I took Purity in one long gallop, reading it over four days at my friend’s house. Sarah had already read it, and was desperate for me to hurry up and finish so we could talk about it. The minute I put it down, I went to go find her. She was wearing clean white shorts and a miraculously uncreased blue linen shirt. I was wearing a regretted purchase from H&M — a white cotton dress with little roses on it that looked fine in the shop, but depressing on me. I told Sarah that I’d finished and she said, “Have you noticed,” she asked, “the clothes thing?”

Yes, the clothes thing. The whole point of Jonathan Franzen is the richness of his description, his eye for a telling detail. Where are all the clothes, then? Why are there almost no descriptions of what anyone is wearing? It seems like the most amazing oversight. How is it possible that two characters can have an extremely detailed conversation about a third character being “jealous of the internet”, or that we are subjected to a long and over-vivid description of Pip’s boring job, or the smells of different kinds of soil, and yet we are given almost nothing in the way of clothing? They all might as well be walking around naked. The only detailed description of an outfit in the first section, for instance, is the following: “she saw Stephen sitting on the front steps, wearing his little-boy clothes, his secondhand Keds and secondhand seersucker shirt.” The word “seersucker” is latched onto and used twice more (“she whispered into the seersucker of his shirt”; “she said, nuzzling the seersucker”). It gets slightly better as the novel progresses, but not by much. The first time Pip sees Andreas Wolf, for instance, his “glow of charged fame particles” are vividly described, but his clothes? No. Even Tom’s mother’s significant sundress is described only as being “of Western cut.” It’s unsettling.

I know this to be a petty criticism, but there are all kinds of nerds who write long, aggrieved blog posts about how some novelist got a car wrong, or misdated the death of an actress. Clothes have always been important to me, and while their fictional depiction might be beneath some people’s notice, it is always one of the first things I see. Clothes aren’t just something one puts on a character to stop her from being naked. Done right, clothes are everything — a way of describing class, affluence, taste, self-presentation, mental health, body image. Clothes matter. Besides all that, clothes are fun. Descriptions of dresses got me through War and Peace. I think about Dolores Haze’s outfits on a near-daily basis (“check weaves, bright cottons, frills, puffed-out short sleeves, snug-fitting bodices and generously full skirts!”) I think about her cotton pyjamas in the popular butcher-boy style. Holden Caulfield’s hounds-tooth jacket, and Franny Glass’s coat, the lapel of which is kissed by Lane as a perfectly desirable extension of herself. Sara Crewe’s black velvet dress in A Little Princess, and the matching one made for her favourite doll. The green dress in Atonement (“dark green bias-cut backless evening gown with a halter neck.”) Anna Karenina’s entire wardrobe, obviously, but also Nicola Six’s clothes in London Fields. Nicola Six’s clothes are fantastic.

I know this to be a petty criticism, but there are all kinds of nerds who write long, aggrieved blog posts about how some novelist got a car wrong, or misdated the death of an actress. Clothes have always been important to me, and while their fictional depiction might be beneath some people’s notice, it is always one of the first things I see. Clothes aren’t just something one puts on a character to stop her from being naked. Done right, clothes are everything — a way of describing class, affluence, taste, self-presentation, mental health, body image. Clothes matter. Besides all that, clothes are fun. Descriptions of dresses got me through War and Peace. I think about Dolores Haze’s outfits on a near-daily basis (“check weaves, bright cottons, frills, puffed-out short sleeves, snug-fitting bodices and generously full skirts!”) I think about her cotton pyjamas in the popular butcher-boy style. Holden Caulfield’s hounds-tooth jacket, and Franny Glass’s coat, the lapel of which is kissed by Lane as a perfectly desirable extension of herself. Sara Crewe’s black velvet dress in A Little Princess, and the matching one made for her favourite doll. The green dress in Atonement (“dark green bias-cut backless evening gown with a halter neck.”) Anna Karenina’s entire wardrobe, obviously, but also Nicola Six’s clothes in London Fields. Nicola Six’s clothes are fantastic.

Aviva Rossner’s angora sweaters and “socks with little pom-poms at the heels” in The Virgins. Pnin’s “sloppy socks of scarlet wool with lilac lozenges”, his “conservative black Oxfords [which] had cost him about as much as all the rest of his clothing (flamboyant goon tie included).” May Welland at the August meeting of the Newport Archery Club, in her white dress with the pale green ribbon. I quite often get dressed with Maria Wyeth from Play It As It Lays in mind (“cotton skirt, a jersey, sandals she could kick off when she wanted the touch of the accelerator”). I think about unfortunate clothes, as well. I think about Zora’s terrible party dress in On Beauty, and about how badly she wanted it to be right. The meanest thing Kingsley Amis ever did to a woman was to put Margaret Peele in that green paisley dress and “quasi-velvet” shoes in Lucky Jim. Vanity Fair’s Jos Sedley in his buckskins and Hessian boots, his “several immense neckcloths” and “apple green coat with steel buttons almost as large as crown pieces.”

Aviva Rossner’s angora sweaters and “socks with little pom-poms at the heels” in The Virgins. Pnin’s “sloppy socks of scarlet wool with lilac lozenges”, his “conservative black Oxfords [which] had cost him about as much as all the rest of his clothing (flamboyant goon tie included).” May Welland at the August meeting of the Newport Archery Club, in her white dress with the pale green ribbon. I quite often get dressed with Maria Wyeth from Play It As It Lays in mind (“cotton skirt, a jersey, sandals she could kick off when she wanted the touch of the accelerator”). I think about unfortunate clothes, as well. I think about Zora’s terrible party dress in On Beauty, and about how badly she wanted it to be right. The meanest thing Kingsley Amis ever did to a woman was to put Margaret Peele in that green paisley dress and “quasi-velvet” shoes in Lucky Jim. Vanity Fair’s Jos Sedley in his buckskins and Hessian boots, his “several immense neckcloths” and “apple green coat with steel buttons almost as large as crown pieces.”

This list changes all the time, but my current favorite fictional clothes are the ones in A Good Man is Hard to Find. There is no one quite like Flannery O’Connor for creeping out the reader via dress. Bailey’s “yellow sport shirt with bright blue parrots designed on it” contrasts in the most sinister way with the The Misfit’s too tight blue jeans, the fact that he “didn’t have on any shirt or undershirt.” I’d also like to make a plug for one of The Misfit’s companions, “a fat boy in black trousers and a red sweat shirt with a silver stallion embossed on the front of it.” Any Flannery O’Connor story will contain something similar, because she used clothes as exposition, as dialogue, as mood. Anyone to who clothes matter will have their own highlight reel, and will argue strenuously for the inclusion of Topaz’s dresses in I Capture the Castle, or Gatsby’s shirts, or Dorothea Brooke’s ugly crepe dress. They will point out, for instance, that I have neglected to mention Donna Tartt, top five fluent speaker of the language of dress. What of Judge Holden’s kid boots, in Blood Meridian? What about Ayn Rand, who, as Mallory Ortberg has noted, is just about unparalleled?

This list changes all the time, but my current favorite fictional clothes are the ones in A Good Man is Hard to Find. There is no one quite like Flannery O’Connor for creeping out the reader via dress. Bailey’s “yellow sport shirt with bright blue parrots designed on it” contrasts in the most sinister way with the The Misfit’s too tight blue jeans, the fact that he “didn’t have on any shirt or undershirt.” I’d also like to make a plug for one of The Misfit’s companions, “a fat boy in black trousers and a red sweat shirt with a silver stallion embossed on the front of it.” Any Flannery O’Connor story will contain something similar, because she used clothes as exposition, as dialogue, as mood. Anyone to who clothes matter will have their own highlight reel, and will argue strenuously for the inclusion of Topaz’s dresses in I Capture the Castle, or Gatsby’s shirts, or Dorothea Brooke’s ugly crepe dress. They will point out, for instance, that I have neglected to mention Donna Tartt, top five fluent speaker of the language of dress. What of Judge Holden’s kid boots, in Blood Meridian? What about Ayn Rand, who, as Mallory Ortberg has noted, is just about unparalleled?

The point is, we do not lack for excellent and illuminating descriptions of clothes in literature. Given such riches, it is perhaps churlish to object to the times when people get it wrong. Haven’t we been given enough? Apparently not. Just as I can think of hundreds of times when a writer knocked it out of the park, attire-wise, (Phlox’s stupid clothes in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, all those layers and scarves and hideous cuffs), I can just as easily recall the failures. There are a variety of ways for an author to get clothes wrong, but I will stick to just two categories of offense here.

The point is, we do not lack for excellent and illuminating descriptions of clothes in literature. Given such riches, it is perhaps churlish to object to the times when people get it wrong. Haven’t we been given enough? Apparently not. Just as I can think of hundreds of times when a writer knocked it out of the park, attire-wise, (Phlox’s stupid clothes in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, all those layers and scarves and hideous cuffs), I can just as easily recall the failures. There are a variety of ways for an author to get clothes wrong, but I will stick to just two categories of offense here.

1. Outfits that don’t sound real

Purity again, and Andreas’s “good narrow jeans and a close-fitting polo shirt.” This is wrong. Andreas is a charismatic weirdo, a maniac, and I struggle to believe that he would be slinking around in such tight, nerdy clothes. Another jarring example is Princess Margaret’s dress, in Edward St. Aubyn’s Some Hope: “the ambassador raised his fork with such an extravagant gesture of appreciation that he flicked glistening brown globules over the front of the Princess’s blue tulle dress.” The Princess here is supposed to be in her sixties. Would a post-menopausal aristocrat really be wearing a blue tulle dress? Is the whole thing made out of tulle? Wouldn’t that make it more the kind of thing a small girl at a ballet recital would choose? St. Aubyn’s novels are largely autobiographical, and he has mentioned in interviews that he met the allegedly blue-tulle-dress-wearing Princess on a number of occasions. Maybe that really is what she was wearing. It doesn’t sound right, though, or not to me.

Purity again, and Andreas’s “good narrow jeans and a close-fitting polo shirt.” This is wrong. Andreas is a charismatic weirdo, a maniac, and I struggle to believe that he would be slinking around in such tight, nerdy clothes. Another jarring example is Princess Margaret’s dress, in Edward St. Aubyn’s Some Hope: “the ambassador raised his fork with such an extravagant gesture of appreciation that he flicked glistening brown globules over the front of the Princess’s blue tulle dress.” The Princess here is supposed to be in her sixties. Would a post-menopausal aristocrat really be wearing a blue tulle dress? Is the whole thing made out of tulle? Wouldn’t that make it more the kind of thing a small girl at a ballet recital would choose? St. Aubyn’s novels are largely autobiographical, and he has mentioned in interviews that he met the allegedly blue-tulle-dress-wearing Princess on a number of occasions. Maybe that really is what she was wearing. It doesn’t sound right, though, or not to me.

One last example, from The Rings of Saturn: “One of them, a bridal gown made of hundreds of scraps of silk embroidered with silken thread, or rather woven over cobweb-fashion, which hung on a headless tailor’s dummy, was a work of art so colourful and of such intricacy and perfection that it seemed almost to have come to life, and at the time I could no more believe my eyes than now I can trust my memory.” One believes the narrator, when he says that he cannot trust his memory, because this actually doesn’t sound like a dress, or not a very nice one. It sounds like a dress a person might buy from a stall at a psytrance party. The word “colourful” here is a dead giveaway that the narrator does not necessarily have a particular dress in mind: what kind of colours, exactly? “Intricate” is also no good — it seeks to give the impression of specificity, but is in fact very vague.

One last example, from The Rings of Saturn: “One of them, a bridal gown made of hundreds of scraps of silk embroidered with silken thread, or rather woven over cobweb-fashion, which hung on a headless tailor’s dummy, was a work of art so colourful and of such intricacy and perfection that it seemed almost to have come to life, and at the time I could no more believe my eyes than now I can trust my memory.” One believes the narrator, when he says that he cannot trust his memory, because this actually doesn’t sound like a dress, or not a very nice one. It sounds like a dress a person might buy from a stall at a psytrance party. The word “colourful” here is a dead giveaway that the narrator does not necessarily have a particular dress in mind: what kind of colours, exactly? “Intricate” is also no good — it seeks to give the impression of specificity, but is in fact very vague.

2. Outfits that make too much of a point

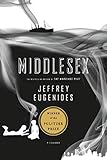

Many people are suspicious of fashion. They do not trust it or like it, and, while they see that it serves a purpose, they wish it was somehow enforceable to make everyone wear a uniform at all times. Deep down, they also believe that anyone who does take pleasure in it is lying to themselves, or doing it for the wrong reasons. I argue with such people in my head all the time, because this is not what clothes are about for me, at all. I argue with the books they have written as well. To be fair to Jeffrey Eugenides, he is mostly excellent on the subject of dress. The Lisbon girls’ prom dresses and the Obscure Object’s High Wasp style are in my own personal highlight reel. The Marriage Plot is different, though. It is deeply cynical on the subject of dress. Clothes in that novel are always an affectation or a disguise, a way for a character to control the way others see her.

Many people are suspicious of fashion. They do not trust it or like it, and, while they see that it serves a purpose, they wish it was somehow enforceable to make everyone wear a uniform at all times. Deep down, they also believe that anyone who does take pleasure in it is lying to themselves, or doing it for the wrong reasons. I argue with such people in my head all the time, because this is not what clothes are about for me, at all. I argue with the books they have written as well. To be fair to Jeffrey Eugenides, he is mostly excellent on the subject of dress. The Lisbon girls’ prom dresses and the Obscure Object’s High Wasp style are in my own personal highlight reel. The Marriage Plot is different, though. It is deeply cynical on the subject of dress. Clothes in that novel are always an affectation or a disguise, a way for a character to control the way others see her.

Here is Madeline, getting Leonard back “Madeleine … put on her first spring dress: an apple-green baby-doll dress with a bib collar and a high hem.” Here is Madeline, trying to seem like the kind of girl who is at home in a semiotics class: “She took out her diamond studs, leaving her ears bare. She stood in front of the mirror wondering if her Annie Hall glasses might possibly project a New Wave look…She unearthed a pair of Beatle boots … She put up her collar, and wore more black.” And here is Madeline, failed Bohemian, despondent semiotician, after she has gone back to reading novels: “The next Thursday, “Madeleine came to class wearing a Norwegian sweater with a snowflake design.” After college, she realizes that she can dress the way she has always, in her haute-bourgeois heart, wanted to dress: like a Kennedy girlfriend on holiday. Another costume, for a girl who doesn’t know who she really is. The problem with these clothes is not that they don’t sound real, or that they are badly described. It’s that Madeline only ever wears clothes to make a point, to manipulate or to persuade her audience that she is someone other than she really is. Worse, there is the implication that she has no real identity outside from what she projects. It’s exact opposite approach to O’Connor’s wardrobe choices in A Good Man is Hard to Find. The guy in the red sweat shirt, with the silver stallion? He is not wearing those clothes for anyone but himself. Same with The Misfit and his frightening jeans.

Here is Madeline, getting Leonard back “Madeleine … put on her first spring dress: an apple-green baby-doll dress with a bib collar and a high hem.” Here is Madeline, trying to seem like the kind of girl who is at home in a semiotics class: “She took out her diamond studs, leaving her ears bare. She stood in front of the mirror wondering if her Annie Hall glasses might possibly project a New Wave look…She unearthed a pair of Beatle boots … She put up her collar, and wore more black.” And here is Madeline, failed Bohemian, despondent semiotician, after she has gone back to reading novels: “The next Thursday, “Madeleine came to class wearing a Norwegian sweater with a snowflake design.” After college, she realizes that she can dress the way she has always, in her haute-bourgeois heart, wanted to dress: like a Kennedy girlfriend on holiday. Another costume, for a girl who doesn’t know who she really is. The problem with these clothes is not that they don’t sound real, or that they are badly described. It’s that Madeline only ever wears clothes to make a point, to manipulate or to persuade her audience that she is someone other than she really is. Worse, there is the implication that she has no real identity outside from what she projects. It’s exact opposite approach to O’Connor’s wardrobe choices in A Good Man is Hard to Find. The guy in the red sweat shirt, with the silver stallion? He is not wearing those clothes for anyone but himself. Same with The Misfit and his frightening jeans.

Those who are suspicious of fashion tend to believe that people (especially women) only ever wear clothes as a form of armor, a costume, and never because they get pleasure out of it. Madeline, in other words, doesn’t wear clothes because she likes them, but because she likes what they do. I find this line of thinking very depressing.

There are other categories (clothes that I think sound ugly, clothes in over-researched historical novels where the writer takes too much relish in describing jerkins and the smell of wet leather etc.), but these two stand out. I’m not asking for anything too excessive — just a few more details, a bit more effort when getting a character dressed. Clothes matter, to some of us, and we need to see them done right.

Image: John Singer Sargent, Wikipedia