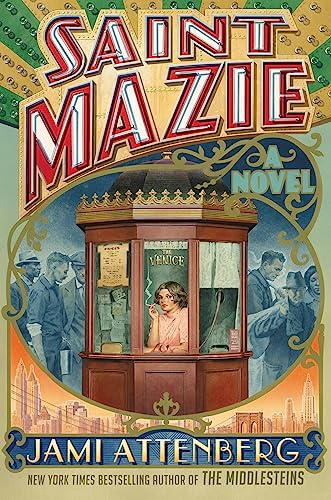

In 1940, Joseph Mitchell published a New Yorker profile of “Bowery celebrity” Mazie P. Gordon, a career ticket-taker at the Venice movie theater whose charity toward drunken bums was as legendary as it was mysterious. Seventy years later, the profile came to the attention of novelist Jami Attenberg when her friend John McCormick named his bar Saint Mazie.

“He said she was the closest thing to a saint that he’d ever heard of,” Attenberg said. “So then I became interested in her, too, and did a bunch of research on her — although there’s not actually a lot to do.”

I met Attenberg in her Williamsburg apartment, a loft with an excellent view, a minimal kitchen, and a whole lot of books. Her dog, Sid, sat at our feet for the majority of the interview, and if you follow Attenberg on any of her online platforms (Twitter, TinyLetter, Tumblr, etc.), both Attenberg and Sid are pretty much as advertised: friendly, warm, curious, and easygoing. The only time Attenberg seemed even the slightest bit taken aback was when I asked her what made her think there was a novel in Mitchell’s profile “Mazie.”

“I thought there were like 10 novels in there! I mean, she was like, friends with Chinese gangsters. That is a novel. Like, right there. All of Joseph Mitchell’s work is one massive writing prompt. He’s so good at the most precise details and leaving a little mysterious edge to everything. So I read that and it was like, complete lift-off.”

Mazie came into Attenberg’s life when she was badly in need of lift-off. She was at a low point, having been dropped by her publisher for her poor sales record. She had managed to sell a fourth novel, The Middlesteins, to a new publisher, but she couldn’t afford to live in New York. To make ends meet, she sublet her loft and traveled around the country for seven months, staying with friends and family and occasionally renting cheap apartments. She wrote about this peripatetic time for The Rumpus, describing the period as one when she “questioned everything” in her life. It was also when she wrote an early draft of Saint Mazie.

Mazie came into Attenberg’s life when she was badly in need of lift-off. She was at a low point, having been dropped by her publisher for her poor sales record. She had managed to sell a fourth novel, The Middlesteins, to a new publisher, but she couldn’t afford to live in New York. To make ends meet, she sublet her loft and traveled around the country for seven months, staying with friends and family and occasionally renting cheap apartments. She wrote about this peripatetic time for The Rumpus, describing the period as one when she “questioned everything” in her life. It was also when she wrote an early draft of Saint Mazie.

Shortly after Attenberg returned to Brooklyn to reclaim her apartment, The Middlesteins was published, and it got the kind of slow, steady, word-of-mouth attention that authors dream of. Two-and-a-half months after it was first published, it appeared on the cover of The New York Times Book Review. Before Attenberg knew it, she was a bestselling author so busy with tour dates and promotional activities that she had very little time to write — the great irony of literary success.

The Middlesteins was my first introduction to Attenberg’s writing, and like many readers, I read it because someone — actually three people — recommended it. Without knowing much about the book, I was quickly drawn into Attenberg’s portrayal of a Midwestern Jewish family trying to hold things together when the parents divorce later in life, in part because of the mother’s self-destructive over-eating. The novel’s power is in its rapidly shifting perspectives. Just when you’ve settled in with one family member, Attenberg gives you a whole new point of view to incorporate. By the end of The Middlesteins, you feel as if you’ve gotten to know a real family, that you’ve had a chance to see their flaws and love them anyway.

Attenberg says the success of The Middlesteins was like “getting a promotion,” mentioning a few factors that may have contributed to its positive reception: a better marketing campaign, snappier cover design, and smarter placement in bookstores. Ultimately, though, she thinks it was just a better book. But how do writers get better at telling stories? Attenberg has some theories. First: getting older. She wrote The Middlesteins in her late-30s, with three books to her name and some perspective on the person who wrote them.

“I think when you’re writing your debut and your first couple books, you’re working out a lot of stuff from your younger life and you have to get through all of those things. You just have to work through it. And I did that in my first three books — and a couple books that I threw away that felt like retreads.

“And I finally got to a place where I had a little perspective and could take a step back, which to me, feels like The Middlesteins. With The Middlesteins I didn’t need to write a first person book anymore. With Mazie it feels like first person, but it’s actually a multitude.”

Attenberg also began a meditation practice in her late-30s, and her practice led her to come up with a set of rules for determining future book projects.

Attenberg’s first rule is that she has to be able to express empathy and compassion within the book; the second rule is that she has to be formally inventive, (i.e. she can’t rely on the same storytelling structures over and over); and the third rule is that her writing has to be accessible.

“So, a book has to have my personal spiritual moments, a complexity or a challenge to it, and then an accessibility. So when I arrive at a story that feels that way — and I think very deeply about these things when I’m approaching something — when I feel like something is those things, then I can write that book.”

Anyone who has read Attenberg’s fiction might sense these foundational rules. There’s a depth to Attenberg’s storytelling that sneaks up on you because her sentences go down so easily. As for her formal inventiveness, it’s well on display in her new novel Saint Mazie, which is a departure from everything she’s written before. Saint Mazie is a collage of voices taken from Mazie’s diary entries, postcards, scraps of Mazie’s unpublished memoir, and interviews with people who knew Mazie. Mazie’s voice is primary, and about half the novel consists of her plainspoken, melancholy diary entries, but there are also present-day voices, interviewed by an unseen documentarian, who provide historical information and personal anecdotes about Mazie. Some early reviews have complained that these outside voices are distracting, and there were times when I agreed, but it’s clear that Mazie’s life, with all its “mysterious edges,” needed some context, and Attenberg chose a structure that provides that.

Attenberg told me that, originally, she thought that Saint Mazie would be written entirely in Mazie’s voice. In her research, Attenberg learned that Mazie had, at one point, planned to write her memoirs. Whether or not they were ever written in anyone’s guess, but Attenberg couldn’t help imagining what those pages would sound like.

“My original proposal was actually 80 pages of [Mazie’s] memoir. Which you see little bits of in the book, but they ended up taking a different form.”

Attenberg hit a wall when she realized that there was a lot of research she couldn’t do. She found herself imagining the questions she would ask of the people who had known Mazie, the reporting she would do if only her friends and family were still available for comment. Eventually she realized she could just make up the interviews and put them in the book.

“It was one of those, I woke up in the middle of the night and realized, ‘Oh, why don’t I just invent them?’ Duh.”

Saint Mazie is, above all, a character study, a reach back to the past to examine the life a woman who lived with remarkable independence, verve, and compassion — a deeply good person who had no idea that her goodness was anything unusual. In interviews for The Middlesteins, Attenberg talked about the challenge of writing about people who weren’t immediately likeable. For Mazie, the challenge was to write about someone who is, as her friend put it, “the closest thing to a saint.”

“It was almost aspirational for me, writing this book,” Jami wrote to me, via email, after our interview. “Like if I could spend time getting to know this person, maybe I could learn how to be better myself.”