Not so long ago, Detroit tended to enter the popular imagination through one of three routes: pictures in coffee-table books, in art galleries, or on the Internet. You’ve seen those ubiquitous images of the city’s decline that fall under the banner of “ruin porn” — such default spectacles as the gutted Michigan Central Station and Packard plant, along with artfully sagging houses, abandoned offices carpeted with lovely moss, picturesque trees sprouting out of piles of discarded textbooks, once-lordly theaters full of parked cars, grassy pampas where proud neighborhoods once stood.

The vanguard of ruin porn were such books as The Ruins of Detroit by Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, Detroit Disassembled by Andrew Moore, and American Ruins by Camilo J. Vergara, which centered on Detroit but included Camden, N.J., Gary, Ind., and other poster children for urban blight. In addition to these glossy books, there have been a fair number of gassy ones, such as last year’s A Violent Embrace: Art and Aesthetics After Representation by Renée C. Hoogland, who yammers about “presentness” and “instantiations of the phenomenon of pictoriality as such.” Out of this post-grad gas, Hoogland does manage to produce at least one clear insight about why Detroit ruin porn is so potent and so ubiquitous:

The vanguard of ruin porn were such books as The Ruins of Detroit by Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, Detroit Disassembled by Andrew Moore, and American Ruins by Camilo J. Vergara, which centered on Detroit but included Camden, N.J., Gary, Ind., and other poster children for urban blight. In addition to these glossy books, there have been a fair number of gassy ones, such as last year’s A Violent Embrace: Art and Aesthetics After Representation by Renée C. Hoogland, who yammers about “presentness” and “instantiations of the phenomenon of pictoriality as such.” Out of this post-grad gas, Hoogland does manage to produce at least one clear insight about why Detroit ruin porn is so potent and so ubiquitous:

It seems safe to say, however, that it is not so much the stories of Detroit, but its images, the visual imprint of its ruins, the horrifying pictures of its material disintegration, that form the most abiding impression of the city today, not only in the United States but around the world.

Sad to say, she’s right. The facile visual shorthand of ruin porn has eclipsed nuanced narrative as a way of telling the complex story of Detroit. It doesn’t help that much of the verbal narrative has been journalism written by reporters who dropped in to do a story, then left. This drive-by posse didn’t do the city many favors. There has recently been a flowering of very fine books about Detroit — by Mark Binelli, Charlie LeDuff, Anna Clark, and others — but, as Hoogland pointed out, they don’t have the crack-pipe appeal of ruin porn’s fetishistic images.

The absolute nadir of ruin porn has to be a video from 2013, the Detroit segment of the Tracing Skylines sponsored by Red Bull. In this segment, freestyle skiers do stunts in, around and on top of abandoned buildings in Detroit. Sometimes these young white bros pause to fret about the presence of “sketchy crackhead” (i.e., black) characters lurking near their video shoot. They might steal our expensive cameras and ski gear! White boys cavorting in the bombed-out remains of America’s blackest city — it’s sickening and obscene.

John Gallagher, the insightful reporter and architecture critic for the Detroit Free Press, rightly lumped such works together as “those dreary celebrations of ruins that came into vogue a few years ago.”

Now, with the same astonishing swiftness that the city emerged from bankruptcy, Detroit has begun to go beyond ruin porn and take a different route to the popular imagination: movie screens. As Detroit native Mark Binelli has written, “Detroit’s brand has become authenticity.” Authenticity is one thing you cannot fake, and it may be the one thing filmmakers crave above tax breaks (which have been generous in Michigan but are now under severe political pressure by the Republican-controlled state legislature).

The recent burst of movies shot in Detroit do not merely use the city as a backdrop to establish authenticity; they use the city as a character, as a crucial part of each movie’s atmosphere. There are many Detroits, but the one that’s making its way onto movie screens today is dark and moody. These movies don’t focus on the cheap thrill of photogenic ruins; they focus on the far deeper beauty that dwells in the shadows.

Here are just four of the many recent movies that show how the Motor City moved beyond ruin porn to become an unlikely movie star:

1. Only Lovers Left Alive

In 2013, Jim Jarmusch came out with a vampire/hipster mash-up set in Detroit and Tangier, featuring a pair of too-cool-for-school vampires named Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton). He’s holed up in a gloomy mansion in Detroit’s once-opulent Brush Park, with his expensive guitars and vinyl record collection and a growing sense of despair at the folly of the human race; she’s at their second home in Tangier, reading Miguel de Cervantes and David Foster Wallace when she’s not copping super-pure blood from Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt), who’s still bummed, after all these centuries, that he didn’t get credit for writing the Bard’s stuff. You begin to get the idea that this movie isn’t about vampires so much as it’s about connoisseurs who have a heightened appreciation for art, music, and literature that surpasses that of mere mortals, who they deride as “zombies.” Which is to say it’s about people who, like Jim Jarmusch, are hip.

In 2013, Jim Jarmusch came out with a vampire/hipster mash-up set in Detroit and Tangier, featuring a pair of too-cool-for-school vampires named Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton). He’s holed up in a gloomy mansion in Detroit’s once-opulent Brush Park, with his expensive guitars and vinyl record collection and a growing sense of despair at the folly of the human race; she’s at their second home in Tangier, reading Miguel de Cervantes and David Foster Wallace when she’s not copping super-pure blood from Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt), who’s still bummed, after all these centuries, that he didn’t get credit for writing the Bard’s stuff. You begin to get the idea that this movie isn’t about vampires so much as it’s about connoisseurs who have a heightened appreciation for art, music, and literature that surpasses that of mere mortals, who they deride as “zombies.” Which is to say it’s about people who, like Jim Jarmusch, are hip.

Since Adam and Eve are vampires, the movie takes place entirely after dark. On blood-gathering missions, they drive through Detroit’s abandoned nighttime streets, occasionally passing a lone police car. The eeriness is nearly physical. The lovers do visit a ruin porn staple, the Michigan Theater, but the city doesn’t provide scenery so much as it provides atmosphere, a sense of limitless dread. When there’s nothing out there, anything is possible, and most of it is bad.

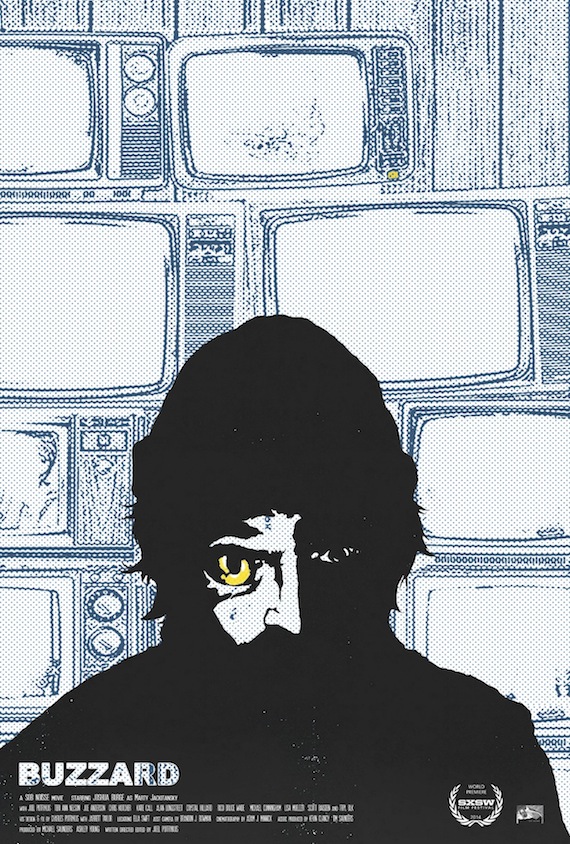

2. Buzzard

The sublimely repulsive Joshua Burge plays small-time scam artist Marty Jackitansky in the title role of Joel Potrykus’s second movie, released last year. On one level it’s a paean to the slacker way of life: the poster reads “He’d stand up to the man if he wasn’t too lazy to get off the f*cking couch.” Actually, Marty does get off the couch. He works a shit temp job in a bank, which enables him to order expensive office supplies with company funds so he can exchange them for cash. He closes and reopens bank accounts to collect premiums. It’s a thing of horrific beauty to watch him lying in hotel bed slurping up a plate of room-service spaghetti. What he’s doing is noble, in its way: he’s living off the leavings of the consumer economy.

When he swipes a pile of refund checks and signs them over to himself, Marty is forced to flee to the anonymity and relative safety of big bad dangerous Detroit. It’s the perfect place for a man to hit bottom and/or disappear. One of my favorite shots is when Marty scuffles along a sidewalk, a metal fence separating him from a vast platter of grass that used to be a bustling neighborhood. In the distance, the Motor City Casino shimmers in the sunshine. The shot captures the movie’s claim: the true villains here are the political and economic systems that brought Marty so low while promising, cynically and futilely, that casinos surrounded by prairies would be the salvation of a Detroit.

3. It Follows

This sleeper indie hit makes clever use of that legendary DMZ known as 8 Mile Road, the northern city limit that separates largely black Detroit from its largely white suburbs. To the north of the DMZ, a hot teenage girl named Jay (Maika Monroe) is fending off her lovelorn pal Paul (Keir Gilchrist) while pursuing hunky Hugh (Jake Weary). When Hugh takes Jay into Detroit for a Motor City staple — sex in the back seat of his car outside an abandoned factory — he chloroforms her instead of offering a post-coitus cigarette. She wakes up in her underthings, tied to a chair in an abandoned factory, while Hugh spells it out: he has just given her some kind of virus and she will be pursued by slow-moving, deadly zombies until she passes on the virus by having sex with someone else. This isn’t your garden-variety STD; this is an STP, a Sexually Transmitted Possession.

This sleeper indie hit makes clever use of that legendary DMZ known as 8 Mile Road, the northern city limit that separates largely black Detroit from its largely white suburbs. To the north of the DMZ, a hot teenage girl named Jay (Maika Monroe) is fending off her lovelorn pal Paul (Keir Gilchrist) while pursuing hunky Hugh (Jake Weary). When Hugh takes Jay into Detroit for a Motor City staple — sex in the back seat of his car outside an abandoned factory — he chloroforms her instead of offering a post-coitus cigarette. She wakes up in her underthings, tied to a chair in an abandoned factory, while Hugh spells it out: he has just given her some kind of virus and she will be pursued by slow-moving, deadly zombies until she passes on the virus by having sex with someone else. This isn’t your garden-variety STD; this is an STP, a Sexually Transmitted Possession.

It Follows taps into the familiar suburban fear of the inner city. When the kids cross 8 Mile, there are suddenly a lot of boarded-up buildings, crappy cars, and black people, plus hookers hawking their wares outside abandoned buildings. They visit the abandoned house where Hugh is squatting. But then the movie cleverly upends the old narrative by making the suburbs the truly scary side of the DMZ, with their zombies only Jay can see, their generic architecture and cars, their twinned sense of anomie and dread. When the kids flee to a remote lake house up north, it gets even worse. You can’t run away because It follows, just like all the problems that resulted when politicians and corporations eviscerated Detroit and left it for dead.

4. Lost River

Ryan Gosling’s directorial debut is uneven, to put it kindly, but it makes magnificent use of Detroit’s architecture and open spaces. Detroit stands in for the titular city, which gets its name from a reservoir that swallowed towns — a watery metaphor for what happened to Detroit. Bones (Iain De Caestecker) is one of Lost River’s holdouts, a scavenger for salable copper. As one of his last neighbors, Rat (Saoirse Ronan), packs up and gets ready to flee, he tells Bones, “I don’t wanna leave here, but I wanna live. Get out of here while you can.”

Ryan Gosling’s directorial debut is uneven, to put it kindly, but it makes magnificent use of Detroit’s architecture and open spaces. Detroit stands in for the titular city, which gets its name from a reservoir that swallowed towns — a watery metaphor for what happened to Detroit. Bones (Iain De Caestecker) is one of Lost River’s holdouts, a scavenger for salable copper. As one of his last neighbors, Rat (Saoirse Ronan), packs up and gets ready to flee, he tells Bones, “I don’t wanna leave here, but I wanna live. Get out of here while you can.”

Like the grittiest Detroiters, Bones isn’t budging. Neither is his mother, Billy (Christina Hendricks), even though she has fallen behind on a predatory mortgage loan and is in danger of losing her home to foreclosure. In desperation she takes a job at a Federico Fellini-esque burlesque house. Bones, meanwhile, is determined to find out what’s under the surface of the reservoir, which, in a nice post-apocalyptic touch, has the tops of streetlights poking through its surface.

Like the other movies on this list, Lost River is a sort of warped horror movie that uses the physical landscape of Detroit to establish a sense of abandonment and an atmosphere of menace and dread. It’s also a parable about late capitalism and globalization. What sets Lost River apart is its portrait of a family of die-hards who are determined to save their home — their city — because its theirs, and they love it, and it’s all they’ve got. Does this make them stubborn, stupid, or noble? You’ll never get an answer by looking at ruin porn. You need to go to Detroit and meet the people, the ones who stuck it out and the ones who have recently arrived. They’ll tell you the truth: there’s something in Detroit that will never die.

Or as the late great Detroit poet Philip Levine put it, Detroiters are people who endure, “since that is the only choice we have.”