It is late in the fourth Act of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, and the romantically devastated yet resilient Nina Zarechnaya draws a parallel between her life and that of a seagull that has been shot and killed near her family’s country home. The play hinges on this moment, which dispassionately asserts how grand aspirations cannot be dismissed, even if they are brought low by human recklessness, superficiality, and indifference:

Men are born to different destinies. Some dully drag a weary, useless life behind them, lost in the crowd, unhappy, while to one out of a million…comes a bright destiny full of interest and meaning…For the bliss of being an actress I could endure want, and disillusionment, and the hatred of my friends, and the pangs of my own dissatisfaction with myself…I am so tired. If I could only rest…You cannot imagine the state of mind of one who knows as he goes through a play how terribly badly he is acting. I am a sea-gull — no — no, that is not what I meant to say. Do you remember how you shot a seagull once? A man chanced to pass that way and destroyed it out of idleness. I feel the strength of my spirit growing in me every day. I know now, I understand at last, that…it is not the honor and glory of which I have dreamt that is important, it is the strength to endure…and when I think of my calling I do not fear life.

Now I am a devoted Chekhovian from a long line of devoted Chekhovians, but it has never been less than a struggle for me to admit that Chekhov, despite his prodigious talent and the pains he went to “to get the sound right,” was certainly guilty of allowing his authorial presence to overwhelm a character. To me, Nina’s speech less resembles that of a naïve 19-year-old than the domineering, 35-year-old, world-weary, consumptive male, so much so that I’m not entirely convinced that Chekhov, consistently ahead of his time, wasn’t making some entirely other kind of meta-textual joke.

Now I am a devoted Chekhovian from a long line of devoted Chekhovians, but it has never been less than a struggle for me to admit that Chekhov, despite his prodigious talent and the pains he went to “to get the sound right,” was certainly guilty of allowing his authorial presence to overwhelm a character. To me, Nina’s speech less resembles that of a naïve 19-year-old than the domineering, 35-year-old, world-weary, consumptive male, so much so that I’m not entirely convinced that Chekhov, consistently ahead of his time, wasn’t making some entirely other kind of meta-textual joke.

Or maybe he just blew it. Getting dialogue right has never been easy. Even the ancients, unburdened by modern conventions of verisimilitude, had their reasons for being concerned with making the text sound right. For modern authors, this task has come down in the form of a necessity to capture the patterns of ephemeral speech in physical form in such a way that it might, at least, suggest authenticity, plausibility, durability. The plain fact is that if it doesn’t sound real, how many modern readers will bother to venture beyond page two?

But what tack to follow when one encounters literature — celebrated literature — that presents itself as fact but sounds like so much fiction?

“We had an Invalids’ Home in our town. Full of young men without arms, without legs. All of them with medals. You could take one home…they issued an order permitting it. Many women yearned for masculine tenderness and jumped at the opportunity, some wheeling men home in wheelbarrows, others in baby strollers. They wanted their houses to smell like men, to hang up men’s shirts on their clotheslines. But soon enough they wheeled them right back…They weren’t toys…It wasn’t a movie. Try loving that chunk of man.”

So who is that? Kurt Vonnegut? W.G. Sebald? Kōbō Abe?

When 2015 Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich began writing her cycle on Soviet history, variously referred to as “Voices from Utopia” or “A History of Red Civilization,” she had little idea of what she was getting into. As she recounted in a recent talk, “it wasn’t until finishing up my interviews for ‘The Last Witnesses’ [not yet available in English translation] that I understood what I was describing with this approach. I wanted to write about this paradise, in the Russian understanding of it.”

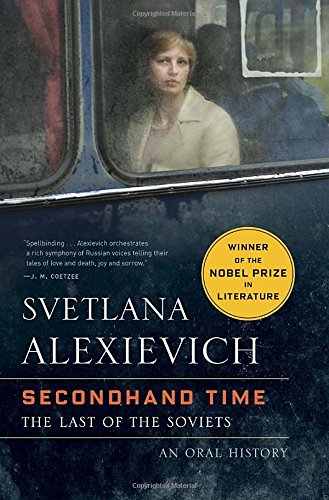

This week, Alexievich’s most recent book Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets was released in the United States, taking its place in an estimable lineup of work whose telos it is to capture the sense and nonsense of the Soviet Union. Other titles of this pedigree include notably, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, and Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. And yet, despite those novels’ indispensability for a fuller understanding of Soviet history, neither the metered didacticism of the former nor the engaging casual authority of the latter achieve the effect of Alexievich’s collage of first-hand testimony in Secondhand Time (the fifth and final volume in her Red Civilization series, though only the fourth to appear in English translation).

This week, Alexievich’s most recent book Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets was released in the United States, taking its place in an estimable lineup of work whose telos it is to capture the sense and nonsense of the Soviet Union. Other titles of this pedigree include notably, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, and Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. And yet, despite those novels’ indispensability for a fuller understanding of Soviet history, neither the metered didacticism of the former nor the engaging casual authority of the latter achieve the effect of Alexievich’s collage of first-hand testimony in Secondhand Time (the fifth and final volume in her Red Civilization series, though only the fourth to appear in English translation).

Alexievich, it turns out, has different rocks to turn over. Her text ranges wide, and never has utopia appeared quite so dystopian as it does in the recorded witness of the disenfranchised, the embittered, the deceived, and the delusional that inhabit these pages. Her method is that of seeker, itinerant. She wanders the blasted and ill-remembered territories of the former USSR, encountering a host of characters — dime-store philosophers, ex-military, ex-State security turned private consultant, the rural poor, and memorably, a raft of widows unhinged by the injustice of their loss — but each with a tale to tell and bread to break. It is these communal interactions, these simple lives, that give her oral history of dysfunction its heft. In this way Alexievich helps make sense of a situation as impossible to explain as it is to deny.

This urgency to assist us in grasping the Soviet conundrum comes across nowhere so effectively as in one particularly idiosyncratic mode of Alexievich’s reporting in Secondhand Time. Here she includes longish sections of seemingly scattershot testimony, unreferenced and decontextualized, presented rapid-fire, as if she were simply regurgitating what she heard while walking through a crowded railway station, jotting down overheard snippets of conversation, allowing herself a liberal dose of ellipses to reflect the bits she didn’t quite catch.

‘The devil knows how many people were murdered, but it was our era of greatness.’ — ‘I don’t like the way things are today…but I don’t want to return to the sovok, [discredited, retrograde “Soviet way” of thinking & living] either. Unfortunately, I can’t remember anything ever being good.’ — ‘I would like to go back. I don’t need Soviet salami, I need a country where people were treated like human beings.’ — ‘There’s only one way out for us — we have to return to socialism, only it has to be Russian Orthodox socialism. Russia cannot live without Christ.’ — ‘Russia doesn’t need democracy, it needs a monarchy. A strong and fair Tsar. The first rightful heir to the throne is the Head of the Russian Imperial House, the Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna…’

These sections, subtitled “Snatches of Street Noise and Kitchen Conversations” go on for pages, like the graphomaniacal, rambling thesis of some importunately zealous, nicotine-oozing Marxist — and Fulbright hopeful — theater arts student from Lugansk. And while the collective dissonance of these quotations might rightly clang on the Western ear, to me they sound like home. The complaints, the confusion, the grasping for meaning recorded in these pages could have been lifted, verbatim, from conversations I’ve had around Kyiv with an old landlady, a wannabe capitalist rainmaker, a frighteningly accessorized Orthodox pilgrim, or a nicotine-oozing Marxist theater arts major…

Like the improbably warped and yet wonderfully apt associations that spilled out of Chekhov’s imagination, the reporting in “Secondhand Time” makes extraordinary demands of the reader, while offering — to the patient reader — insight otherwise unavailable into what made the Soviet clock tick, albeit counterclockwise. This is a book rendered meaningful, rendered necessary, because of the difficulties it presents and the contradictions it documents. Its truth lies in the resolute confusion and resultant collective cognitive dissonance captured by Alexievich, and in her refusal to pronounce judgment on even a word of it.

Secondhand Time is a strong closing act to Svetlana Alexievich’s five-book cycle chronicling the last days of the Soviet Union, and of the effects of a dispirited socialism and cynical political apparatus on the lives of the Soviet rank and file. In contrast to her previous work, the absence of a single defined subject — Chernobyl, Afghanistan, Women in War — results in a book that is certainly less focused, but no less disturbing than her earlier histories.

Seventy years of Soviet socialism has given birth to the homo sovieticus, and if Alexievich accomplishes anything here, it is to alert us to his existence, as well as to the grave error involved in the summary dismissal of his complaint, or graceless satisfaction at his profanation. She takes the jingoish caricature, the pulp-fiction rogue, the faceless millions of victims of historical record, and restores to them a voice — their own.

Like Chekhov, Svetlana Alexievich is an author who writes in Russian though does not self-identify as such. She is a messenger of no particular fealty save that owed to her story. Her body of work leaves us with more than a dry history of a time, a place, a people, but with a document composed of living breath. Breathing it in, we are compelled to clasp our hat to our head and set off to nudge, to jolt, and to buffet our way through crowds of former Soviet citizens — Russians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Buryats, Tajiks, Latvians, Georgians — at the Kyiv, Novosibirsk, or St. Petersburg vogzal and off toward our train.

And perhaps, climbing aboard, we see there in our coupe a fair-haired young woman wearing a beret, a small dog on her lap, her luggage marked with the name of her country estate at L____________…