This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

Confession: I have not marched. Not in any one of the massive protests the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration; not at Kennedy Airport the weekend the executive order banning entry to travelers and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries was announced; nor in the “I Am a Muslim Too” rally, three weeks later. Not in one of the Not My President’s Day rallies. I don’t own a pink pussy hat.

Which is not to say I’m aligned, in any way, with the actions of the current administration. I’ve called my representatives, given to ACLU and Planned Parenthood, and as a member of the media — writing about and advocating for libraries, a progressive and free-thinking American institution — I’m well situated in the enemy-of-the-state camp. I would rather work for the cause than march for it.

Why? For starters, I don’t much like crowds — never mind that I’m a New Yorker who rides the subways. But mainly I think I’m a good 10 years too young to have truly internalized the power of protests. As liberal as they were, my parents believed that children and politics shouldn’t mix, so very little of the ’60s and ’70s spirit of resistance seeped into my consciousness. And the demonstrations I do remember — No Nukes in 1979, 1995’s Million Man March, the endless demonstrations against the Iraq War in 2002 and 2003 — never translated into real change, and thus tamped down in me some basic belief in the ability of collective anger to move the needle. Yes, I know, there’s reverberative power in action that isn’t always immediate or obvious. But I’m sorry, 2017 makes Occupy Wall Street look like a practical joke on idealists everywhere.

I don’t think of myself as jaded. But my outrage has not moved my feet this year. Instead, I think about the protest movements that preceded me: for women’s suffrage, women’s reproductive rights, labor laws, civil rights. What was it about them that had the power to change policy, to change the world?

2.

2.

March 25 will mark the 106th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, where 146 garment workers — most of them recent Jewish and Italian immigrants aged 16 to 23, some as young as 14 — were killed in a fire that swept through the eighth, ninth, and 10th floors of a Greenwich Village factory. Most of the labor and safety laws we think of as humane and sensible didn’t exist: the exit and stairwell doors were locked to keep workers from stealing or taking unauthorized bathroom breaks, there were no sprinklers, and the single fire escape collapsed mid-fire, killing 20 workers. New York fire truck ladders only reached the sixth floor. Sixty-two of the dead jumped or fell from the windows.

Although union rallies and labor law protests had been in full swing since the 19th century, the horror of the Triangle fire fueled a new level of outrage in the fight for unions and better working conditions, as well as building-safety laws and women’s suffrage. (The company’s owners, who both survived the fire by escaping to the roof, were indicted on charges of first- and second-degree manslaughter but eventually acquitted; they were, however, found liable of wrongful death during a 1913 civil suit.)

Little was written on the fire until Leon Stein’s 1962 account The Triangle Fire; then came a handful of young adult and children’s books in the 1970s. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 21st century — in the aftermath of yet another New York tragedy that galvanized the nation — that the Triangle fire took its place in the literary consciousness. Alice Hoffman, Stephen King, and Robert Pinsky have used the fire as an element in novels, short stories, and poems, and Katharine Weber’s novel Triangle weaves the story of the fire’s last living survivor with the 2001 World Trade Center attacks.

Little was written on the fire until Leon Stein’s 1962 account The Triangle Fire; then came a handful of young adult and children’s books in the 1970s. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 21st century — in the aftermath of yet another New York tragedy that galvanized the nation — that the Triangle fire took its place in the literary consciousness. Alice Hoffman, Stephen King, and Robert Pinsky have used the fire as an element in novels, short stories, and poems, and Katharine Weber’s novel Triangle weaves the story of the fire’s last living survivor with the 2001 World Trade Center attacks.

3.

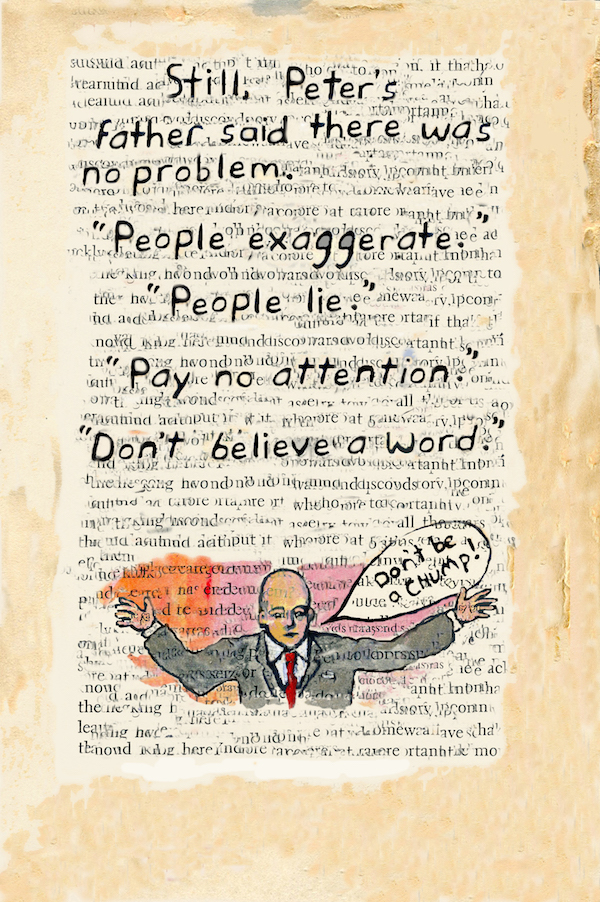

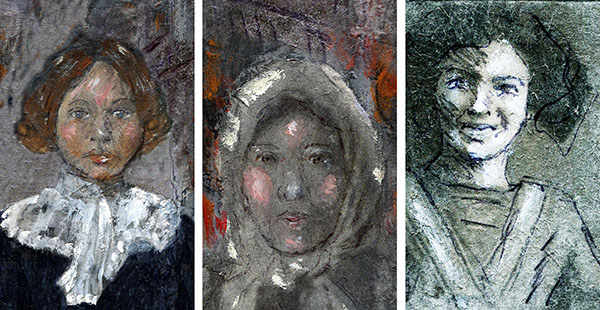

Now Delia Bell Robinson, a Vermont-based artist, has written and illustrated A Shirtwaist Story (Fomite Press), the story of a slightly more unexpected reverberation. She tells of her friendship with “Peter,” the grandson of one of the factory’s owners, and the family legacy of silence and guilt sprung from the disaster. Robinson also addresses the fire itself, but obliquely, with somber-toned, haunting paintings of immigrants and workers interspersed with colorful illustrations of Peter’s life that would not be out of place in a storybook.

In fact, Robinson says, the initial paintings about Peter were done directly on the pages of a children’s book she found in a library discard pile. She began writing his story when the two first met in the 1990s, in Montpelier, Vt., and she was drawn to his tales of growing up a “poor little rich boy” on New York’s Upper East Side — undergoing surgery as a baby while his parents vacationed in Cape Cod, riding his bike in Central Park, touring Europe with his family. “It was like living in a clever play,” writes Robinson, “lots of smart repartee and some mild clawing for social ascendancy.”

In 2001 Robinson walked into her local café and found Peter there, looking bereft. As she tells it:

“What’s wrong with you?” I asked.

“The last survivor of the shirtwaist fire just died.”

“Yes, I heard that on the radio,” I said, “It is sad, but why does that make you so much sadder than everyone else?”

“Because my grandfather owned the factory.”

Suddenly all my little cartoons were reduced to trivia.

The story of the final survivor’s death had been in the news and was already on Robinson’s mind. His admission left her with no doubt that she wanted to tell not only Peter’s story, but that of the fire as well. She began reading up on the event; what emerged was a book’s worth of sumptuous, haunting paintings.

The story of the final survivor’s death had been in the news and was already on Robinson’s mind. His admission left her with no doubt that she wanted to tell not only Peter’s story, but that of the fire as well. She began reading up on the event; what emerged was a book’s worth of sumptuous, haunting paintings.

“Hours of historical research had resulted in pages and pages of information, yet I didn’t want this to be a book filled with warmed-over facts,” Robinson says. “If I stripped the information down, it read like bad haiku. So how to present it all? I needed a new way to retell an already much-discussed history. Ultimately, I discarded my collected information, replacing facts with paintings.”

Robinson’s paintings of the people, cityscapes, and factory scenes, many of them black-and-white, are dark and affecting. The artist’s hand is present throughout, in her use of layering and collage — paint and graphite over type, postcards, photo emulsion transfers, and newsprint, with her own paper-clipped notes making appearances. While illustrators usually work larger than the eventual reproduction size in order to tighten the artwork and hide flaws, Robinson purposely reversed the equation, working on three-by-four-inch to eight-by-11-inch paper

“I wanted pen scratches, hesitation lines, brush marks, dirt, and paper fibers to intensify the atmosphere in each drawing. I therefore made small paintings on much rubbed and scrubbed paper,” she explains. “When done, they were enlarged and cropped to my satisfaction so every twist and turn of the pen or brush became heightened, bringing the character of each work forward.”

The result is a series of complex images appropriate to a complex story; in the closing sequence of portraits, the victims gaze out from the pages steadily, neither accusing nor letting us off the hook.

“Who was responsible?” writes Robinson. “The New York City Buildings Department passed the blame to the State Labor Commission, the fire inspectors, the fire department, the fire marshals, the owners, and finally to no one.”

4.

“Our mother believed that children should grow like weeds,” says Robinson of her wildly creative — and only sporadically supervised — childhood. “She disapproved of interference or anything shaping creative impulses. In addition she was an Adele Davis food faddist, so delicious food was off the menu. Our beds were as hard as rocks and we were not allowed pillows. This regime would result in true individuality; young Titans with straight backs, healthy bodies, and unique opinions.”

Although she has painted, drawn, and sculpted all her life (in addition to a nursing career “to live and pay for paint”), Robinson kept her writing, other than essays for Ceramics Monthly, to herself. Her fiction, as she describes it, was not “polished or literary,” but the characters “were present as invisible friends for me during long Vermont winters and years of child rearing.” A Shirtwaist Story, published when Robinson was 71, is her debut book.

She had not originally intended to make Peter’s story public — “Relaying a true story with painful elements and balancing it against a desire to cause no harm is tricky.” — and although he had no problem with her drawing his childhood story for her own purposes, she understood his need for privacy. When a publisher expressed interest in the manuscript she approached Peter, who “turned away and changed the subject.”

But when his mother died a few years later, he guardedly told Robinson that he had changed his mind, and that the whole story should be told.

Robinson worked with Fomite Press’s husband-and-wife team of Marc Estrin and Donna Bister to refine A Shirtwaist Story, which she described as originally “a Siamese twin of a book, one topic but two bodies of dissimilar work.” They encouraged her to blend the two time frames, keeping the original tone and texture of each, and approved of her wishes to include the painted-over text of the original library book. Keeping “all the blots, scribbles, and fragments of letters I’d heaped on [the pages]” made for extra work, she added, but Bister and Estrin never complained.

5.

Indeed, the fire has affected many more lives than the 146 lost, or the factory owners, or any of their survivors. Anyone who has escaped an apartment building via the fire stairs, or who stood up and took a union-mandated break during their workday, owes at least a part of that legislation to the Triangle fire.

Indeed, the fire has affected many more lives than the 146 lost, or the factory owners, or any of their survivors. Anyone who has escaped an apartment building via the fire stairs, or who stood up and took a union-mandated break during their workday, owes at least a part of that legislation to the Triangle fire.

But what is it about that fire, or the women who turned out for suffrage two years later, or the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the Selma to Montgomery marches two years after that, that mustered the strength of enough individuals to ultimately change the world? And what is it about an event like the Triangle fire — so small in the context of today’s numbers — that still keeps its memory so close to the surface of our national anger? Was the world simply a smaller place then?

In a way, yes. “Before the fire, it was generally accepted that ‘the business of America is business.’ Politicians, government — they were all about helping business prosper,” posits Triangle author Weber (a Bloomer herself, having published her first novel at 39). “The horror of the fire…was maybe the first time there was a feeling that government should ‘do something’ to protect the worker. Laws had not been broken, you know — the building codes, the safety codes — nothing at all was a violation — because nothing was necessary to protect the worker, only profits.”

The fire also dovetailed with the beginnings of the women’s movement — 123 of the victims were women or girls — and the immigrant narrative was taking on an important life of its own in the national story. “I think everyone was galvanized by the sense of the tragic broken promise that had been made to those immigrants who had accepted the Emma Lazarus welcome and were living their American dream,” said Weber. The fire “woke” people — including Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945 and the first woman ever appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. She witnessed the fire and saw the workers jumping, Weber noted, and became a lifelong advocate for labor and women’s rights. Perkins was a wealthy woman who was galvanized to make the concerns of the poor her own, loudly and vociferously — a role filled these days primarily on the back end, by foundations and celebrities, who can let their money do the marching. But where is the one percent who will roll up their sleeves and do the work at hand?

Perhaps it is only fitting that the fire should be on our minds, then, as the new administration’s infringements on the rights of immigrants, workers, women, and the poor manifest themselves daily. Marching is good, but so is work — the process of dredging up what is strong and raw in our collective outrage: writing editorials, lobbying elected officials, calling out untruths where we find them, making a sound where we can be heard. Solidarity is good and valuable, but it is only one step in the process. And that process is something I have not lost faith in — nor, fortunately, have the many artists working everywhere to make sure that we don’t forget why we are, and should be, angry.

For more on Delia Bell Robinson, check out this Q&A over at Bloom.

All illustrations © Delia Bell Robinson