I came of age as a writer under the tutelage of the Internet. As a result, I believed — for a while, at least — that to write successful creative nonfiction, I had to have harrowing personal stories. First-person writing is the Internet’s voice, and narratives that shock are the Internet’s currency. With a surprising or scandalous personal story, writers get “shares,” build digital platforms, and find book deals. As Laura Bennett wrote for Slate last year, “For writers looking to break in, offering up grim, personal dispatches may be the surest ways to get your pitches read.” Bennett offers examples of successful pieces, the titles of which range from “I Was Cheating on My Boyfriend When He Died” to “My Gynecologist Found a Ball of Cat Hair in My Vagina.”

When I started finding my footing as a writer, I believed that I had a chance for publication largely because I had a story to tell which was — well — harrowing. At the age of 21, I had flown to Southeast Asia to teach English in a university as a covert missionary in a small town surrounded by rice fields. Less than a year later, several of my students and closest friends were interrogated by the police because of their affiliation with me; my teaching contract was cancelled and my visa was revoked. Rumors swirled around the university that I’d been an undercover CIA agent. Add to this a romantic subplot (I met my future husband there) and I had a tale to tell of love, heartbreak, and adventure.

But once I’d finished that book, I wondered if I had anything worthwhile left to say. Would I have to wait for another extreme experience before I could write again?

But once I’d finished that book, I wondered if I had anything worthwhile left to say. Would I have to wait for another extreme experience before I could write again?

I observed the careers of other writers who had moved from blog to book. Some began to depend on oversharing intimate details to retain a strong connection with their audience. Some, stuck in the “brand” they’d created, told the same story over and over again. Swiftly I realized that I would have to work to avoid getting caught in the solipsism of the modern memoirist, turning only and quickly to my life’s experiences for source material. Writing beyond the “I” would require a jump toward craft, a willingness to wait for long-form thoughts to coalesce, and a careful attention to the world outside myself. In fact, it would be work that was harrowing in another sense of the word, which originally referred to preparing fields for planting by breaking up the soil. A true harrowing essay would dig deeper, ultimately performing a generative function.

To find material in the mundanities of everyday life requires a “reeducation,” Philip Gerard says in “Taking Yourself Out of the Story: Narrative Stance and the Upright Pronoun,” so that writers become attentive to

just those moments in the day, in their loves and friendships, in their family dynamics, in their historical moments, in their interactions with the natural world, that remain genuinely perplexing, vexing, luminous, unresolved. In short, they must be nudged to recognize that life remains a mystery — even one’s so-called boring life.

For me, one of the surest ways to celebrate the world as luminous and full of mystery is by cultivating a constant curiosity, an incurable interest — a kind of attention that is the same as — or that leads to — research. Research is a habit, “an attitude of open-minded alertness,” writes Gerard, that “frees you for a time from paralyzing self-absorption.” Attention leads to exploration. This is precisely the habit I needed to develop in order to mature as a writer.

But is it possible to integrate research into the personal essay in a way that allows the research to take primacy? This was what I wondered, in my quest to avoid getting caught up in my own stories or my “personal brand.” I have told my story, you can find it in my book. Now I want to tell some other stories. I want to look at the world around me with attentiveness, to write slowly, to build up patience as I build up folders of research before jumping to an argument, a conclusion, a moral to the story. How do I write a personal essay without too much “I”? How do I make readers care about a fact? How do I make nonfiction truly creative? How do I give a narrative drive to facts about garden plants or dramatic tension to a historical story that was resolved 200 years ago? Perhaps most of all, how do I come to understand my own life better through understanding the world around me, and how do I share that kind of insight with readers?

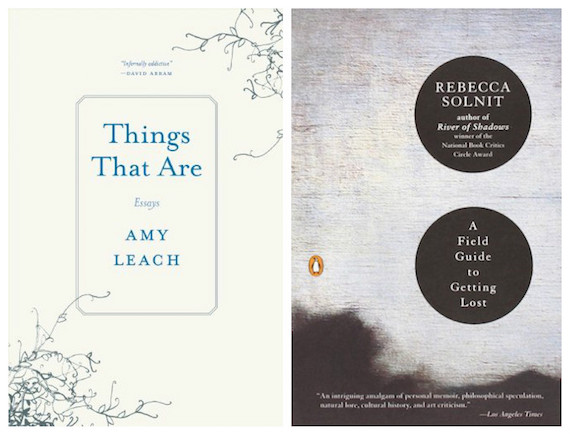

I have found some helpful directions in the work of creative nonfiction writers like Amy Leach and Rebecca Solnit. These writers combine memoir/personal essay with history, natural sciences, art criticism, and philosophical meditations, but they successfully make the leap from “nonfiction” to “creative nonfiction.”

One way they accomplish this is by being present in the essay through tone. Solnit’s tone is authoritative, serious, and philosophical. In “The Blue of Distance,” an 18-page essay in A Field Guide to Getting Lost (2006), the first person pronoun does not appear until the 15th page. This works in part because previous essays in the collection have introduced readers to Solnit — her religious heritage, family photographs, travels, and classes taught. Readers already understand the stakes of lostness and exploration in Solnit’s personal life. But even apart from that, Solnit is able to make the essay personal rather than simply historical by her use of tone, which is interpretive as well as informational. For the first 15 pages, Solnit tells stories from American history about explorers and settlers who got lost, were transformed, and then returned in some capacity to their homes. She wins readers’ trust by weaving meticulously researched stories together with quotes from original accounts, and is careful to note when her interpretation of the events is entering the narrative, using signaling words like “perhaps.”

Amy Leach has an even more distinctive personal tone, filled with delight and attentive to the poetic within the factual as she studies things of earth (fainting goats, existential pandas, sensitive sea cucumbers) and things of heaven (supernova imposters, constellations, God) in her collection Things That Are (2014). Rather than routing the natural world through her own experience, Leach seeks to explain and reorder it. Leach inserts herself into the narrative rarely, but the joy she finds in her subjects is self-revelatory: we know something about the author simply by the way she loves her subjects. When she does show up in the narrative, she is invitational (“Come and miss the boat with me.”) and droll (“wooly bears have one of the least advanced defense mechanisms among insects, although theirs is the reaction with which I most strongly identify: when distressed, the wooly bear rolls up into a ball.”). One wants to keep reading just to remain present to the joy she finds in the world.

Another way these writers turn nonfiction into creative nonfiction is by use of innovative and beautiful language. Rather than saying “Young pea plants form two leaves every four and a half days,” Leach says:

The young pea plant lives by diligent routine, forming two tiny equal leaves every four and a half days. If leaf-leaf on a Tuesday morning, then leaf-leaf on a Saturday evening, and leaf-leaf on Thursday morning. Someone who helps peas — a friar or a bee — may look in on them, but young peas are as autonomous as mushrooms and as responsible as clocks…

By the use of innovative language (like “leaf-leaf”), imaginative scenarios (the friar or the bee checking in on the pea), and unexpected metaphors (peas autonomous as mushrooms), Leach adds emotional resonance to scientific fact, putting the pea’s existence on a level with human existence, filled with drama and diligence, humor and passion.

Solnit, too, can make facts sing. Rather than saying “Coho salmon travel upstream in winter,” Solnit says “I had seen them, too, golden female and ruby male thrashing their way up shallow water in the early dusk of drizzly midwinter.” Details make facts visible, and evocative words like golden and ruby (as opposed to yellow and red) add regal tones to the scene.

But regardless of how beautifully written accounts of history or inquiries into natural science are, I find that as a reader I am looking for a turn in creative nonfiction: a point in an essay where the writer nods toward a more transcendent meaning, a metaphorical resonance that allows history or science or bald fact of any kind to speak directly to my life. Many authors do this right away, using fact as an illustration in the first paragraph or two, and then turning to direct the majority of their attention to a larger thesis. But Solnit points to metaphorical resonances and larger points only in oblique ways, expecting her reader to connect the dots for herself. In her essay “Two Arrowheads,” for instance, she moves from a story of a relationship that has ended to an in-depth discussion of the film Vertigo to the biological makeup of hermit crabs to analysis of Oedipus Rex without directly connecting the subjects. It was only upon rereading that I began to understand how each subject connected to the larger themes of sight and home.

But regardless of how beautifully written accounts of history or inquiries into natural science are, I find that as a reader I am looking for a turn in creative nonfiction: a point in an essay where the writer nods toward a more transcendent meaning, a metaphorical resonance that allows history or science or bald fact of any kind to speak directly to my life. Many authors do this right away, using fact as an illustration in the first paragraph or two, and then turning to direct the majority of their attention to a larger thesis. But Solnit points to metaphorical resonances and larger points only in oblique ways, expecting her reader to connect the dots for herself. In her essay “Two Arrowheads,” for instance, she moves from a story of a relationship that has ended to an in-depth discussion of the film Vertigo to the biological makeup of hermit crabs to analysis of Oedipus Rex without directly connecting the subjects. It was only upon rereading that I began to understand how each subject connected to the larger themes of sight and home.

Leach makes such rhetorical turns — pointing from her subject to a transcendent or metaphorical meaning — late in her essays. In “In Which the River Makes Off with Three Stationary Characters,” for example, Leach spends four pages describing beavers, three pages on salmon and their parallels with beavers, and then only in the last two pages does she turn to humans, how our experience being moved by unseen forces is similar to that of the beaver and the salmon. When asked about this, about whether anyone has asked her to use a more “traditional” structure, Leach replied that she wanted “for the beavers to be beavers, for salmon to mean salmon, rather than being proof of a point.” If we aren’t truly paying attention to the world, we are in danger of using it for our own purposes or intellectual agendas. “This is how I often think,” she says, “– in a thesis-driven way — but it’s not how I want to think, and I love how in writing you can work out the way you want to think.” When she did get there, at the end of that essay, I scribbled a note to myself in awe: “what a pay-off.”

When I see the world more clearly, I see myself more clearly too, and in new ways. Writers like Leach and Solnit help me believe that the harrowing essay will not rule the day, and that writing that pays careful attention to the world and to language, tone, and metaphorical resonance can be equally powerful as and far more enduring than the personal essay with the most online shares. To love the world, to pay attention to it, to practice patience, to cultivate the habit of curiosity that is research — these can be key to developing a writerly voice that will last and that will matter.