At our house, we ate dinner around 5:30, and talk of the apocalypse typically began by 6:15. Between food and the end of the world, I had no particular preference. I looked forward to both. My family was big on mashed potatoes and iceberg lettuce, which was the only kind of lettuce we knew about back in 1981, and we were big on togetherness. We prayed aloud before dinner, holding hands around the dining room table, and we read books aloud afterward, sitting in the adjacent living room. This reading tradition lasted several years, and its star author was a man named Salem Kirban, whose most famous books were titled 666 and 1000.

He’s little talked about today, but Kirban’s books were the original evangelical “end times” books. 666 came out in 1970, and 1000 followed in 1973. Both were bestsellers, and you’d find these paperbacks in households like mine. These were basically horror stories for Christians. Kirban was the Stephen King for apocalyptically savvy evangelicals who weren’t allowed to read the real King.

He’s little talked about today, but Kirban’s books were the original evangelical “end times” books. 666 came out in 1970, and 1000 followed in 1973. Both were bestsellers, and you’d find these paperbacks in households like mine. These were basically horror stories for Christians. Kirban was the Stephen King for apocalyptically savvy evangelicals who weren’t allowed to read the real King.

Kirban set the trend of framing the rapture in fiction, and his sensationalist bent got more Christians to hear the apocalyptic clock ticking. In the mid-’90s, this view of the apocalypse would be further popularized by the Left Behind novels. When many of the evangelicals who now follow Donald Trump look to the end of the world, what they’re picturing isn’t far from Kirban’s version. (Well, except maybe for the guillotines on church lawns.)

Salem Kirban himself remains something of a mysterious figure. In one photo of him from the ’70s, he’s posed at the front of a church he visited, wearing a red bow tie and a dark-blue suit, one hand resting on a Bible. He was born in 1925 and lived most of his life in Pennsylvania, graduating from Temple University. During WWII, he served in the Navy. Somewhere along the way, he developed an interest in two topics that he would eventually write dozens of books about: the apocalypse (How the World Will End: Guide to Survival; What in the World Will Happen Next?) and fresh juice (How Juices Restore Health Naturally; Fat Is Not Forever). In that photo of him at the church, he has bushy eyebrows and thick dark hair that’s brushed away from his face. For a man who wrote about sinister conspiracies, he looks surprisingly friendly. Kind of like a guy you might want to grab a juice with.

1. A Little History of the Book of Revelation

My family’s edition combined 666 and 1000 in one volume. These were described on the cover, respectively, as “the thrilling novel of the tribulation period” and “the suspenseful sequel to 666 of the 1,000-year millennium.” If the terms tribulation and millennium mean nothing to you in an apocalyptic context, look no further than your nearest Book of Revelation.

Biblical scholar Elaine Pagels believes Revelation was heavily influenced by its author’s experience during Rome’s war on Jerusalem toward the end of the first century, and that the book’s disturbing images are metaphors for the Roman Empire. Things like a red seven-headed beast wearing a bunch of crowns, a whore drinking blood from a golden cup while riding that beast, giant locusts with human faces, a furious baby-eating dragon with its own sidekick angels, and Jesus emerging from the sky on a white horse to start a war. Christians at the time loved the book. It gave them hope that they would be delivered from persecution from emperors like Nero. And, really, Christians have been projecting current events onto the book ever since.

You might wonder where the hope part comes into play amid the many-headed monsters. It’s when passages describe believers gathered around the throne of God. It’s when the author writes, “God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes …” It’s also when Jesus chains up the dragon and throws Satan into a pit.

When the ‘70s came along, writers like Kirban and Hal Lindsey and televangelists like Jack van Impe merged Revelation with conspiracy theories about world banking systems.

Most people who describe themselves as “born again,” as my family did, believe something like the dramatic interpretation I grew up with, which explains what will happen when the world ends and people are assigned to heaven or hell once and for all.

“Every born-again Christian should be an active, daily witness for his Lord and Savior,” Kirban warns in the introduction to 666. He also suggested that we buy copies and give them to non-Christians who might not read The Bible but who would surely eat up his novel.

One blogger wrote about Kirban’s death in 2010 thusly: “Well he now knows when the Lord will return and I am jealous of his being with Jesus but it is God’s Will!”

2. How the Rapture Works According to a “Well-Qualified Author”

The fundamentalist interpretation of the end of the world goes something like this: At the appointed time (“we know not when,” as preachers would say from the pulpit), people who’ve been properly saved will be whisked away to heaven. Everyone else will stay behind and likely wander around, surprised at all of the empty cars. You’ve probably heard this sort of scene referred to as “the rapture.” In my household, we called it that, too, but we knew being “left behind” was just the start.

Next up: All hell almost breaks loose. The rest will be coming later, but at first there’s just a little taste of it. As the fundamentalist interpretation of Revelation unfolds, God allows Satan to do what he wants to the earth and the earthlings. The seven years of tribulation have begun. Those who see the error of their ways become Christians and suffer hardship for not realizing it in time, and those who still don’t convert pretty much have one foot in hell at this point and get totally taken in by the mark of the beast and the one-world government. Then Jesus comes back and rules in peace for 1,000 years, which is called the millennium. After that, it’s time for the end for real, and people are sorted out one last time.

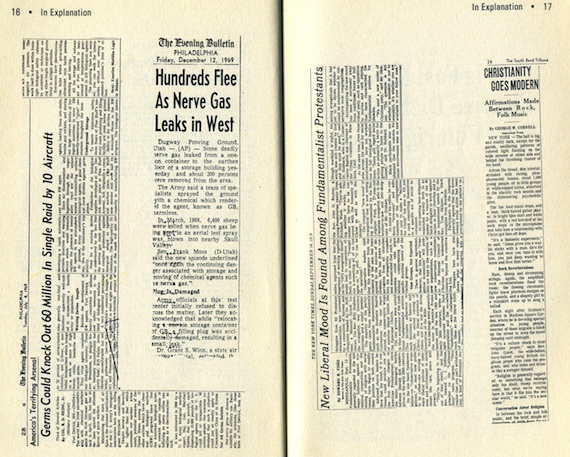

Kirban takes these ideas and goes to town. To set a realistic stage, 666 opens with what appear to be newspaper articles. The rest of the book is full of passages from the Bible, futuristic collages, and photographs with fictionalized captions. For example, a World War II-looking photograph depicting soldiers standing by a wagon of dead bodies is captioned with, “Bodies were carted to disposal centers, ground into special protein cakes.”

Kirban self-published these books and describes himself on the back cover as “a well-qualified author of future events.” He pulls plot points from Revelation, such as a worldwide famine and a showdown in the Middle East, and adds elements of his own devising, such as guillotines and a gadget with “a limp tube of dye” that brands people with the mark of the beast as it “becomes rigid” and releases “a small whisp [sic] of smoke.”

The prose style is, well, peculiar. And forced. As an author, Kirban comes across as a man who would have been just as happy carrying a sign proclaiming that the end is nigh but has figured we might pay more attention if he told us a story instead. The plot is baffling, even as a companion to the inscrutable Book of Revelation itself.

Here’s the book’s main character, reporter George Omega, in the opening scene of the book as he’s flying home after covering a political convention. “As our plane soared into the heavens and the sunlight came breaking through,” George narrates, “I glanced out over the fluffy white clouds below.” Our narrator was thinking of his wife. “One thing I hoped for,” he reveals, “and that was that my wife would leave me alone and quit pestering me to attend church on Sunday.”

The action picks up as the plane takes a sudden lurch. One hundred passengers have disappeared. Omega is one of the passengers left behind, and chills run up and down his spine twice in the first 14 pages alone. (One of the remaining stewardess speaks in all caps: “‘LOOK…,’ she screamed, ‘HALF OF THE PASSENGERS ARE MISSING!’”)

3. Meet the Antichrist. He’s Charming.

Kirban continues mirroring elements of the fundamentalist interpretation of Revelation as he works his way toward the apocalypse. Society crumbles. Evil reigns. But some people are okay with this unseemly state of affairs because they’ve aligned themselves with the devil. The Antichrist is a highly charismatic fellow with a history that includes a head wound. He’s Satan, but he’s in disguise as a caring leader. He’s wily as all get-out, and he quotes The Bible and forms a one-world government so as to more easily bend the will of the world to his own. One currency, one set of laws, lots of protein cakes, no escape.

Kirban’s Antichrist is named Brother Bartholomew. He was “a prominent statesman in the United States” who recently had been elected “honorary leader of the CHURCH OF THE WORLD” (caps not mine). How could such a church exist you ask? Because “the Protestants had finally acquiesced on some silly old notions they had held on to and united with the Catholic church.”

Brother Bartholomew gets put in charge of America after the Rapture, and he starts spinning a narrative on the news that would make your head spin, unless you’ve been watching the news in 2017.

With passages like these, Kirban keyed into an existing conspiratorial undercurrent. Ever since Martin Luther decided the Pope was the whore of Babylon (she’s the one in Revelation riding a beast while drinking blood), Protestants have been suspicious of the Catholic Church. All that pomp, all those crucifixes with Jesus on the cross when we all knew good and well he’d risen from the grave already, all those priests claiming to be our intermediary with God? No thanks!

I grew up hearing that John F. Kennedy, our first Catholic president, might be the Antichrist. I mean, it was just a theory, but I was urged to consider the signs. Charismatic leader, check. Slippery modern morals, check. Social programs that appealed to the masses, check. Alleged interest in God, check. Head wound, check. Lots of questions surrounding his death, check.

Kirban piqued our sensitivities, and not just about Catholicism. During Brother Bartholomew’s rise to power, for example, he creates peace in the Middle East. If this kind of thing sounds fine to you, you are not a time-traveling fundamentalist from the ’70s who attends prophecy conferences on weekends. He pushed all the evangelical buttons, which does more to explain his popularity than his sci-fi plot twists.

Kirban masterfully riled us up with those details. He ALL-CAPPED his way to a mighty vision of just exactly how right we were—about The Bible, and about the dangers facing us. Secularism was making our fellow citizens complacent. Satan was so tricky he would even quote The Bible as he lured us to hell. Denominations espousing liberal interpretations of Scripture were leading their congregations astray. Catholics supporting worldwide alliances didn’t understand that that’s how the Antichrist would come to power. We knew those things to be true, and Kirban shocked us into believing the stakes were even higher.

4. You Got the Real World in My Apocalypse

What really sets Kirban apart as an author was his innovative use of photomontages. The newspaper headlines that open 666 range from “Monkey Brains Kept Alive Outside Skull” to “Christianity Goes Modern.”

One character receives the mark of the beast as she’s forced to kneel at a communion altar for a most unholy act. Soon thereafter, she’s suspended in a glass box to watch while her husband gets his head chopped off by a guillotine that goes “SWOOSH!” with the push of “an electronic release switch.”

Here’s the guillotine outside the church, in case you were wondering.

And don’t worry: I won’t deny you the “bodies were carted away to make protein cakes” one.

At the end of 666, just before 1000, we see an image straight out of Revelation, with some modern artillery added.

The 666-1000 two-books-in-one-volume spectacular concludes with an infographic that features two arrows pointing up for the Rapture alongside descriptions of five of the crowns you may earn on your way up to heaven. In the back of the book, eager readers can order How to Be Sure of Crowns in Heaven by the author, as well as How Juices Restore Health Naturally. Both were available for $4.95 in 1981.

5. My History with the Books

Our living room where we read aloud Kirban’s work nightly was a comfortable place to sit with a book. My father was usually the one reading to us, but my mom took her turn, too. I occasionally offered, but I mostly preferred to sit nearby and listen. I didn’t mind missing whatever was on TV during this time—nothing on TV was this interesting anyway. Also, I liked having inside information about what was going to happen when the world ended.

My parents were careful to clarify that everything described in the book wouldn’t necessarily happen. It was one Bible expert’s exploration of what could happen, based on a lot of things that we knew would happen. We viewed the book as informed speculation. We didn’t know it wouldn’t happen that way, did we? Whether I believed the Antichrist would actually posses a ruby laser ring that harnessed the power of the sun into “a devastating laser beam of destruction” that could wipe out buildings in a poof, I definitely believed the Antichrist would show up and have lots of tricks up his sleeve. And I didn’t want to stick around for it. I wanted to be raptured.

Throughout the ’70s, Kirban traveled the country, talking about his books and investigating new health ideas. In one of his books called Health Guide for Survival, he quotes his friend Bob Conner, who traveled with him and his son—one of Kirban’s five children with his wife, Mary—and helped him sell books after his talks. He and Conner had both received care from a Georgia doctor with unconventional methods that Kirban documented in the book. “I would rather be alive and gullible,” Conner said, “than dead and a skeptic!”

I stopped believing at some point—well into my adulthood, I should admit—but Salem Kirban never did. He was 84 years old when he died, and I assume his gravestone says something like, “May he rest in peace, until he comes back as part of an apocalyptic army.” By the time he died, he’d written 50 books, most of them centered on his two passions: health and the apocalypse. Over the years, Kirban would become more specific in his prophecies, writing a book called I Predict, which claimed that the guillotine would be introduced in America to frighten people and automobiles would be banned. Then it seems he started losing credibility and segued from authorship, to begin selling blue green algae to his fans by mail.

It’s tempting to view Kirban’s two books as straight kitsch, in all their headline-ripping, Bible-quoting, photo-collaging wonder, but as a child I was thrilled to know that people would one day recognize that we had been right all along. It’s more than the weirdness of these books that sticks with me all these years later. Kirban didn’t predict anything like the rise of our current administration, but his books captured the ethos of the post-’60s “born again” movement, and that mindset persists. When more than 80 percent of evangelicals voted for Trump, it seems they looked beyond his obvious flaws and anticipated the policy miracles that were sure to follow. Even Salem Kirban, with his ruby laser ring and his guillotines, knew that what mattered wasn’t so much how the world ended, but how the story made us feel.

During the time my family was reading his books, I remember being excited to know that God had a plan and that I was part of it. I felt sad for everyone who wasn’t going to make it through the apocalypse and into heaven, but mostly glad that I would. We didn’t think this world was our home anyway. We thought this world was going to end in a bang that would prove to everyone who didn’t believe us that we were right.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.