1.

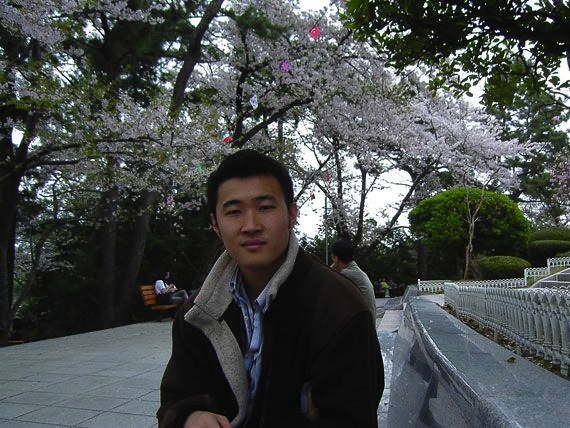

When I was 23, I returned to Korea for the first time since my adoption. For a month, I lived in a love motel, in a room paid for by the school at which I taught. I ate almost nothing but Frosted Flakes. I tried to gather the courage to give up and fly back to America. The only thing holding me there was the Korean woman who would become my wife, whom I met and began dating almost immediately.

I have been told by other writers that this story should be a book. Yet I have never felt like it has enough weight on its own. It is an interview anecdote: the 20 pounds I lost over two weeks with Tony the Tiger, the red lights ringing the ceiling over my round bed, the way my wife saved me, my denial over why I was really there. But something in the story has always been lacking.

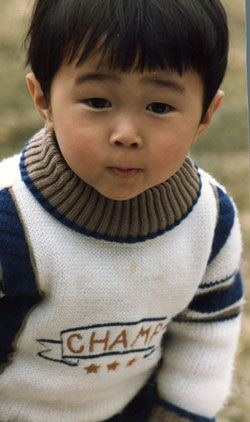

Perhaps what is missing is a part I haven’t wanted to tell, a part other writers could see hidden in the whole, the same part that I have always struggled with confronting and have never known enough about: the two years I spent in Korea as a baby, before I was adopted as a sickly toddler who couldn’t toddle or talk.

2.

Recently I designed a course on the novel for Grub Street, a writing center in Boston. The first thing I did was to get down from my shelves 10 novels I love, in search of scenes we might emulate. The goal for the course is to write six scenes, half of the 12 “major scenes” I heard it said once, in a workshop at Bread Loaf, that make up a typical contemporary novel. This “fact,” of course, made it into my sparse notes, though I didn’t know what to think about it. It provided a seductive kind of answer.

The first type of scene I went looking for was the “inciting incident,” the scene that starts the plot on its course. But what I noticed very quickly was that what starts the plot on its course is not usually what incites a novel, as we typically think of it. In other words, the scene that starts the plot isn’t usually the why of a novel’s existence in place and time, the situation of the story: think Nick moving to New York in The Great Gatsby, or the train going into the lake in Housekeeping. Those are incidents that might contribute to plot on a thematic and foundational level — nothing in those two great novels could have happened otherwise — but that don’t directly contribute to the string of causation E.M. Forster defined as plot (“The king died, and then the queen died of grief”).

The first type of scene I went looking for was the “inciting incident,” the scene that starts the plot on its course. But what I noticed very quickly was that what starts the plot on its course is not usually what incites a novel, as we typically think of it. In other words, the scene that starts the plot isn’t usually the why of a novel’s existence in place and time, the situation of the story: think Nick moving to New York in The Great Gatsby, or the train going into the lake in Housekeeping. Those are incidents that might contribute to plot on a thematic and foundational level — nothing in those two great novels could have happened otherwise — but that don’t directly contribute to the string of causation E.M. Forster defined as plot (“The king died, and then the queen died of grief”).

3.

About three months into my time in Korea, after I had changed jobs and decided to stay, my wife-to-be asked if I wanted her to help me find my birth mother. She could look into various Korean channels, search places I would never be able to search on my own. The offer she made was this: she would do everything and when she found a clue, we could travel together and she would translate for me. I thought about her offer for weeks, while she waited for me to make up my mind. I didn’t want to upset my family, but it was true that I didn’t have to tell them. I didn’t know how long my relationship would last, so I thought selfishly that this might be my best chance. On the other hand, I had been telling myself that I was not in Korea to find out anything about my birth family or my adoption, and this would change that. It would, I saw once I made up my mind, be admitting my denial.

I had my adoption information because I had needed it to get a new visa for former Korean citizens who had lost their citizenship (i.e. not by choice). Mainly, adoptees. The visa made it possible for me to do almost anything a citizen can do, except vote. My wife referred to the visa as an apology to adoptees when she told me about it and helped me to get my papers together.

She went ahead contacting whatever organizations she could find that still existed 21 years later. Eventually, she got a lead, and we made the trip to Seoul to meet with a person I thought would tell me about my birth mother, but who never would.

4.

A scene that might start a plot of causation is Gatsby asking Nick to set him up with Daisy. Or rather, Gatsby asking Jordan to ask Nick to set him up with Daisy, which mirrors the convoluted arrangement of cars and drivers that results in Gatsby taking the blame for killing Myrtle and subsequently being killed by Wilson in what is probably the novel’s climax. Gatsby’s inciting incident happens mostly “off-screen,” during Nick’s first attendance at one of Gatsby’s famous parties. The plot that begins here will bring Gatsby and Daisy back together and part them after the accident.

A simpler example, in a way, is the arrival of Sylvie in Housekeeping, Sylvie who will represent one way of dealing with the past (running away from it, or, rather, not dealing with it). Her “parenting” of Ruth and Lucille will result in them taking sides. Ruth will follow Sylvie out of town and Lucille will stay.

I am using my own story as an example because I want to talk about what I believe these incitations are doing. Why they come slightly later in the novel, and what purpose they serve structurally, what in general they incite.

5.

The offices of the adoption agency were in the basement of a concrete building which, from the outside, looked a lot like the sad little love motel I had recently vacated. My wife and I sat in a meeting room with a cheap couch, one chair that an agent would soon fill, and a coffee table on which my adoption file would appear. My memory goes in and out here, so I must leave the “truth” behind — such are the tools I am working with. It is likely that I have some sort of mental block regarding this trip, which makes me want to recreate it as better or worse than it actually was. I want to create a plot.

I opened a manila folder to find the application my parents had sent to adopt me. In it were shocking secrets about my father’s PTSD after Vietnam and my mother’s heartbreak over her inability to have a biological child. But, as my wife translated, there was nothing in the file about my birth mother. The agent said my birth mother had left me under a nearby bridge. I was found with a note that said, Give him to someone rich. A policeman gave me a name and took me to an orphanage, but the orphanage had recently burned down, so it, like my birth mother, was unrecoverable. My wife questioned none of this. I didn’t question it, either. I had new insight into my adoptive parents, which seemed itself a great treasure. What I wanted to know was whether I could photocopy the file. I was not allowed.

Later I would find out from other adoptees that they were told similar stories: of orphanages that no longer exist, of utter abandonment, and yet after going through a detective or lawyer or policeman, they were able to find much more, hidden or lost. I knew nothing about that then.

As the agent was gathering everything back up, though, absentmindedly, ready to put us behind her, I spotted a post-it note stuck to the folder. It had gone unseen, hidden against the table. As the folder lifted away, I snatched the note off of it and dropped it in my lap as if I was brushing away a fly, or as if I just wanted to touch my file one last time. The agent smiled at me as if she could understand this urge and had seen it before.

6.

In thinking about the architecture of inciting incidents, it may be useful to work my way backward from the climax.

I have heard it said that modern novels don’t “resolve,” but I don’t believe it. What may give the impression that the modern novel does not “resolve” is Nick leaving New York in a similar physical and financial state (himself) as when he found it, or Ruth and Sylvie walking across the bridge to another life we barely hear about. These are not the definitive endings of Shakespearean plays — there is no marriage or sweeping death — or Greek plays — there is no intervention from a god or interpretation from a chorus. Neither are they the end of Jane Eyre, where Jane finds her way back to a diminished Rochester, or the end of Age of Innocence, where we skip ahead many years to see that Archer’s choice (of how to live) was indeed permanent, or the end of Anna Karenina, where Anna throws herself under a train and Levin comes to religion, one forever unhappy and one forever happy. But there is a death in Gatsby, and there is a decision about how to live in Housekeeping. What is interesting to note is that these points constitute not the endings of those books but their likely climaxes. They are not the final images — the final images are more mysterious, are more: images. The green light at the end of the dock, or walking over the lake in which Ruth’s ancestors perished.

I have heard it said that modern novels don’t “resolve,” but I don’t believe it. What may give the impression that the modern novel does not “resolve” is Nick leaving New York in a similar physical and financial state (himself) as when he found it, or Ruth and Sylvie walking across the bridge to another life we barely hear about. These are not the definitive endings of Shakespearean plays — there is no marriage or sweeping death — or Greek plays — there is no intervention from a god or interpretation from a chorus. Neither are they the end of Jane Eyre, where Jane finds her way back to a diminished Rochester, or the end of Age of Innocence, where we skip ahead many years to see that Archer’s choice (of how to live) was indeed permanent, or the end of Anna Karenina, where Anna throws herself under a train and Levin comes to religion, one forever unhappy and one forever happy. But there is a death in Gatsby, and there is a decision about how to live in Housekeeping. What is interesting to note is that these points constitute not the endings of those books but their likely climaxes. They are not the final images — the final images are more mysterious, are more: images. The green light at the end of the dock, or walking over the lake in which Ruth’s ancestors perished.

So is there a resolution if it comes in the climax and not at the end of the book, and what exactly is being resolved there? I think the answer is in the question: what is being incited by the inciting incidents?

7.

I met my birth mother on a cold January day in Seoul, with a wind full of coming snow. I hadn’t dressed warmly enough, and I have a problem with my ears where the wind makes them ache deep inside my head, so I was vibrating with pain and my wife was pressing my arm to keep me calm. I have never told anyone this. I never told my parents I even looked for my birth family. My birth mother was a short woman with a scar along her cheek-line, bright hurt eyes, a jutting chin, a wide, flat forehead. I wondered what the scar was from. I have mysterious scars on my legs and I wanted to ask her about them, whether they were from before she left me or whether, as I have always suspected, something happened to me in the orphanage, perhaps connected with my inability, at age two, to walk and talk. I didn’t ask. Instead, I did what seemed natural: shifted my feet awkwardly, tried to stay out of arms’ length, and cried.

My birth mother wanted to hug me, seemed sure about her feelings, whatever they were. But I wasn’t sure. I was still so damaged. I had hidden away any dream of this moment so far inside of me that it was a long, drawn-out process to pull my expectations, my fears and desires, back out into the open air. What I had for my birth mother was tears. I was glad my wife was there, and yet I wanted badly to be both alone with my birth mother and alone myself, so I could work out what I was feeling and let the feeling be more a reality than the person.

It doesn’t matter what we talked about, because we talked about nothing and everything, because we never talked, because what are words, really, what is real and what is made up?

8.

In Gatsby and Housekeeping, the plot that starts with the inciting incident — will Gatsby and Daisy recover their love; will Ruth and Lucille keep to their house/family (essentially)? — comes to some conclusion in the climax. What, then, are the components of that plot? One can make the case that it is the intersection of the past and the present. Therein lies the main storylines of the books — and, I found, of all of the books in my stack.

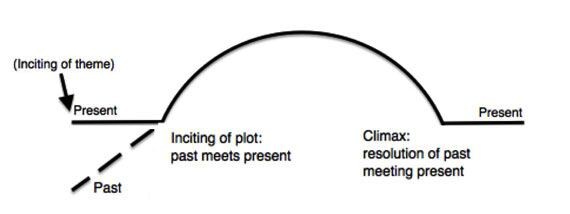

In the diagram below, I am trying to get at what I think of as not one but three inciting “incidents” in a “traditional” contemporary novel, and at the way they interact with each other. I am calling these incidents: the inciting of plot, the inciting of theme, and the inciting of the past.

The inciting of plot refers to the moment the past intersects with the present. It is Gatsby asking Jordan to ask Nick to set him up with Daisy. It is Sylvie appearing with her baggage (the same but different baggage as Ruth and Lucille), to take care of the sisters and the house.

The inciting of theme refers to the situation that starts the book. It is Nick moving to New York and relaying his father’s advice and his opinion of himself as judgment-free. It is Housekeeping’s haunting moment in which the grandfather’s train falls into the lake and affects the fabric of the town and the family.

The third inciting “incident” is something that happens in the past (the past in relation to the main plot). I am referring to this past as “inciting” because I want it to carry the definition of “to incite” in Merriam Webster: to move to action. The inciting of the past has to do with the way we employ backstory. Often it does not occur at the beginning of the book. In Gatsby, it is learning about Gatsby’s history with Daisy after the inciting of the plot. Though in Housekeeping, the inciting of the past is conflated with the inciting of theme and does, in fact, begin the novel.

The inciting of the past has a lot to do with how a novel resonates. Ruth and Sylvie walking over the bridge — an image that stuck in my mind for years after I first read Housekeeping and couldn’t remember where the scene came from — is haunting on its own, yet is far more haunting and powerful combined with the context of what happened to Ruth’s grandfather. A Gatsby who pursues an affair with Daisy without any prior relationship never gets Nick to that famous line of “boats against the current.”

9.

It was only after my birth mother had taken my wife and me back to her apartment that we understood what was written on that post-it note. I am making this up. My wife pressed my birth mother for more, as she had pressed the agency for more. Mother does not want reunion. Why had my birth mother told the agency that, or why had someone written it there and left it for me to find? Why was my birth mother acting the opposite now, as if she had always wanted to see me? I looked around the apartment as these two Korean women spoke the language of my birth, which I couldn’t understand. Their conversation, their lives, everything seemed so far away from me. It is a small room, and the clean, thin walls press close, but what those walls really are, borders between me and my past, are unbreachable still. I look up at the white florescent lights along the four edges of the ceiling, terrible lighting that makes everything seem as unreal as it is, as ugly as it could have been. It recalls the red lights in the love motel.

In the end, my birth mother told my wife that she had always been ashamed, and there were reasons, plenty of understandable reasons. She admitted that she was pretending and she would rather not do this, that she wasn’t ready for me yet. I let her, and will always let her, go.

10.

As an aside: a writer friend recently brought up the idea that this focus on some past loss is a very American approach to the novel, and I wonder about this. But it is not necessarily a focus on loss that I am after, but a focus on the power of the present when it has the echo of the past, whether lost or, in the case of The Sun Also Rises or No-No Boy, two of the other books I was looking at, never able to be attained.

As an aside: a writer friend recently brought up the idea that this focus on some past loss is a very American approach to the novel, and I wonder about this. But it is not necessarily a focus on loss that I am after, but a focus on the power of the present when it has the echo of the past, whether lost or, in the case of The Sun Also Rises or No-No Boy, two of the other books I was looking at, never able to be attained.

I don’t even think it necessarily has to be the past. The past here is just an easier go-to. In The Apothecary, another book on my list, it’s magic, an inherited imagination.

11.

When my wife and I were told at the adoption agency that my birth mother was unavailable, we went to the bridge where they said she had left me. It was an overpass. Cars went by overhead. We got out of our taxi and then walked down below. The road going under followed along a river or a stream, and seemed largely untraveled. I thought it would bring something back to me, or at least bring something up — but I felt nothing. There were two large water stains on the wall, and I thought, That was where she left me, though I had no proof or memory. Later I would question whether she left me there at all or whether that was only a convenient story. It might be said that I was lucky someone passed by and found me, and brought me to the police.

A lot of coincidence goes into creating a story without a plot.

Eventually we returned home and assessed our trip to Seoul. The evidence pointed to nothing for certain. I had come from a Korean woman, that was real. I could see in my own face always a little of her. In the mirror was still everything, all the nothing, that I knew about me. Yet at least I was really seeing myself, at last. I had fooled myself into thinking that I was in Korea to teach English to Korean kids, that I was only staying for my relationship, that I couldn’t eat anything but Frosted Flakes because I feared for my stomach and not for my identity.

I had an apartment now and not a room in a love motel. I looked up at the ceiling and there were no red lights. I had a girlfriend who had done everything to help me see myself. I still had my life to live, I mean. A change might have happened on that trip, past might have met present, but what I had to do next was keep living in Korea in the wake of something that had both ended and not ended.

12.

I tell my students I believe in the rule of threes. There is a power that comes from two things coming together and resonating with a third. One thing does not a story make, but two or three things may. I want to get at what gives a novel a sense of depth, of meaningful action, a sense of propulsion and a sense of resolution and yet continuance. There’s a good case to be made that it begins with beginnings.

13.

I made up a lot of the personal story that unfolds in this essay. A lot of it didn’t happen.

I was adopted when I was two. That much is true. I went back to Korea when I was 23. Whatever those first two years of my life were like does indeed always seem to be the missing link. But I had to make up some of the beginning in order to make up a middle and an end. Which has to do with inciting incidents.

That doesn’t matter, though. This story was, and is, real. The shame that I gave my imaginary birth mother is real. That shame is mine. And letting her go, I did that, I do that. Assessing all of the lacking evidence is a daily look in the mirror. Lately I worry that I missed my chance to find out one crucial incitation. Of course I have had to make up my beginnings before and will do so again. These are the things so important to the plot of who I am and to any plot of conviction and consequence — so important that they constantly draw us in: where the story starts, where the past and present meet, and what past is yet to come.