Charles Dickens didn’t exactly have a dirty pen. This, after all, was the man who promised his delicate Victorian readers that he would “banish from the lips” of all his characters “any expression that could by possibility offend.”

Not the easiest of promises to make because, let’s face it, the Victorians were easily offended.

Case in point: These were the people who cringed over the word “trousers,” because men’s pants were worn a little too close to a certain tabooed male appendage for comfort. But, by and large, Dickens kept his promise like a classy gent, never using outright profanity in any of his 15 novels. But Dickens was obsessed with capturing reality in all of his writings. It just took a bit of cleverness to pull it off, to politely wiggle his way out of that very tight corset of Victorian censorship, and here are a few examples of how he did it:

1. Gormed

[Mr. Peggotty] swore a dreadful oath that he would be “Gormed” if…[his generosity] was ever mentioned again. — David Copperfield

It’s the most famous and talked-about curse word in Dickens’s oeuvre. In the Dickensian universe, this is as profane as profanity gets — despite the fact that no one in that universe seems to know what this “dreadful oath” actually signifies. The long-standing theory, popularized by the OED, is that Dickens invented the word “gormed” as an even milder substitute for “gosh-darned.” Yes, they do share the same first and last letter, but Dickens played his delicate game with profanity even safer than that. Rather than inventing the word (and thus having to later defend it), Dickens built “gormed” on an actual, though obscure, English word. The verb “to gorm” once meant to “to stare blankly, vacantly” at something, likely related to the Irish gom, “a stupid-looking person.” Dickens’s “gormed” thus could be safely translated as something more like “confounded, stupefied” — hardly a swear word at all — and bearing no trace of any attack on the Almighty.

It’s the most famous and talked-about curse word in Dickens’s oeuvre. In the Dickensian universe, this is as profane as profanity gets — despite the fact that no one in that universe seems to know what this “dreadful oath” actually signifies. The long-standing theory, popularized by the OED, is that Dickens invented the word “gormed” as an even milder substitute for “gosh-darned.” Yes, they do share the same first and last letter, but Dickens played his delicate game with profanity even safer than that. Rather than inventing the word (and thus having to later defend it), Dickens built “gormed” on an actual, though obscure, English word. The verb “to gorm” once meant to “to stare blankly, vacantly” at something, likely related to the Irish gom, “a stupid-looking person.” Dickens’s “gormed” thus could be safely translated as something more like “confounded, stupefied” — hardly a swear word at all — and bearing no trace of any attack on the Almighty.

2. What the Deuce!

If the Victorians were squeamish about taking God’s name in vain, they had an equal dread of mentioning the devil’s. Sort of an awkward prohibition for them, as swearing by the devil tripped way too easily off most Victorian tongues. Their one acceptable remedy — euphemisms.

Almost every questionable word, circa 19th century, had its polite substitute (one of the acceptable euphemisms for “trousers” was, in fact, “inexpressibles”). And most convenient of all, the devil had his own choice euphemism — namely the word “deuce” — nonchalantly inserted into popular period phrases such as “What the deuce!” and “The deuce and all!” — expressions that Dickens used freely and frequently in his writing. There’s a lot of speculation on how “deuce” acquired its devilish reputation and, moreover, why it was acceptable to Victorian sensibilities. Simple answer, no one really knows.

3. I’ll be De’ed

If Dickens had a favorite indecent oath, it would have been the oh-so-versatile D-word. That’s, more or less, exactly how Dickens referred to it in his writing, as “D” something or other. That might seem cute and childish to us today, but even by dropping three letters of a four-letter word, Dickens was dangerously skirting the fringes of Victorian decency. Everyone knew what he meant and he probably lost a few of his more prudish fans over momentary lapses of censorship like these:

If Dickens had a favorite indecent oath, it would have been the oh-so-versatile D-word. That’s, more or less, exactly how Dickens referred to it in his writing, as “D” something or other. That might seem cute and childish to us today, but even by dropping three letters of a four-letter word, Dickens was dangerously skirting the fringes of Victorian decency. Everyone knew what he meant and he probably lost a few of his more prudish fans over momentary lapses of censorship like these:

He flung out in his violent way, and said, with a D, “Then do as you like.”

— Great Expectations“Capital D her!” burst out Caroline…“I’ll give her a touch of the temper that I keep!”

— “Mrs. Lirriper’s Lodgings”He says…that he’ll be de’ed if he doesn’t think he looks younger than he did ten years ago.

— “The Old Couple”

4. Oh, Merdle!

Dickens’s character names are among the most brilliant and quirky creations in English literature.

Fantastically conceptualized names such as Scrooge, Pecksniff, and Bumble read and sound like perfect incarnations of who and what these characters are at their core. And sometimes it isn’t pretty. Nowhere more so than with the ignominious Dickensian duo with a swear word hidden in both their names — Mr. Merdle from Little Dorrit and Mr. Murdstone from David Copperfield.

Fantastically conceptualized names such as Scrooge, Pecksniff, and Bumble read and sound like perfect incarnations of who and what these characters are at their core. And sometimes it isn’t pretty. Nowhere more so than with the ignominious Dickensian duo with a swear word hidden in both their names — Mr. Merdle from Little Dorrit and Mr. Murdstone from David Copperfield.

Didn’t catch the dirty pun? Perhaps it will help by explaining that Dickens was a Francophile for most of his life, reveling in all things French, especially the language, which he gushingly described as “Celestial.” But even celestial tongues have their crudities and Dickens would have known one of its most popular: merde, literally “excrement,” the French equivalent of our s-word. And boy did that word came in handy for Dickens! Nothing sums up Mr. Merdle’s character better than saying that he is, well, full of merde. He’s one of literature’s biggest financial fakes, erecting the Victorian equivalent of a massive Ponzi scheme that ends up ruining countless investors. The same goes for Mr. Murdstone, though his poop-fullness is of a different sort. Namely, Murdstone is convinced that “all children” are “a swarm of little vipers” needing to be relentlessly beaten into submission.

5. Bleepin’ Grammar

Avid readers of Dickens often get the feeling that Boz routinely got bored with having to perform this prim circumlocution with profanity. It’s obvious that sometimes he simply didn’t want to invent a curse word, swap in a euphemism, or use a clever pun, sometimes he just wanted to let his seedier characters say exactly what they mean — to let that loose old language rip. And actually, on occasion, he did exactly that by doing what TV producers do today. He bleeped out bad words (but kept in the bleeps, of course, so we wouldn’t be robbed of all the fun). Dickens’s “bleeps” are actually quite funny indeed, relying on innocuous grammatical terminology to delicately remind his readership that not everybody spoke with such polite decorum, that some Victorian characters’ “parts of speech are of an awful sort.” Here comically recorded in Dickens’s article on crime, “On Duty with Inspector Field:”

I won’t, says Bark, have no adjective police and adjective strangers in my adjective premises! I won’t, by adjective and substantive! Give me my trousers, and I’ll send the whole adjective police to adjective and substantive!

Notice Dickens’s rare slip-up with the use of “trousers.” A double indecency!

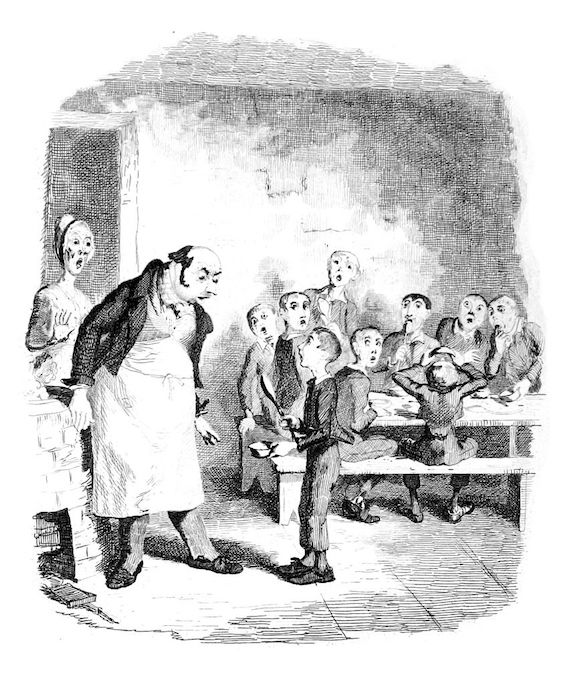

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.