I wrote my last Year in Reading when I was about to have a baby, and now the baby is here. In accordance with all platitudes, the year has gone by very quickly, and yet its component moments were glacial, with a glacier’s way of doing a lot while appearing to do very little. Richard Ford, whose novels I re-read just before the baby came, divided Frank Bascombe’s life into the Existence Period, the Permanent Period, and the Authentic Self. My year comprised three epochs which were, more or less, 1) Magic, 2) Bad, 3) Decisive. The Magic Period was all soft blankets and endless afternoons in the nest and long, slow walks across the city. The Bad was clumps of hair like hamsters in the bathtub, and tiny plastic pump pieces, and vanished milk, and finding myself on lunch break smoking cigarettes in a shrub. Then, perhaps as a consequence of this period, came a time for making plans. Motherhood is not unlike drugs in that it has caused me to question the arrangements of life in even its most privileged iterations. “Why should people go to a desk and sit in front a computer and write emails all day,” I would say to my husband, like a very young, very high person.

I suppose the thing that most characterized the year, apart from the presence of the baby herself, is an overall failure to modulate, some mechanism gone haywire, so that seeing someone with a bag on a seat on a crowded train made me want to scream “The bag doesn’t get a seat!” out of all proportion. When a series of administrative fuckups created a reversible but maddening problem with my maternity leave, I felt my rage could electrify a small village. I noticed the other day that a Vanity Fair I bought in an airport seven months ago is still sitting on our coffee table, because I’ve become strangely obsessed with ensuring my husband reads an article by William Langewiesche about commercial space flight. “You’ve got to read this amazing story — you’ll love it!” I keep telling him, and Robin Wright gazes serenely from the cover, asking me whether I need to talk to somebody.

How to describe a year where I felt simultaneously so powerless and so powerful — when the prospect of buying a stamp or fully participating in electoral democracy seemed insurmountably difficult, but writing a book seemed possible. Or moving to a new place. Or having another baby. When I felt so inept at the womanly art of taking care of my appearance, but so unexpectedly okay at taking caring of the baby (she is what they call an easy baby; I know it could have gone any number of ways). How strange it was to go to work and long to be with her; to long for solitude in her presence.

I know that I read a lot this year, but I can remember almost nothing, and what I remember is tied to the epochs outlined above. Like most efforts at periodization, things fall apart when you begin serious excavations. There was plenty of magic distributed through the year; it smiled in the winter and laughed in the spring and crawled in the summer and stood up in the fall. And the Magic Period, if I think about it, was actually marked by frequent crying episodes (mine, not the baby’s), like little bursts of rain against the roof. But like rain in California — and it actually did rain, those first few weeks of her life — there was something nourishing and necessary about the jags. During that period I read Mating, and whether it was the time or the book I don’t know but it’s one of my favorite things I’ve ever read. I loved it so much that I immediately tried to write a novel in its image, but fortunately realized, somewhere around the third paragraph, that it wasn’t a very good idea. I read Elisa Albert’s After Birth, and even though it was before my own rage came home to roost, I felt the force of her beleaguered, gimlet-eyed narrator.

I know that I read a lot this year, but I can remember almost nothing, and what I remember is tied to the epochs outlined above. Like most efforts at periodization, things fall apart when you begin serious excavations. There was plenty of magic distributed through the year; it smiled in the winter and laughed in the spring and crawled in the summer and stood up in the fall. And the Magic Period, if I think about it, was actually marked by frequent crying episodes (mine, not the baby’s), like little bursts of rain against the roof. But like rain in California — and it actually did rain, those first few weeks of her life — there was something nourishing and necessary about the jags. During that period I read Mating, and whether it was the time or the book I don’t know but it’s one of my favorite things I’ve ever read. I loved it so much that I immediately tried to write a novel in its image, but fortunately realized, somewhere around the third paragraph, that it wasn’t a very good idea. I read Elisa Albert’s After Birth, and even though it was before my own rage came home to roost, I felt the force of her beleaguered, gimlet-eyed narrator.

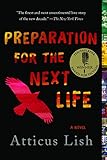

As my milk dried up and the Bad Period began, I read Beloved and Preparation for the Next Life, and they were vivid and perfect, although they didn’t make me feel less blue. I read The Ghost Network, which has as its heroine a Lady Gaga figure, and because of it I listened to Lady Gaga on purpose for the very first time. There was a stretch of about a week when I couldn’t bring myself to climb the hill to my office without blasting the song “Do What U Want,” imagining myself pirouetting up the road like someone in a training montage. I mentioned how much I liked the song to a friend, who said, “It sucks that it’s R. Kelly”; I hadn’t realized that it was R. Kelly, who is known for doing what he wants with the bodies of underage women, and I understood then that verily there are no pure pleasures.

I read so many sad things this year, and felt that life itself has a failure to modulate. I read Aleksandar Hemon’s essay “The Aquarium,” about his daughter, and my friend Katie Coyle’s essay about hers. Sad things so generously written have a way of momentarily recalibrating the haywire apparatus, so that it registers, These are the real things — not bags on the seat, not misfired paperwork. But it’s not as if there’s comfort in the suffering of others; hugging your own family close only illuminates the supremely inequitable hazards of existence. Reading the news has, of course, been unspeakable, when every drowned child and murdered child assumes the characteristics of your own, and it feels like all there is to do is watch events unfold on a chyron, and read Facebook posts.

As I clambered toward the Decisive Period I read Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart, which is out next year and which is breathtaking. I read J.M. Ledgard’s “Terra Firma Triptych,” also breathtaking in the very particular and somewhat confounding way of J.M. Ledgard (he seems to also be a person who has reached a decisive moment, but whereas mine was, “I should quit my job and write things,” he schemes to build drone ports across rural Africa, and has evidently arranged his life thus). I read a stirring article about small-boned women and ancient cousins who bury their dead. Finally, I picked up Elena Ferrante’s first Neapolitan novel, which I had once put aside after a dozen pages, and discovered that she was exactly who I needed to read: a woman writing about women, their ugliness and their ambition and their promise and their rage — their utter humanity. I ripped through the remaining volumes. You’d think a cheerful book would be the thing to pull me out of my funk, but I needed something pitiless, something about the messy arrangements of life, something about a writer trying to “imitate the disjointed, unaesthetic, illogical, shapeless banality of things,” and failing up into something vital and perfectly-formed — more lifelike, somehow, than life itself.

As I clambered toward the Decisive Period I read Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart, which is out next year and which is breathtaking. I read J.M. Ledgard’s “Terra Firma Triptych,” also breathtaking in the very particular and somewhat confounding way of J.M. Ledgard (he seems to also be a person who has reached a decisive moment, but whereas mine was, “I should quit my job and write things,” he schemes to build drone ports across rural Africa, and has evidently arranged his life thus). I read a stirring article about small-boned women and ancient cousins who bury their dead. Finally, I picked up Elena Ferrante’s first Neapolitan novel, which I had once put aside after a dozen pages, and discovered that she was exactly who I needed to read: a woman writing about women, their ugliness and their ambition and their promise and their rage — their utter humanity. I ripped through the remaining volumes. You’d think a cheerful book would be the thing to pull me out of my funk, but I needed something pitiless, something about the messy arrangements of life, something about a writer trying to “imitate the disjointed, unaesthetic, illogical, shapeless banality of things,” and failing up into something vital and perfectly-formed — more lifelike, somehow, than life itself.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.