1.

It is an innocent train ride, full of the banal chatter we save for our post-work hours, until my coworker Marthine pulls out her phone and shows me a video of her laughing son. At what she calls the “sweet spot,” those tender months between squalling and teething, Arun (whose name refers to the dawn in Sanskrit) glimpses himself in the mirror and chortles, drool pooling between his lips and chin. He is as smitten with himself as the world is with him. He observes himself; he loves what he sees. We observe him; we love what we see.

There is a portion at the end of Belle Boggs’s The Art of Waiting in which, as she’s holding her infant at home, a mason says, “Imagine if there was only one baby in the whole world…Wherever that baby was, we’d put down our things and go see it.” “You’re right,” she says. “I’d go.” At 26, newly struck with baby fever, I would be there in line, craning my neck to behold.

I can’t point to the moment that it started, and yet it accrues every day, the inverse of my bank account. The way I accuse men of thinking with their penises, I’ve begun thinking with my ovaries — sidelined by tiny outfits, ogling at babies on Instagram, indulging vague daydreams about pregnancy clothes worn with wide-brimmed straw hats. I am an unfit mother: a smoker, a shopper, a too-frequent cheese eater, and bill forgetter. I inhabit (with my husband) a tiny one-bedroom in the most expensive city in the country, where we can barely afford our square footage. I’ve over-drafted my bank account buying cat food. I’ve celebrated the arrival of my period in college with cake and champagne, bought anxiety-inducing pregnancy tests at the pharmacy with nail polish and cheap beer. And yet; and yet.

2.

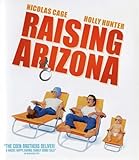

“It’s spring when I realize I may never have children,” Boggs opens the first chapter, this forthrightness setting a precedent for the rest of the memoir. The Art of Waiting delves directly into the process of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in all its pre- and mis-conceptions, its prose like a sledgehammer cracking through drywall. She probes beyond the clinical terminology and atmosphere of the doctor’s office and takes as her subjects cicadas and gorillas, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, and Raising Arizona. She sees motherhood everywhere, like I do: it’s inescapable, especially because we do not have it.

“It’s spring when I realize I may never have children,” Boggs opens the first chapter, this forthrightness setting a precedent for the rest of the memoir. The Art of Waiting delves directly into the process of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in all its pre- and mis-conceptions, its prose like a sledgehammer cracking through drywall. She probes beyond the clinical terminology and atmosphere of the doctor’s office and takes as her subjects cicadas and gorillas, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, and Raising Arizona. She sees motherhood everywhere, like I do: it’s inescapable, especially because we do not have it.

In a book that could easily become insular, instead the reader finds Boggs’s considered, holistic approach, wherein she covers families of numerous formations and facets — different races, socioeconomic categories, and world views pepper this intelligent and insightful treatise on fertility, medicine, and motherhood, which spans years of Boggs’s life and years of research on childbearing, its successes, and its failures. Science meets narrative; the global meets the personal; the reader meets the author, or at least feels that way, a knowing closeness that builds with every revelation and dispersal of personal, painful fact. The world of reproduction is hardly beautiful, with its sanitized wands, needles, and oocytes, and yet we’re privy to it, as if standing next to the stirrups.

We’re privy, too, to stories that vary dramatically from Boggs’s. There are her mentors, professors, and friends who choose to forgo children in favor of careers and lives of artistry. There is Virginia Woolf, who writes, feeling euphoric after completing The Waves, “Children are nothing to this.” There are gay couples facing rampant discrimination. There are her friends who adopt from overseas, and face the harrowing knowledge that their black child will live an entirely different life in their mountain community because of the color of his skin, the story of his origins.

We’re privy, too, to stories that vary dramatically from Boggs’s. There are her mentors, professors, and friends who choose to forgo children in favor of careers and lives of artistry. There is Virginia Woolf, who writes, feeling euphoric after completing The Waves, “Children are nothing to this.” There are gay couples facing rampant discrimination. There are her friends who adopt from overseas, and face the harrowing knowledge that their black child will live an entirely different life in their mountain community because of the color of his skin, the story of his origins.

Perhaps the most important lesson that The Art of Waiting imparted was its insistence on the long game; that the things worth wanting are worth waiting for, and that impatience is a tax we pay for arriving at our fateful conclusions. There’s a decided sense of fatedness about the entire book, a necessary corollary for a treatise on building a family. Who are we meant to be, and in relation to whom? Is a struggle with infertility a sign that we’re meant to walk a different path? Is resisting the body’s futility an act of bullheadedness, foolhardy? Boggs, who describes herself as non-religious, persists, questioning every phase of intrauterine insemination (IUI), the consideration of adoption, and eventually of in-vitro fertilization (IVF). The result is ultimately a baby — Beatrice — but the question lingers, essential to the book: if we’re always in the process of becoming, what are we meant to become? What if that end isn’t the one we had in mind?

Boggs aptly describes the arduousness of ART without writing an arduous narrative — she spares no detail, be it negotiating insurance coverage with a cut-rate pharmacy or injecting herself with one of many medicines each cycle. These details never become drudgery. They’re an inherent and interesting part of the narrative of modern pregnancy. It’s easy to forget, amidst the deftness of Boggs’s prose, that this book depicts a clinical process.

The experience of child-rearing, of adoption, of infertility, impacts more than just the person at their center, despite the feelings of isolation they bring about. Mr. Cheek, the aforementioned mason, embodies this knowledge. “He knew something bigger, more profound,” Boggs writes. “Each baby is born not just to her parents, but to the world surrounding her. To neighbors, friends, teachers, enclosure mates. To ex-cons and allomothers and cousins and grandmothers, who will each want a peek and will each have some impact.” The same could be said of unintended childlessness; in the void created by such powerful wanting, whole communities are implicated.

I pass babies in their carriages on my street and sometimes we lock eyes, as if my desire is transparent. Round-headed and wide-eyed, taking in the new world, they take me in, and I take them in right back, pining for something I’m too sacrilegious or jaded to call a miracle. Meanwhile, I care for my cats. I love my husband. I yearn, and I scheme, and I imagine what fate will deal me next year, or the year after that. In the present, I am only a collection of wants, imagining what it’s like to shape the destiny of a tiny, malleable being.

“Keep trying. Be content. How do you reconcile those two messages?” Boggs writes in her epilogue. She has no exact answers; this is not a textbook. Rather, it’s a primer on waiting and wanting, something we’re arguably always doing, whether it’s for the end of the workday or whatever missing piece we feel might complete us, for whatever unknowable reasons. We’re waiting for the world to adapt, to accept all forms of family; for our bumbling bodies to perform as we wish; for fate to unfurl like a carpet, its threads and fibers as intricately, tightly woven as our own desires.