the two designations.”

While Blow offers a thoughtful assessment of Trump’s white supremacism, the fact that the piece’s central question—a query vaguely akin to “Should I Accept Anthony Weiner’s Friend Request on Snapchat?”—needed to be asked in the first place indicates that we’ve officially descended into some surreal, fake-news hellscape where every red-blooded American can choose between facts and alternate facts, attend a lecture by Harvard Fellow Sean Spicer, and wait for the next Official Donald J. Trump Big League Box of the Month to arrive via a privatized U.S. Postal Service.

To state the obvious:

- If you want to build a wall on the Mexican border to keep out all the “rapists,” you’re a white supremacist.

- If Jeff Sessions is your Attorney General, you’re a white supremacist.

- If David Duke enthusiastically endorsed your presidential candidacy, you’re a white supremacist.

- If you think “some very fine people” attended the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, you’re a white supremacist.

- If you pardon Joe Arpaio and call him “an American patriot,” you’re a white supremacist.

- If you want to ban Muslims from entering the United States, you’re a white supremacist.

And if you support a president who does those things, that makes you a white supremacist, too. Of course, supporting/being white supremacists isn’t something large segments of the American public has ever really had a problem with.

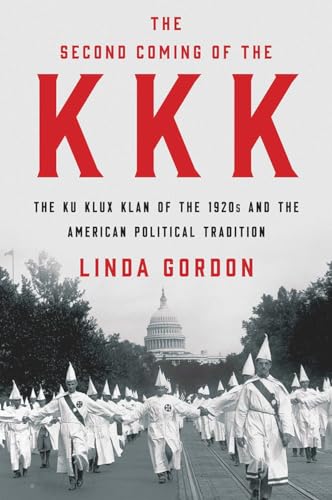

In her latest book, The Second Coming of the KKK, historian Linda Gordon charts the rise of the reconstituted Klan—which at the height of its power in the 1920s boasted some 6 million members, including 16 senators, scores of congressmen, and 11 governors. The book not only offers a look back at how the hate group achieved unparalleled mainstream success, but also shines a light on our current political moment and the man who won the White House in 2016.

The Millions chatted with Gordon recently by phone about bigoted feminism, the evil fusion of racism and religion, how the media misrepresents the women’s movement, and the future of hate groups in Trump’s America.

The Millions: As I read the book, I was struck by the similarities between the tactics of the Klan of the 1920s and those of the alt-right and Donald Trump. Things like saying immigrants are taking jobs, blaming minorities for crime, fear about the collapse of law and order. In what ways do you see these two movements as similar or different?

Linda Gordon: As a preface, I would say I decided very deliberately not to mention Trump, Trumpism, the alt-right, or anything contemporary in the book. Partly because I figured people would see these things themselves. And I wanted to retain my commitment to evidence. But the similarities are extraordinary. One is bigotry; another is the use of conspiracy theory. And conspiracy theory is very closely related to fake news because one of the advantages of conspiracy theories is that you can explain away the fact that there is no evidence for your claim as a kind of circularity. That because conspiracies are secret, of course there is no evidence.

There is also something that is characteristic of only a very small part of the alt-right today. One of the Klan’s most brilliant moves was to fuse religion with bigotry. That was absolutely not characteristic of the first Klan with its terrorism and lynching. The choice to do that was extremely strategic and instrumental. In other words, to bring in a kind of evangelical notion that is related to the claim that America had a destiny—a destiny anointed by God to be a white Nordic Protestant nation.

TM: You identify six “ancestors” that contributed to the ‘20s Klan’s makeup: racism, nativism, temperance, fraternalism, Christian evangelicalism, and populism. Of those six, it seems maybe temperance and fraternalism are less relevant today. How have the six pillars aged since the 1920s?

LG: The temperance issue is more or less dead. I don’t think that you’re going to get traction from a prohibitionist point of view today. Although it may be related to people who have prohibitionist attitudes about drugs. The issue of fraternalism is a little bit more complicated because by fraternalism we can mean certain kinds of fraternal organizations. And over time, those organizations—the Elks, the Masons—they still exist, but they’ve lost ground to organizations that are more like Rotary Clubs, that are organizations designed to benefit people through networking.

But, by fraternalism you can also mean the construction of the kinds of bonds that were once called brotherhood, which I think are really important to all social movements, whether on the left or the right. And one of the satisfactions of participating in a social movement is that very close feeling of brotherhood with other people.

One of the things that’s a little different about that today, though, is that in many situations, like what happened in Charleston, the fraternalism of the white nationalists works by their sense that they are the persecuted minority.

TM: That seems like something that the Klan of the ‘20s did to great success?

LG: Exactly. And, they did it despite the fact—I think it is arguably the case—that the majority of white Protestant Americans would have agreed with the Klan’s basic principles, and it may be that they differed only in terms of the intensity of the way they wanted to promote those ideas.

Whereas today I do think—and this is a little bit reassuring—that the alt-right remains a minority; that we do have a pretty solid majority of Americans who want to reject that kind of revving up of racist anger.

TM: You devoted a chapter to the women of the Klan—many of whom could be described as feminists, and without whom the Klan of the ‘20s would’ve been much less powerful and less successful. But you describe it as a “bigoted feminism.” And you write, people “must rid themselves of the notions that women’s politics are always kinder, gentler, and less racist than men’s.” That made me think of the large percentage of white women who voted for Trump, which surprised a lot of people. Not to equate female Trump voters with Klanswomen, but what parallels do you see between those two groups.

LG: If I have any anxiety about people being offended by the book, it will have to do with that chapter because there are many people, including people I know and love, who want to think that you have to define feminism as a progressive, antiracist issue—and that any other claims are just not really feminism.

Whereas my preference is to say, well, unfortunately, it’s not up to us to define feminism and that we have to use it in a generic sense in which anyone who is after greater rights for women or greater sex equality can be called a feminist. But I think that Klan feminism does illustrate something very important about the support that so many women gave to Trump, and that is that we cannot assume that women’s concerns with gender issues are always their prominent concerns—their most prominent concerns.

In the ‘20s, once the women’s suffrage amendment passed, the Klan supported it energetically. They thought they’d get more votes that way. But today, I think there is a lot of resentment against the fairly powerful women’s movement that arose in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. I think that resentment has two different sources.

One, I would argue, as someone who’s taught and studied social movements, that almost no social movement has been as misrepresented by the media as the women’s movement. Misrepresented in the direction of focusing almost exclusively on sex and reproduction issues. Sexual freedom, abortion, support for gay and transgender rights. The coverage usually neglected issues that just may not seem as newsworthy, like the enormous energy put into campaigns for subsidized childcare, for paid parental leave, for equal access to jobs and promotions. What you might call the more base economic issues. And those include campaigning for things that benefit women who are not employed as well as for women who are employed.

I also think that, like it or not, we have to face the fact that some of the more prominent people, groups, and energy behind contemporary feminism comes from a more professional class. Highly educated women who often, just as men of that class do, speak rather disdainfully of people who don’t agree with them. And that leads to another point that I think is problematic today—and that is the way that people who are on the liberal side speak of people who are more sympathetic to the Trump side. And that is to speak of them very disdainfully—Oh, how can they be so dumb? How can they be so ignorant as to believe these things and to be taken in by these lies?

That’s not only not productive, but it’s also not correct. One of the things we know from the polls is that very large numbers of very prosperous and very well-educated people supported Trump. I don’t think that lack of smarts can explain that phenomenon.

TM: To turn back to the ‘20s Klan, that second incarnation was much more successful than the first and third, at least in terms of membership. And probably more successful than any other hate group in U.S. history. What do you attribute that success to?

LG: At base, the success came from broadening the repertoire of who were the targets, of who were the bad guys. So a lot of people could be pulled in. Part of the reason they went that way is that something built strictly on anti-black racism would not have had traction in the ‘20s in the North because there were so few African-Americans living in the North.

In a lot of places of the core Klan strength— say, Indiana—people probably had never seen a Mexican-American and had never seen an Asian-American. So, the Klan was very effective in adapting to local issues. In the State of Washington, they were very focused on anti-Japanese bigotry.

You have to keep in mind another aspect of the Klan—that it became very big, but it also declined very fast. And people who have been able to look closely at some of the actual records of memberships and collection of dues have found that there was tremendous turnover. People got drawn in and lost interest. Now, partly it was because belonging to that Klan was pretty expensive, and partly it was because people just got tired of one part of what attracted them, which is all this kind of arcane hocus-pocus ritual that at first seemed like entertainment.

But you also have to consider the background of the so-called opposition. Between the ‘20s and today, we do have a much stronger consensus around civil liberties, around antidiscrimination—at least hostilely to legal discrimination. The whole country has moved closer toward an acceptance of what you might call a liberal democratic perspective, as opposed to the Klan’s democracy for the “right people.”

One major difference is that today’s Klan is completely decentralized. There is no Imperial Wizard who can command the allegiance of people and can head what was really a giant moneymaking machine. That’s not the case today. Possibly people today are a little more of the view that social movements should be separate from profitmaking enterprises.

TM: The success the Klan had in the ‘20s, do you think that could ever be replicated by a similar hate group today?

LG: I would never say never. I would never rule out anything. We have seen the way in which American foreign policy ventures can rev up a tremendous spirit of patriotism, and the notion that if you don’t support them you’re not a good American. It was three decades after the Klan that we saw the enormous impact of McCarthyism and its ability not just to persecute a relatively small number of people—but that persecution functioned in a manner that was designed to be intimidating to masses of people. It certainly made lots of people more reluctant to speak out and willing to assume that anything that was being labeled as un-American or unpatriotic was something they should not even bother to find out about.

TM: Based on your study of the success of the Klan from the ‘20s, what lessons should people committed to fighting hate and racism take away from that period of history?

LG: One really important takeaway is that bigotry is all of a piece. You can’t be antiracist if you’re not also anti-anti-Semitic. There are a number of reasons for that. One is it all comes from the same place in the psyche, that is an inclination to direct your anger downward rather than upward.

Another feeling that I have—though it doesn’t precisely come from my work on the Klan; it comes perhaps from a little bit of anxiety I have at some of the responses to the alt-right—is that trying to fight them on their own terms is a mistake. I probably lean toward almost 100 percent passivism. I really dislike violence unless it’s absolutely a last defensive resort. I’m a little disturbed by the rise of these antifa groups. We have to remain clear about our commitment to freedom of speech, but at the same time about the enormous importance of standing up against these ideas in every possible nonviolent way.

One of the problems in social movements on the liberal side in the last 30 to 40 years is that a lot of what used to be social movements have really become professional organizations. So, for example, NARAL, which I certainly support. What they want of me is simple: they want a contribution. That’s all they want from me. One of the geniuses of the Klan and of many social movements is that they ask people to do something, not just to contribute money… Some of the most successful [social movements] are those that literally demanded a certain level of active participation and basically communicated that you’re not a member of this unless you actually participate. Invoking a little discipline on members. That was very, very characteristic of the Civil Rights Movement and very much behind some of its victories.

We can’t defeat these kinds of things simply by giving money to professional lobbying groups. They’re extremely important. I don’t want to denigrate them in any way. But people have to be prepared to do more. And one of the hopeful signs is that people have gone to anti-Trump demonstrations that have never demonstrated before.

TM: What does America need to do to survive Donald Trump?

LG: One of the worst problems that we face is not Trump himself, but the relative unwillingness of any Republicans to really break with him, because their allegiance is, above all, to the votes they think that kind of thing can produce.

I love all the comedians that make fun of Donald Trump. He’s a very easy target. One of the problems in that—and the focus on the Russia connection—is it takes people’s attention [away from] what is going on underneath. The deregulation of everything, the giving away of the National Parks, the deregulation of Wall Street, the stripping of the environmental safety regulations.

So, one thing we could do, is to try to keep the focus on policy—on what is actually being changed in the Constitution and the network of laws that we have in this country that do what government is supposed to do, which is to protect us.