In Mary Gaitskill’s essay, “Leave the Woman Alone!”, one of a bracing, terrific new collection called Somebody with a Little Hammer, Gaitskill takes a look at the media reaction to some recent sex scandals involving politicians. She’s irritated that the wife of the philanderer is presumed to be humiliated; she wonders if those defending the betrayed woman are so enthusiastic because they are secretly gloating; she observes how the mistress gets something of a free pass; and she questions why the cheating men are attacked so viciously, when no one really knows their motives. Gaitskill is particularly perplexed over how, when Elizabeth Edwards continued to support her husband, John Edwards, after his affair was exposed, Edwards herself was berated, perhaps because she refused to let her marriage be defined by others, and instead defined it for herself. Watching these scandals unfold, Gaitskill, ever fascinated with public shamings, asks, “What is going on here?”

It’s a typical Gaitskill set-up. In these brilliant essays, which stretch back to the early 1990s and run up to the last few years, Gaitskill explores emotionally charged situations, catalogues conventional responses to them, then reveals their hidden, psychological underpinnings. Her explorations are incisive and unpredictable — she sticks up for Axl Rose, John Updike, Norman Mailer, Céline Dion, and Linda Lovelace, to name a few of the unexpected; she even sticks up for the philandering politicians mentioned above. The last thing you want to do with any topic is say, “I know just what Mary Gaitskill will think of this.”

In a 2015 article, The New Yorker described Gaitskill by reputation as a “writer not only immune to sentiment but actively engaged in deep, witchy communion with the perverse.” Gaitskill’s oeuvre, from her debut 1988 short story collection, Bad Behavior, through her much-fêted, National Book Award-nominated Veronica, is known for its kinky, heartless, transgressive sexual encounters. She regularly discusses rape. As Gaitskill writes about herself, “In case you don’t know, I’m supposedly sick and dark.” It’s volatile stuff for sure, and Gaitskill’s work is a ready bullet point for anyone ready to politicize sex.

In a 2015 article, The New Yorker described Gaitskill by reputation as a “writer not only immune to sentiment but actively engaged in deep, witchy communion with the perverse.” Gaitskill’s oeuvre, from her debut 1988 short story collection, Bad Behavior, through her much-fêted, National Book Award-nominated Veronica, is known for its kinky, heartless, transgressive sexual encounters. She regularly discusses rape. As Gaitskill writes about herself, “In case you don’t know, I’m supposedly sick and dark.” It’s volatile stuff for sure, and Gaitskill’s work is a ready bullet point for anyone ready to politicize sex.

An example of the heated talk about Gaitskill came in an essay that appeared in The Rumpus in 2013. Author Suzanne Rivecca began her piece: “I hate it when men talk about Mary Gaitskill. I call for a permanent moratorium on men gassily discoursing on Mary Gaitskill.” Rivecca goes on to explain how Gaitskill is grossly misunderstood by men, in particular when it comes to feminism. “When men read Mary Gaitskill, their boners deflate. They feel squeamish and violated and desperate to reimpose a semblance of order and moral authority on their ransacked worlds.” I must say that as a man, my (literary) boner does not at all deflate when reading Gaitskill. But I should be careful here. As Rivecca says, “Even the nice things men say about Gaitskill are annoying.” The Rumpus piece was so strident that Gaitskill herself wrote a public letter to say that, while flattered by the author’s defense of her work, not all men are out to misinterpret her.

For me, the sex in Gaitskill’s work would be prurient if Gaitskill didn’t have such sensitive emotional antennae. I think a lot of the reason Gaitskill writes about sex is for the illusions, lies, power, aggression, and animal instinct it lays bare. For her, it’s a loaded nesting doll of psychological truths.

In my reading, much of what drives Gaitskill is shining a light. She is constantly lasering in on the gap between what is on the surface versus the emotional reality below. She praises the “numinous unconscious” in Charles Dickens, and his “secret life which glimmers in the margins.” She likes artists who “illuminate dark corners,” or who try to “tear things up in order to find what is real.” For Gaitskill, to contemplate darkness is a step toward health. As she writes, “The truth may hurt, but in art, anyway, it also helps, sometimes profoundly.”

In her essay “The Trouble with Following the Rules: On ‘Date Rape,’ ‘Victim Culture’ and Personal Responsibility,” Gaitskill discusses the nomenclature of inner pain, in particular people who inflate it with loaded terms, for example, calling one’s childhood a “Holocaust.”

‘Holocaust’ may be a grossly inappropriate exaggeration. But to speak in exaggerated metaphors about psychic injury is not so much the act of a crybaby as it is a distorted desire to make one’s experience have consequence in the eyes of others, and such desperation comes from a crushing doubt that one’s own experience counts at all or is even real.” (Italics Gaitskill’s).

Here, as elsewhere in Gaitskill, is the recognition of unspoken, deeply damaged interiors. I believe this is one of the reasons Gaitskill inspires such deep allegiance in her readers — those who are wounded know that Gaitskill would see them as they truly are, and would not flinch.

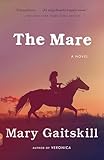

The emotional centerpiece of this collection, “Lost Cat: A Memoir,” is as fine a personal essay as you will find anywhere. It’s ostensibly about Gaitskill’s desperation over a pet cat who goes missing. Gaitskill uses the cat story as an entry point to talk about two other central sources of grief in her life: her relationship with her remote father and her experience taking into her home an inner-city boy named Caesar via The Fresh Air Fund. (This latter relationship became the source material for her recent novel The Mare.) Gaitskill ends up deeply involved with the troubled Caesar, while often failing to help him. At one point she tells Caesar she loves him because, “You are not someone who just wants to hear nice bullshit. You care. You want to know what’s real.” This, by the way, in Gaitskill-world, is as high a compliment as can be paid.

The emotional centerpiece of this collection, “Lost Cat: A Memoir,” is as fine a personal essay as you will find anywhere. It’s ostensibly about Gaitskill’s desperation over a pet cat who goes missing. Gaitskill uses the cat story as an entry point to talk about two other central sources of grief in her life: her relationship with her remote father and her experience taking into her home an inner-city boy named Caesar via The Fresh Air Fund. (This latter relationship became the source material for her recent novel The Mare.) Gaitskill ends up deeply involved with the troubled Caesar, while often failing to help him. At one point she tells Caesar she loves him because, “You are not someone who just wants to hear nice bullshit. You care. You want to know what’s real.” This, by the way, in Gaitskill-world, is as high a compliment as can be paid.

But back to the cat. Gaitskill originally found the cat in Italy, where it was homeless and blind in one eye. She describes the first encounter:

But a third kitten, smaller and bonier than the other two, tottered up to me, mewing weakly, his eyes almost glued shut…His big-nosed head was goblinish on his emaciated potbellied body, his long legs almost grotesque. His asshole seemed disproportionally big on his starved rear.

Gaitskill, needless to say, finds this cat irresistible. She later describes him affectionately as looking like “a little gangster in a zoot suit.” It’s a pattern you see again and again, Gaitskill saying to an outcast, though no one else will say so, you have worth in my eyes.

In an essay about the movie version of Gaitskill’s story “The Secretary,” Gaitskill describes the story’s origin. She had read a magazine article about a girl who was videotaped being spanked by her boss while she stood in a corner and repeated, “I am stupid.” When they were discovered, the boss apologized and paid the secretary $200.

In an essay about the movie version of Gaitskill’s story “The Secretary,” Gaitskill describes the story’s origin. She had read a magazine article about a girl who was videotaped being spanked by her boss while she stood in a corner and repeated, “I am stupid.” When they were discovered, the boss apologized and paid the secretary $200.

On reading it, I laughed, then shook my head in dismay, then thought, What a great story — funny, horrible, poignant, and gross, the misery of it as deep as the eroticism; the misery, in fact, giving the eroticism its most pungent force. The wank-book aspect was clearly indispensable, but what interested me most was, Who is this girl? The Hopeful Innocent in the porn story, the cipher in the news story — what would she be like in real life?

Another piece discusses a favorite old song of Gaitskill’s called “Nowhere Girl.” When Gaitskill first heard it in the early 1980s, the song “lightly touched me with an indefinable feeling that was intense almost because it was so light.” The song was “trying to get your attention, though unconfidently, from somewhere off in a corner. Or from nowhere.” In the book’s title essay, about teaching Anton Chekhov, Gaitskill works in a passage about telling a ragged, obscenity-hurling woman on the street, who might have robbed her, “You are so beautiful.” In all these cases, Gaitskill comes alive when turning toward what others shun.

After “Lost Cat,” the other high point in the collection is Gaitskill’s essay on Linda Lovelace, “Icon.” Lovelace, for those who don’t know, experienced a meteoric ascendancy to fame following her starring role in the 1972 porn flick Deep Throat, about a woman whose clitoris is in her throat, and thus achieves orgasm by giving blow jobs. The essay discusses a smattering of documentaries and biographies about Lovelace, including an incident where she had sex with a dog.

After “Lost Cat,” the other high point in the collection is Gaitskill’s essay on Linda Lovelace, “Icon.” Lovelace, for those who don’t know, experienced a meteoric ascendancy to fame following her starring role in the 1972 porn flick Deep Throat, about a woman whose clitoris is in her throat, and thus achieves orgasm by giving blow jobs. The essay discusses a smattering of documentaries and biographies about Lovelace, including an incident where she had sex with a dog.

The topic has everything Gaitskill gravitates toward: it’s provocative, it’s obscene, it’s about a woman on the fringes of acceptability, who is alternately shamed and lauded. Lovelace is also a psychological puzzle, inconsistent about whether she herself believes she is a victim. Gaitskill is in fact so taken by Lovelace, her terminology turns religious: “A compelling, even profound figure, a lost soul, and a powerful icon.” “It’s impossible to dismiss the appealing, even delightful way [Lovelace] looks in Deep Throat, or her otherworldly radiance in subsequence press conferences.”

In a superb Gaitskillian flourish, she then compares Lovelace’s ordeal to that of Joan of Arc in the famous Carl Dreyer film The Passion of Joan of Arc. Gaitskill admits the comparison is a stretch, but still she writes, “Both women were torn apart by that which they embodied, yet for a moment glowed with enormous symbolic power.”

In a superb Gaitskillian flourish, she then compares Lovelace’s ordeal to that of Joan of Arc in the famous Carl Dreyer film The Passion of Joan of Arc. Gaitskill admits the comparison is a stretch, but still she writes, “Both women were torn apart by that which they embodied, yet for a moment glowed with enormous symbolic power.”

What greater dignity can Gaitskill confer upon Lovelace than to compare her to one of the most famous women to ever live, an icon of religious purity? To dignify something — to say that it is worthy of our respect and attention — is not the same as to redeem it, or forgive it, in the same way that exposing a wound is not the same as treating it. But exposing it is the physician’s first step, and Gaitskill’s. Back in 1990, she told an interviewer for BOMB magazine, “Before you can heal pain, you have to acknowledge it and feel it.”