Richard Vine has a day job, a very good one. He’s managing editor of Art in America magazine, where he has written hundreds of articles about Chinese ink art, the Chicago Imagists, photographers from Mali, Korean sculptures installed in the gardens at Versailles, and the way art subsidies work in Singapore. Now Vine has a new entry on his globe-spanning resume: noir novelist.

Vine’s debut novel, SoHo Sins, has just been published by the Hard Case Crime series, and it’s a terrific addition to the pulp tradition, which Charles Ardai, a co-founder of Hard Case, summed up this way: “There’s a body on page one. The cover art is classical realism with a heightened sense of sexuality and menace. The stories are heart-stopping, a wonderful blend of high and low culture.”

SoHo Sins checks all the boxes. The moody cover art is by Robert Maguire, a prolific illustrator who produced more than 600 pulp covers beginning in the mid-20th century. It shows a man in a fedora and trench coat in a darkened alley, looming over a seated blonde in a red dress, a fallen woman in obvious distress. There’s a dead body in the opening sentence: “I slept rather badly the first few nights after Amanda’s murder.” And the story that unspools from there, as narrated by the suavely decadent SoHo art dealer and real estate speculator Jackson Wyeth, is a wonderful blend of high art and low-down deeds, a whodunit with room for de Kooning paintings and child pornography, art biennials and back-room deals, millionaires and mistresses and murder. The novel spins around a question: did the mentally unstable art collector and tech millionaire Philip Oliver murder his socialite wife in their SoHo loft, as he claims, even though he was apparently in Los Angeles when the killer pulled the trigger?

The novel is set during the late 1980s or early1990s, when big money like Philip Oliver’s had begun to infect and distort the New York art scene. The money has gotten even more obscene in the ensuing quarter-century, partly because dealers like Jackson Wyeth have never been inclined to ask indelicate questions. “You can’t deal successfully in art if you dwell on where the money comes from and how it gets made,” the glib Wyeth says at one point. “I concern myself with my clients’ tastes and credit ratings, not their ethics.” The novel’s money-drunk art scene is described on the cover, in suitably breathless prose, as “a world of adultery and madness, of beautiful girls growing up too fast and men making fortunes and losing their minds. But even the worst the art world can imagine will seem tame when the final shattering secret is revealed…”

The worst the art world can imagine — those words are the key. Simply put, SoHo Sins succeeds because it was written by a man with a day job, a job that gives him intimate knowledge of how a subculture works – its personalities and preoccupations, its business practices, its styles, its silliness and occasional beauty and, above all, the ugly money that pumps through its rotten heart. You have to be inside such a world to plausibly imagine the worst it can imagine.

In America today it’s maddeningly difficult to make a living writing books, and it’s just about impossible to make a living writing fiction. That’s largely because the pool of writers is constantly growing while the pool of serious readers, especially readers of fiction, is constantly shrinking — never a good business model. As a result, all but a few writers of fiction have some sort of day job, which most of them view as a time-sucking, soul-crushing impediment to the making of their art.

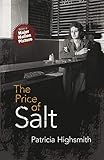

But as Richard Vine has shown, a day job can be a counter-intuitive blessing to the writer of fiction. Since most people spend nearly half of their waking hours at work, the workplace would seem like natural and fertile ground for setting a novel. We already have more than enough novels, written in flawless, bloodless MFA prose, about a bunch of Oberlin grads struggling to find themselves in brownstone Brooklyn. As Jason Arthur pointed out on this site recently, we need more novels that draw on worlds where people do actual work — like the art dealers and pornographers and tycoons and cops in SoHo Sins, or the metal scrappers in Matt Bell’s Scrapper, the eco-saboteurs in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, the wheat-threshers in Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the drug dealers in Richard Price’s Clockers, the admen in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, John le Carré’s spies, Elmore Leonard’s hard-working petty criminals, and the lonely department store clerks in Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt. These can be worlds the author knows first-hand, or they can be vividly imagined worlds of the past, such as the 17th-century Dutch commodity speculators in Davis Liss’s The Coffee Trader, or the Irish immigrant sandhogs who dug the New York City subway tunnels in Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness.

But as Richard Vine has shown, a day job can be a counter-intuitive blessing to the writer of fiction. Since most people spend nearly half of their waking hours at work, the workplace would seem like natural and fertile ground for setting a novel. We already have more than enough novels, written in flawless, bloodless MFA prose, about a bunch of Oberlin grads struggling to find themselves in brownstone Brooklyn. As Jason Arthur pointed out on this site recently, we need more novels that draw on worlds where people do actual work — like the art dealers and pornographers and tycoons and cops in SoHo Sins, or the metal scrappers in Matt Bell’s Scrapper, the eco-saboteurs in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, the wheat-threshers in Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the drug dealers in Richard Price’s Clockers, the admen in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, John le Carré’s spies, Elmore Leonard’s hard-working petty criminals, and the lonely department store clerks in Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt. These can be worlds the author knows first-hand, or they can be vividly imagined worlds of the past, such as the 17th-century Dutch commodity speculators in Davis Liss’s The Coffee Trader, or the Irish immigrant sandhogs who dug the New York City subway tunnels in Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness.

The point is that a day job — as a commodities trader, say, or a construction worker or an art dealer — can be a way for a writer to admit readers to plausible, fully realized worlds that would otherwise be off-limits. Richard Vine grasps this. In a recent interview in Brooklyn Rail, Vine discussed how his day job informed his novel:

SoHo Sins, you might say, is a lament not for the art world that was, or is, but the art world that is rapidly emerging. By now, its corruption by unregulated wealth is almost complete; this book simply imaginatively extends present trends…My projection goes into the immediate past rather than the immediate future, but that reversal of vectors is just an amusing bit of game-play to help highlight the present.

An argument could be made that the art world today, ultimately dependent as it is on the buying decisions of a few super-rich individuals, is fatally tainted throughout. (Artnet.com reports a new financial scam almost every week.) Do some further digging, and the facts soon reveal that no one can become that rich, or maintain that level of inherited wealth, without being a moral criminal. Such disproportionate lucre is accumulated either through activities that are literally illegal or through the utterly unconscionable exploitation of employees, stockholders, taxpayers, and customers — an economic crime and a moral one.

A world that’s “fatally tainted throughout” — and populated with operators like Philip Oliver, who uses his tech company to both finance his art acquisitions and distribute child pornography around the world. Could there be a richer backdrop for a noir novel? And could there be a better person to write it than someone who has a day job on the inside, deep in the tainted shadows, where the dirty money does its work?