“There are two sound ways for a girl to deal with a young man who is insistent. She can marry him, or she can say ‘No.’” — Ladies’ Home Journal, May 1961

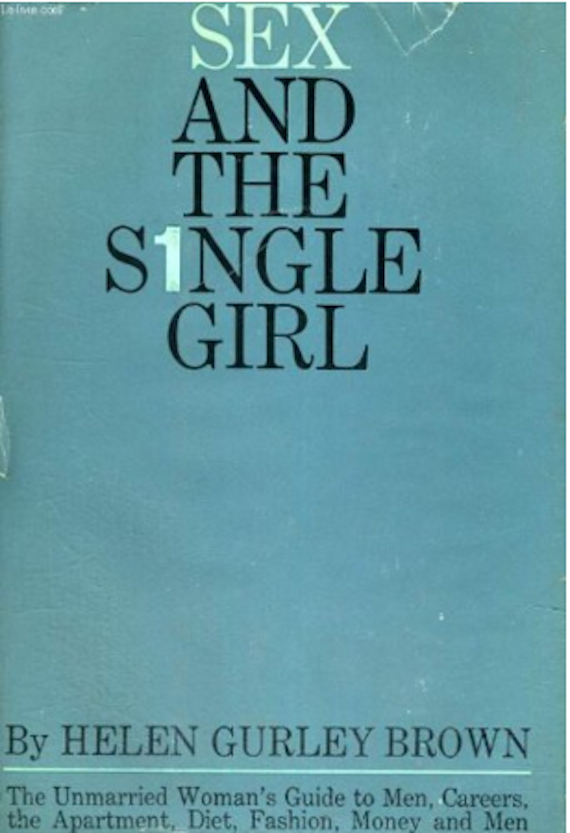

In 1962, a 40-year-old woman published a guide for single girls that shocked a nation (and spawned future memoir-manuals.) The author was Helen Gurley Brown, and the book was Sex and the Single Girl: The Unmarried Woman’s Guide to Men, Career, the Apartment, Diet, Fashion, Money and Men.

Racy title aside, the simple teal-blue book jacket was far from flashy — if anything, it looked like a secret handbook. But the message inside was loud and clear, and Helen megaphoned it to the world: Single girls had sex, and often with multiple partners before marriage. Why pretend otherwise? “Should a man think you are a virgin?” she asked in one chapter. “I can’t imagine why, if you aren’t. Is he? Is there anything particularly attractive about a thirty-four-year-old virgin?”

Drawing from her years of experience as a penny-pinching bachelorette in Los Angeles, Helen gave single women advice on everything from keeping a budget and finding an apartment to wearing makeup, meeting men, and staging a successful affair — she’d survived plenty of trysts with married men — but she was no longer single herself. She was comfortably married to the editor and movie producer David Brown, who had conjured up the idea for the book in the first place, and her status as Mrs. Brown was the ultimate testament to the fact that her man-trapping tips really worked, at any age.

Though Sex and the Single Girl had no shortage of critics (Robert Kirsch of the Los Angeles Times called it “as tasteless a book as I have read this year”), it was an instant bestseller, generating a multimillion-dollar franchise that included an eponymous movie (starring Natalie Wood and Tony Curtis); a nationally syndicated column, “Woman Alone,” written by Helen and aimed at single girls; a recorded album called Lessons in Love, which offered gems like “How to Talk to a Man in Bed;” a second book, Sex and the Office; and, of course, a magazine, the new Cosmopolitan, which Helen revamped from a staid general-interest title into a sexy single girl’s bible in 1965.

Though Sex and the Single Girl had no shortage of critics (Robert Kirsch of the Los Angeles Times called it “as tasteless a book as I have read this year”), it was an instant bestseller, generating a multimillion-dollar franchise that included an eponymous movie (starring Natalie Wood and Tony Curtis); a nationally syndicated column, “Woman Alone,” written by Helen and aimed at single girls; a recorded album called Lessons in Love, which offered gems like “How to Talk to a Man in Bed;” a second book, Sex and the Office; and, of course, a magazine, the new Cosmopolitan, which Helen revamped from a staid general-interest title into a sexy single girl’s bible in 1965.

The original Sex and the Single Girl also inspired countless imitations, among them a cookbook, Saucepans and the Single Girl (“Guaranteed to do more for the bachelor girl’s social life than long-lash mascara or a new discotheque dress,” it promised), Sex and the Single Man, and Sex and the Single Cat. “A publisher asked me to write a ‘me-too’ book — about sex and the college girl,” Gloria Steinem told me in a recent interview. She declined, but future food critic Gael Greene took on the task of reporting from the real frontlines of the sexual revolution: the nation’s college campuses. Her book, Sex and the College Girl, hit shelves in 1964.

The original Sex and the Single Girl also inspired countless imitations, among them a cookbook, Saucepans and the Single Girl (“Guaranteed to do more for the bachelor girl’s social life than long-lash mascara or a new discotheque dress,” it promised), Sex and the Single Man, and Sex and the Single Cat. “A publisher asked me to write a ‘me-too’ book — about sex and the college girl,” Gloria Steinem told me in a recent interview. She declined, but future food critic Gael Greene took on the task of reporting from the real frontlines of the sexual revolution: the nation’s college campuses. Her book, Sex and the College Girl, hit shelves in 1964.

Along with guidebooks for single girls, there were also stern warnings. In 1963, two young, unmarried women were murdered in their apartment on the Upper East Side; one had been a Newsweek copy girl, the other a teacher. The high-profile double homicide was dubbed the Career Girl Murders, and it terrified thousands of single, working girls across New York City. It also inspired a morose 125-page safety manual, Career Girl, Watch Your Step!, written by Max Wylie, the father of one of the victims, who cautioned the Sex and the Single Girl set about the dangers of dating and living alone in the big city.

There’s no doubt that Helen Gurley Brown deserves credit for ushering in the sexual revolution and singles culture, but she was hardly the first woman to tackle writing a cheeky, charming guide for bachelorettes. Five decades earlier, in 1909, Helen Rowland, a noted satirist who penned biting aphorisms about the battle of the sexes for the New York World newspaper, collected her columns into an illustrated book of epigrams titled Reflections of a Bachelor Girl. (She began the column after the demise of the first of her three marriages.) Rowland followed up with more books, including A Guide to Men, published in 1922 — the era of the flapper, with her short skirts, bobbed hair, loose morals, and penchant for cigarettes and petting parties.

That year, Helen Gurley Brown was born in the small town of Green Forest, Ark. She grew up during the Great Depression, when wives and widows flooded the workforce, taking on jobs once meant for their husbands. Necessity paved the way for a new breed of woman who was capable of taking care of herself, and didn’t have to rely on a man — and popular culture reflected her newfound independence. In the summer of 1936, when Helen was 14, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind topped the bestseller lists, as the nation fell in love with a flawed and fiercely determined heroine named Scarlett O’Hara. The same year, a Vogue editor named Marjorie Hillis published a self-help guide for single women titled Live Alone and Like It: A Guide for the Extra Woman.

That year, Helen Gurley Brown was born in the small town of Green Forest, Ark. She grew up during the Great Depression, when wives and widows flooded the workforce, taking on jobs once meant for their husbands. Necessity paved the way for a new breed of woman who was capable of taking care of herself, and didn’t have to rely on a man — and popular culture reflected her newfound independence. In the summer of 1936, when Helen was 14, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind topped the bestseller lists, as the nation fell in love with a flawed and fiercely determined heroine named Scarlett O’Hara. The same year, a Vogue editor named Marjorie Hillis published a self-help guide for single women titled Live Alone and Like It: A Guide for the Extra Woman.

Who exactly was this Extra Woman, or E.W., as The New York Times later dubbed her? She was a woman who earned her own money and liked to spend it, and to reach her, Hillis’s publisher, Bobbs-Merrill, ventured far beyond the bookstore to places where single women congregated. “They sent their salesmen to department stores around the country with a multi-page memo that outlined how to pair quotations from the book with items from the store, like negligees and pajamas, compact furniture, and cosmetics,” says Joanna Scutts, who is currently working on a book about Hillis, The Extra Woman. “Hillis was resolutely a believer in material pleasure, beautiful objects, and the comforts of surrounding yourself with the things you loved.” (Three decades later, Helen Gurley Brown’s publicity team pitched Sex and the Single Girl to boutiques, singles resorts, and secretarial schools. In L.A., one bookstore’s window display featured the guide, opened to the chapter “How to Be Sexy,” paired with a black bikini.)

In many ways, Hillis’s books and their offbeat promotion offered a valuable blueprint for Helen Gurley Brown, with one major exception: Live Alone and Like It spoke primarily to a savvy, city-dwelling reader, while Sex and the Single Girl addressed a far simpler creature. It was meant for the plain, small-town girl — or “mouseburger,” to use Helen’s famous coinage — who might have aspired to be more like Hillis’s sophisticated reader, or Hillis herself, only with a much more active sex life. (A minister’s daughter from Brooklyn, Hillis had pragmatic attitudes about sex but didn’t obsess over it, or men, the way Helen did.)

Still, despite their differences, both authors recognized that the so-called problems faced by single women could actually be assets, even enviable luxuries. Long before Helen declared the working single woman as “the newest glamour girl of our time,” Hillis addressed her with a cut-the-bullshit approach. Might as well face it: “An extra woman is a problem…Extra women mean extra expense, extra dinner-partners, extra bridge opponents, and, all too often, extra sympathy,” she wryly observed in her first chapter, “Solitary Refinement.” And yet, the right attitude could turn it all around.

Being a “live-aloner” had its perks: namely, total freedom. Without a man of the house to serve, a woman could tend to herself, breakfasting in bed, basking in her nightly beauty ritual, and best of all, she could have her own bathroom, “unquestionably one of Life’s Great Blessings,” Hillis wrote. Like a witty, worldly aunt, Hillis doled out bon mots on other subjects like decorating a modern apartment for one, mixing a classic Manhattan, and the importance of having a chic bedroom wardrobe. “We can think of nothing more depressing than going to bed in a washed-out four-year-old nightgown,” she noted, “nothing more bolstering to the morale than going to bed all fragrant with toilet-water and wearing a luscious pink satin nightgown, well-cut and trailing.”

Hillis also leveled with the legions of single women about the pros and cons of sex outside of marriage, and having an affair. “Certainly, affairs should not even be thought of before you are thirty,” she wrote. “Once you have reached this age, if you will not hurt any third party and can take all that you will have to take — take it silently, with dignity, with a little humor, and without any weeping or wailing or gnashing of teeth — perhaps the experience will be worth it to you. Or perhaps it won’t.”

In 1937, Hillis published Orchids on Your Budget, predating Helen Gurley Brown’s practical financial advice for single girls, followed by Corned Beef and Caviar for the Live-Aloner — a recipe book that might have inspired Helen’s later Single Girl’s Cookbook — and New York Fair or No Fair, a travel guide for women headed to the 1939 World’s Fair. (The same year, at the age of 49, Hillis shocked her readers by marrying Thomas H. Roulston, a wealthy widower who owned a chain of grocery stores, and moving to Long Island.)

Most of these single-girl guides have gone the way of the chastity belt, but in the spirit of HGB, here are some of the wittiest and weirdest, along with some choice advice — take it or leave it.

Title: The Young Lady’s Friend (1880)

Written By: Mrs. H.O. Ward, compiler of “Sensible Etiquette”

Written For: Proper young ladies of America

On Keeping Cool: “The less your mind dwells upon lovers and matrimony, the more agreeable and profitable will be your intercourse with gentlemen.”

Title: Advice to Young Ladies from The London Journal of 1855 and 1862 (published in 1933)

Selected By: R.D., from the weekly columns of “Notice to Correspondents”

Written For: Proper young ladies of England

On Coquetry: “Flirting is heartless and unprincipled; it leads to callousness in other respects, sullies the female mind, provokes retaliation, and is sure to end in heart-burnings, sorrows, and too frequently disgrace.”

Title: Reflections of a Bachelor Girl (1909)

Written By: Helen Rowland, columnist for the New York World who became known as “the female Bernard Shaw”

Written For: Men and women wanting a good laugh

On the Importance of Taking the Long View Before Taking a Vow: “Before marrying a man, ask yourself if you could love him if he lost his front hair, went without a collar, smoked an old pipe, and wore a ready-made suit; all of these things are likely to happen.”

Title: Live Alone and Like It (1936)

Written By: Marjorie Hillis, Vogue editor

Written For: Single career girls in the city

On Ladies and Liquor: “There is no simpler way of entertaining successfully than having a cocktail party, and there is no surer way of making a casual guest have a good time, than serving a highball. For breaking ice, mixing strangers, and increasing popularity, alcohol is still unrivaled.”

Title: Orchids on Your Budget (1937)

Written By: Marjorie Hillis

Written For: Style-conscious live-aloners with limited funds

On Fashion Sense: “A cheap dress worn with good accessories will fool more people than an expensive dress worn with cheap accessories.”

Title: Sex and the Single Girl (1962)

Written By: Helen Gurley Brown

Written For: Small-town girls thinking of moving to the big city for romance and recognition

On How to Meet a Man: “Carry a controversial book at all times — like Karl Marx’s Das Kapital or Lady Chatterley’s Lover. It’s a perfectly simple way of saying, ‘I’m open to conversation,’ without having to start one.”

Title: Career Girl, Watch Your Step! (1964)

Written By: Max Wylie, father of career-girl murder victim Janice Wylie

Written For: The Sex and the Single Girl set

On Bachelorettes in the Big City: “Don’t think of yourself as being safe. Think of yourself as being in danger all the time. This will make you wary. There is no better protection than an awareness of the dangers that might engulf you.”

Title: Saucepans and the Single Girl (1965)

Written By: Jinx Morgan and Judy Perry, college roommates-turned-cookbook authors

Written For: Unmarried women looking for the fastest way to a man’s heart

On Cooking for the Man in a Brooks Brothers Suit: “If you can cook without tripping over it, by all means wear your chicest hostess skirt. This is known as packaging the product.”

Title: Helen Gurley Brown’s Single Girl’s Cookbook (1969)

Written By: Helen Gurley Brown

Written For: Cosmo Girls

On Ending the Affair: “When it comes to that dinner you know in your heart is to be the longed-for (on your part) last one, you must plan as wickedly as for a lovers’ feast. It shouldn’t be too difficult. Through careful observation of your companion through the months or years you’ll know everything he actively hates — what gives him tummy cramps or causes him to break out. These are the foods you carefully prepare and feed him tonight.” Suggested dishes: Ceviche, Lamb Kidneys and Bacon, Refritos with Cheese.