I am in the habit of slipping objects between the pages of whatever book I am reading: sometimes to mark a place, more often because a book is the safest place I know for letters or receipts or tickets or whatever I need to bring with me somewhere.

I have carried books for over two decades of adult life now, years spent largely in Illinois and New York, but also on vacations and trips that go much farther afield. Earlier this month, I went through every book in our Manhattan apartment to see what I could discover. This meant flipping pages in roughly 700 books, mostly novels, but also poetry books, memoirs, and essays, searching for pieces of my own history.

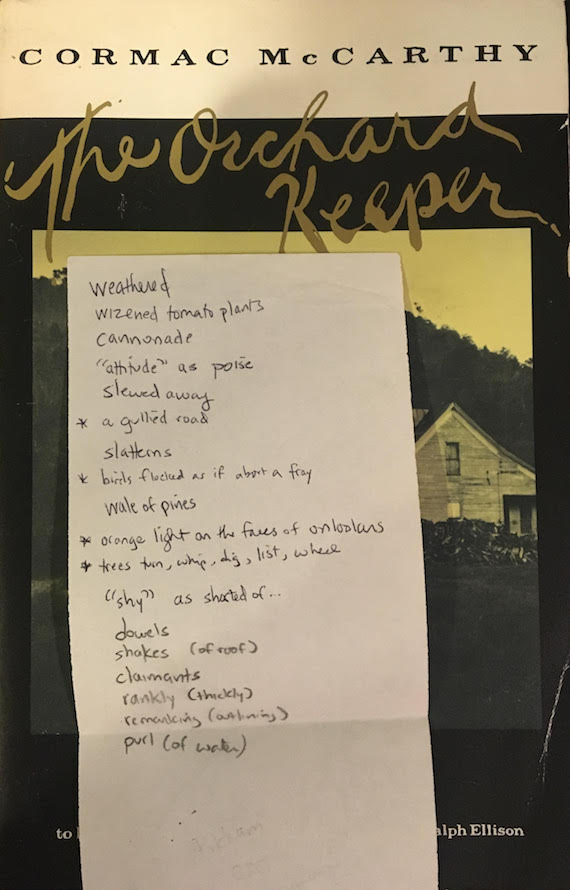

The Orchard Keeper by Cormac McCarthy

A slim copy request slip from Columbia’s writing program, circa 1999. I was workshopping my first novel and adjusting to life in New York City. McCarthy’s rustic prose was like a postcard from the woodsy plain in Michigan where I grew up. On the flip side of the slip, a handwritten list of obscure words in the text I admired — slewed, purl, wale, rictus — words that, alas, I then tried to jam into my own doomed manuscript.

The Blue Estuaries by Louise Bogan

The Blue Estuaries by Louise Bogan

Torn strips of paper mark dozens of poems that I liked as an undergraduate at Northwestern, back when I wanted to be a penniless poet when I grew up. I remember announcing this career path to my parents one chilly bright autumn afternoon while we milled outside Ryan Field before a football game. They took the news remarkably well. Today, I remember nothing of what drew the 20-year-old me to poems like “The Frightened Man” or “Betrothed.”

John Adams by David McCullough

A full sheet (minus one) of Forever Stamps from the U.S. Post Office. The picture on the stamps: the Liberty Bell, of course

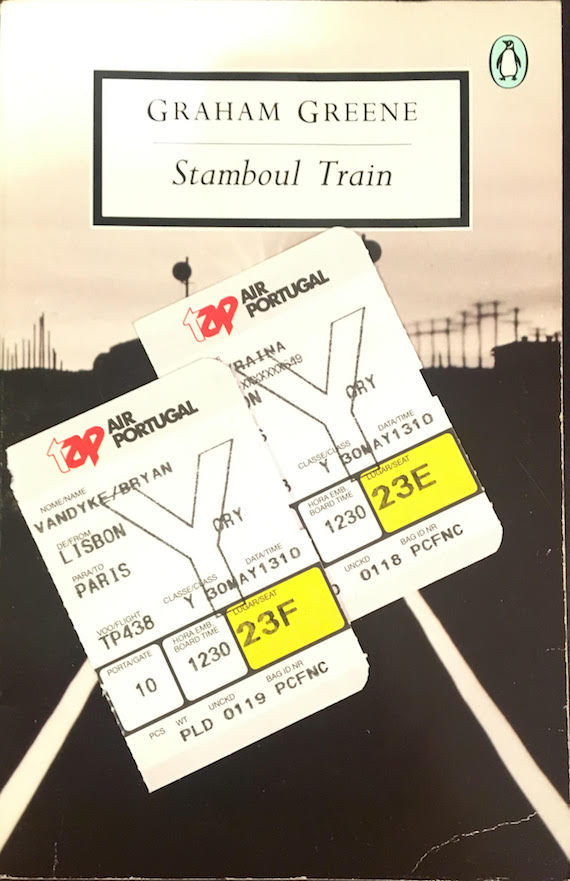

Stamboul Train by Graham Greene:

Two colorful ticket stubs, mementoes from an official starting point of my own: Flight 438 from Lisbon to Paris on May 30, 2004, Seats 23E and 23F, one for me and one for my wife, Raina, on the flight back home from our honeymoon.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The business card of a Vice President of Strategy for Razorfish, a major Internet consultancy in the ‘00s — and perhaps the strangest bedfellow possible for a book about Stalinist oppression. But these were my late-20s, a time of routine contradictions, when I fancied myself a professional Web geek by day but a self-serious failed novelist at the night.

Christine Falls by John Banville (writing as Benjamin Black)

The inspection certificate for our brand new Toyota RAV-4 from May 6, 2009. Despite having sworn never to have a car in the city again, Raina and I leased the Toyota because our daughter was two and we wanted to improve our ability to flee for the suburbs and the helpful hands of her parents whenever our nascent parenting skills failed us.

A Multitude of Sins by Richard Ford

A Multitude of Sins by Richard Ford

A small card reminding me that I have a haircut on Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2006 at 6 p.m. on Waverly Street. A decade later I still get my hair cut at the same place, though I now prefer Thursdays.

Devil’s Dream by Madison Smartt Bell

The floor plan for the apartment that Raina and I moved into in 2011, right before our son — our second child — was born. Our new neighborhood’s streets were littered with more trash than our previous, and car alarms would trumpet the start of the work day for livery drivers at 6 a.m., but the apartment felt big enough for all four of us, plus our dog, and in New York City having enough space means having everything.

So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell

A yellow Post-It note that says “Waverly and Mercer” and “penne and chocolato,” written in my hand. I know I met many friends near the intersection of these two Village streets over the years — before we’d get pints of Belhaven at Swift or maybe cheap margaritas at Caliente Cab Company — but the meaning has gone just as those friends have left for Westport, Conn., or Chicago, Ill., or wherever friends go.

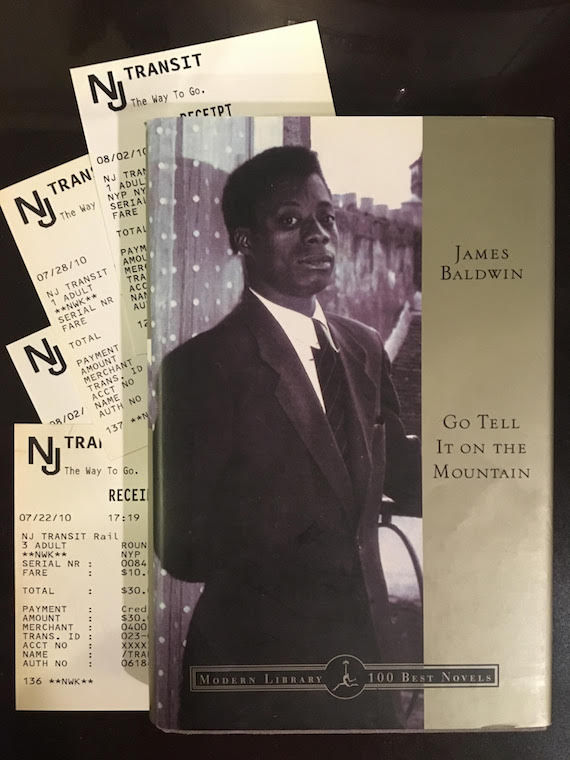

Love Always by Anne Beattie; Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin; Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre; and many more.

For 10 years, from 2003 through 2013, I commuted from New York to New Jersey each day — an hour each way. I used to tell people that I didn’t mind, because I had so much time to read books. And it’s true, I did a lot of reading then. But I did mind. I slipped three off-peak round trip passes for New Jersey Transit trains in the Beattie; 4 more receipts and three canceled tickets in the Baldwin; and, in the Sartre, six receipts, more than six round trips, perhaps a signal of how hard I worked to find joy in that joyless fusion of philosophy and fiction.

The Stranger by Albert Camus

A greeting card and a blank envelope. The card has a cartoon king on the cover and inside it says, “You rule!” There is nothing else written anywhere.

City of Glass by Paul Auster; A Rage to Live by John O’Hara; God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and A Man Without a Country by Kurt Vonnegut; This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff; The 9/11 Commission Report; Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom by August Wilson; Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima; and on and on.

City of Glass by Paul Auster; A Rage to Live by John O’Hara; God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and A Man Without a Country by Kurt Vonnegut; This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff; The 9/11 Commission Report; Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom by August Wilson; Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima; and on and on.

During that long commuting decade, I often took not just the New Jersey Transit train but also a local tram in Newark. To ride the Downtown line, I had to buy a lavender ticket from a machine at the top of a long escalator. On the platforms at select stops, conductors would surprise commuters and demand proof that we each had used the ticket punch clocks to validate our 50-cent passes. I find these lavender alibis slipped in the pages of dozens and dozens of books.

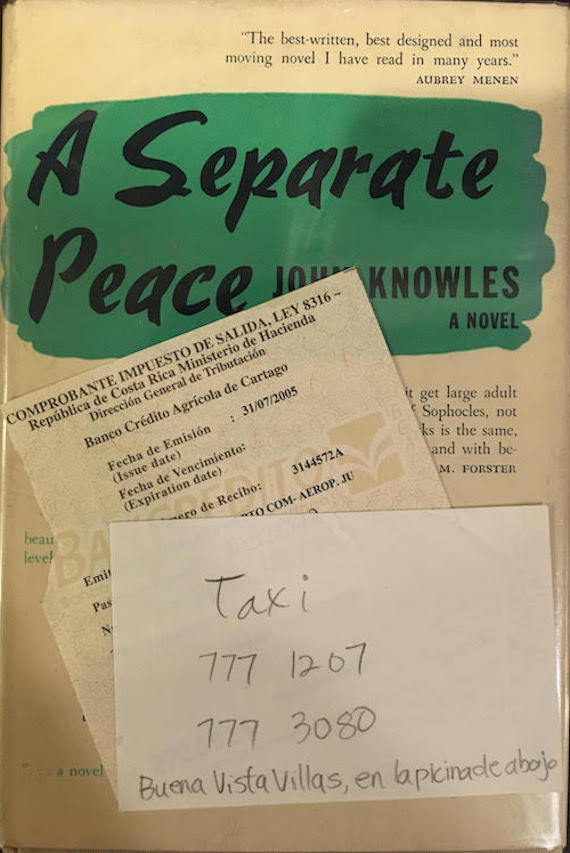

A Separate Peace by John Knowles

Inside this hardcover I find the phone number for a taxi company and words written in Spanish: Buena Vista Villas en la picinade abajo. Also, a receipt for a $26 car ride. I know that Raina and I were in Costa Rica for my brother’s wedding in 2005. But I don’t speak or write Spanish. And I don’t know where the taxi brought us.

The Master of Petersburg by J.M. Coetzee

The Master of Petersburg by J.M. Coetzee

A full-color 3×2 photo strip. Two duplicates of a portrait still from my daughter’s kindergarten year, her tiny face smiling out, forever five years old. I brought this book with me when I went to a writer’s retreat for a week in 2013. I tried but failed to engage in the Coetzee, never finished it. Spent a lot of time looking at the little girl.

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

A piece of notebook paper from 1999 with phrases from the text that I liked (“the smell of lavender,” “like a person who is listening to a sea-shell held to her ear”), and a toll-free telephone number. I dial the telephone digits now, curious, but a recording says the number is no longer in service.

The Triumph of Achilles by Louise Glück

There is, technically, nothing in this book. But it is hardly empty. I can still find the poem marked with a hard diagonal line at the page corner, as if the paper were folded over a knife. “Sooner or later you’ll begin to dream of me,” the poem promises. “I don’t envy you those dreams.” A haunting line called out by an ex-girlfriend who borrowed the book after we broke up. Two decades later, the curse has yet to come true.

There is, technically, nothing in this book. But it is hardly empty. I can still find the poem marked with a hard diagonal line at the page corner, as if the paper were folded over a knife. “Sooner or later you’ll begin to dream of me,” the poem promises. “I don’t envy you those dreams.” A haunting line called out by an ex-girlfriend who borrowed the book after we broke up. Two decades later, the curse has yet to come true.

Atonement by Ian McEwan

Atonement by Ian McEwan

A tiny, white, blank, one-inch-by-a-half-inch Post-It note.

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

A Polaroid taken last year when it was my son’s turn to be in kindergarten: We are seated together in his classroom on a morning I don’t precisely remember — just as, I suppose, the father in The Buried Giant cannot quite recall his own son — although anyone can see this moment still matters by the bright and radiant looks on our faces. And will always matter, I like to think. Even if that’s not possible to prove.

After I finished this long walk through the books of the last 20 years, I asked myself whether I should leave the found objects or take them out. Should I strip the books clean for whoever comes through next — perhaps for my children when they are adults, if their taste in books resemble mine at all? Or shall I leave the objects more or less where I found them, a story-within-the-stories that tells the tale of one reader’s life for anyone who cares to sleuth out the details? This wasn’t a hard decision, as you’d guess. The objects go back. The page turns.

Image credit: Pexels/Suzy Hazelwood.