“Private letter to you,” wrote Ernest Hemingway to Archibald MacLeish on December 1, 1929. Two months earlier, he’d followed the success of The Sun Also Rises with his breakout, bestselling work, A Farewell to Arms. In the Richmond Times-Dispatch, James Aswell wrote that upon finishing the book, he is “still a bit breathless, as people often are after a major event in their lives. If before I die I have three more literary experiences as sharp and exciting and terrible as the one I have just been through, I shall know it has been a good world.”

But Hemingway was a writer, and writers work. We toil, we dream, we fail, we hope. He was living in Paris with his wife, Pauline, their two children, and Hemingway’s younger sister, Madelaine. His father, Dr. Clarence E. Hemingway, had committed suicide a year earlier, and Hemingway had established a trust fund for his mother and his younger siblings. MacLeish had just been hired as an editor of the recently debuted magazine Fortune, and Hemingway wanted to talk money.

But Hemingway was a writer, and writers work. We toil, we dream, we fail, we hope. He was living in Paris with his wife, Pauline, their two children, and Hemingway’s younger sister, Madelaine. His father, Dr. Clarence E. Hemingway, had committed suicide a year earlier, and Hemingway had established a trust fund for his mother and his younger siblings. MacLeish had just been hired as an editor of the recently debuted magazine Fortune, and Hemingway wanted to talk money.

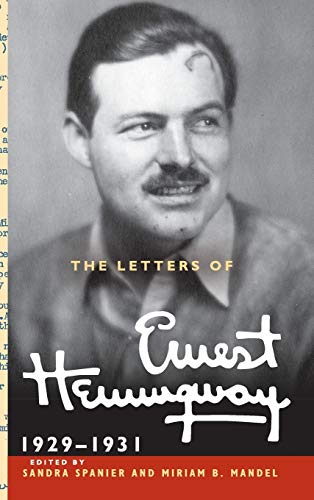

The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: 1929-1931 are the fourth volume of his correspondence, and nearly 85 percent of them are being published for the first time. The result is a windfall for Hemingway fans, but also for those trying to understand the daily working life of a major writer—about whom biographer Michael S. Reynolds notes “His contemplative and his active life are jammed together so tightly that only minutes separate them.”

Editors Sandra Spanier and Miriam B. Mandel are comprehensive and meticulous in their approach—the book is peppered with contextual footnotes that moor the letters—and the result is real insight into a stubborn, driven, accomplished writer. Although the letters document his life as an outdoorsman, as well as his fracturing friendship with F. Scott Fitzgerald, the correspondence best illuminates his life as a writer.

“You know how I hate to pull money terms etc. with you,” writes Hemingway to MacLeish, before promptly talking about money. He quotes offers from Collier’s Weekly—$750 for 1000-1200 word stories—so he wants at least $2000 for the long article on the economics of bullfighting in Spain. “I would write it for you for nothing,” he promises, but knows “I have to keep the price up because thats how they judge you.”

Hemingway’s article would be published the following year as “Bullfighting, Sport and Industry,” and would later become part of his first bullfighting book, Death in the Afternoon. A Farewell to Arms would soon be translated into French and German, and become a Broadway play. Hemingway also sold the film rights, although he hated the film version, starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes.

The business of being a writer is a business, and Hemingway’s letters demonstrate that even the most celebrated writers encounter countless setbacks. Writing is a struggle. Publishing is a struggle. It is fine to accept that. Writing is wonderful, it is cathartic, it is frustrating. The pulse of writing is paradox. Poets know this in their lines; freelancers know this when they sit down to pitch.

Hemingway’s letters allow us to follow that trail of failures and successes, and how a writer’s life off the page affects their words. In a 1931 letter to Dr. Don Carlos Guffey, a fervent collector of Hemingway’s books who would deliver Hemingway’s son Gregory later that year, Hemingway sounds rushed, nervous, and afraid. He will soon be off to Spain, and has a request of the doctor:

“In case anything should happen to me—in the bull ring or any other dumb way—I have told Pauline where to find the copy of the 3 Stories and 10 poems that it is to go to you—Do not expect any disasters nor have any premonitions but have had so many accidents lately that should take that step to protect your interests.”

Hemingway laments the paltry money he’d made from In Our Time, and how he couldn’t sell a single story from the collection to a magazine. His final words in the letter about the writing life were true in 1931, and will be true for eternity: “It is a strange business.”