James Hannaham is a busy guy. The book tour for his second novel Delicious Foods, out from Little Brown in March, has taken him to Texas, Atlanta, Phili, Richmond, and of course Brooklyn, where he lives. Not to mention his robust blog tour — interviews, essays, the whole shebang. The book has been rave-reviewed all around the mainstream literary media; it’s safe to say that this is a “breakout” moment for the 46-year-old novelist, whose first novel, God Says No, came out from McSweeney’s in 2009. It’s important to note, however, that James — whom I first met as a teaching colleague in 2011– manages to maintain an easy-going poise even as his engagement in this moment is full and intense: when I first got in touch with him about an interview, he was in between readings but in the midst of installing his first solo art show, “Lengthy Statements/Brief Statements” at Kimberly-Klark gallery in Ridgewood, Queens. (Yes, Hannaham is a visual/conceptual artist as well. He was also a founding member of the experimental theater group Elevator Repair Service). “Opportunities don’t give a shit about our schedules, do they?” he wrote. In terms of the interview, he basically said, Bring it on.

But given the volume of attention the novel has been getting, we resolved to explore questions and topics not discussed elsewhere as of yet — to make this NJAI, Not Just Another Interview. Hopefully, we’ve succeeded: at the least there is a special audio treat for readers at the end.*

What you need to know about Delicious Foods: the story centers around the eponymous evil agribusiness, a modern slave-labor operation in nowhere, La., where crack-addicted “employees,” mostly African American, are manipulated into bogus, unpayable debts (eternal servitude in exchange for drug supply). Darlene Hardison lands at Delicious Foods after her husband, a civil rights activist, is killed, and her resourceful adolescent son Eddie follows her there, eventually suffering dismemberment (he loses his hands). The rest is by turns absurd, tragic, hilarious, and sobering — the kind of novel that makes you wonder, by the end, how in the world the author managed to keep you both engaged and entertained, given the horror show of cruelty and sadness you’ve just experienced.

Is there hope at the end of this craziness? Read on…

The Millions: A much-talked-about “hook” of Delicious Foods is that alternate sections are narrated by the voice of crack cocaine personified, i.e. “Scotty.” I had the pleasure of listening to the audio version of the novel, narrated by none other than James Hannaham!

In the audio, it’s starkly apparent that something like “code-switching” is going on: third-person sections are written/read in a somewhat formal, “literary-narrator” voice, Scotty’s sections in a street voice (you’ve referred to it as “trashy”). One could argue that these are archetypal “white” and “black” voices. Were you thinking in those terms as you wrote, and/or as you read aloud?

James Hannaham: I was thinking in terms of “code switching,” yes, but I’m always thinking of code switching — it comes very naturally to me as a New York-bred person with a background in performance and a fairly good ear for the differences in speech patterns and argots of various groups. It’s something that performance of the last 25 years has been honing to perfection: I’ve admired writer/performers like Sarah Jones, Danny Hoch, Anna Deavere Smith, and Richard Maxwell’s plays for decades.

TM: Do these voices reflect a kind of prismatic sense of your own identity? Or a mocking of those identity “codes”?

JH: The voice you call “white” is a voice I actually think of as “me,” so I suppose I should take offense at that? But you know, for my entire life I’ve been taking offense at people who think that just because I can speak/write so-called “proper” English, that it suggests anything about my loyalty to black folks. Ugh. In high school, I remember nearly clocking a white girl in the face for saying that I talked “white.” A high number of my ancestors have been teachers and ministers, so to me, that voice is as black as any other “code.” I’ve appropriated it!

The technical problem of moving back and forth among several characters and narrating as Scotty was a little bit of an Olympic luge, but it allowed me to use a skill set of performer tricks that has been sort of dormant since I quit Elevator Repair Service in 2002, except for when I’ve read out loud in public.

TM: Why a formal narrative voice for Eddie’s sections, as opposed to, say, a closer third-person that sounds more like a kid?

JH: I hate it when writers approximate the language of younger children in third person just because they are the protagonists. It’s like the writer is condescending to the reader, lying about his/her actual subject position, and hog-tying him — or herself when it comes to the ability to observe astutely. It’s fiction, guys! There’s a certain amount of sleight-of-hand that goes on, and that’s not bad or forbidden. Plus, Eddie is an unusually smart kid and I wanted that to come across in the narration.

TM: You said in an interview that writing Scotty’s voice was “fun,” and that definitely shows. I was also struck by how immaculate the rhythms and syntax of the so-called dialect are — so-and-so “be doing” this and that, the use of the article “a” instead of “an,” the particular past-perfect verb construction, i.e. “had came,” “had went.” The third-person narration is “proper English,” and yet Scotty’s street syntax and grammatical constructions are perfectly crafted and consistent. Was writing that voice fluid and natural, or was there as much, or even more, crafting and revising?

JH: This strikes at the heart of my project. M.I.A. has a line in a song called “XR2” where the music stops for a second and she says, “Some people think we’re stupid / But we’re not.” I think about that a lot when I’m writing a voice like Scotty’s — I wanted the drug’s voice to hold its own against the other voices you call “white” and to do the same kinds of things, not to decide, since this was a vernacular speech pattern, that it should not display the same level of intelligence. Perhaps, I often think, it should display more intelligence, or a different kind of intelligence, or a wider variety of intelligences. The first drafts of it were relatively natural (a lot of people in my hometown speak like Scotty, truth be told) and yet I did spend a lot of time reading the voice out loud as I revised, and making sure that the voice was “consistently inconsistent” — this was a discussion I had with my editor, that the voice, since it referred so much to spoken rather than written speech, would sound more consistent if it wasn’t rigidly so, if there were a reasonable number of places where it bent the rules of its own messed-up diction.

TM: As the working conditions of the Delicious Foods farm are revealed, the reader recognizes a clear modern analog to slavery; at the same time, the narrative voice is darkly hilarious. Where on the spectrum of realism-absurdity do you see this setting and the events that occur? Hyper-real? Allegorically absurd? Satire? Parable? Metaphor? It’s fascinating, maybe a little disturbing, that in reviews I’ve seen references to all of the above. So is there a real business like Delicious Foods that you researched?

JH: Sadly, shockingly, there are many. They include:

- The case of enslavers Ronald Evans and his wife, Jequita. A lot of the details of the Evans case wound up going into the book in some fashion.

- The case of Joyce Grant, the one that initially inspired me, described by John Bowe in his book Nobodies.

- There was a six-part series by Neil Henry in the Washington Post in 1983 in which a guy who called himself “Billy Bongo” got paid to dupe a bunch of folks from DC to go all the way to the middle of North Carolina.

- And believe it or not, an actual place called Bulls-Hit Farm.

This is, of course, just one type of labor abuse among many. I’d say that, at least in the agricultural sector, the more common scheme is to traffic Mexican nationals across the border, confiscate their passports, and threaten them in order to make them pick tomatoes in Central Florida. Or the whole sex trafficking of young Eastern European and Asian women. But there are lots of disgusting variations on the theme. Take your pick.

TM: Our first introduction to Darlene is as Eddie’s crack-addicted mother, possibly responsible for her son’s having lost his hands via some gruesome violence. It’s later that we learn that she was a middle-class, college-educated woman, happily married, and involved in community organizing. Was this a kind of corrective narrative for readers who would assume certain things about female black drug addicts? Was this always Darlene’s history, or something that evolved as you got to know her?

JH: I originally thought that Darlene would be more of a person connected to the streets, maybe homeless, someone who might have a little bit more jaded of an attitude but didn’t realize how naïve she was, closer to Scotty, actually, which is how that voice wound up in the book. Then I realized that for dramatic purposes, and perhaps to suggest how much can be at stake when you end up addicted to drugs, I decided that Darlene would be a different sort of person. (You find out that she went to college very early on — Scotty says so in the first chapter.)

While it felt true to the real life experiences of people who’ve ended up victims of modern slavery, I was a little bit nonplussed to have to tell the story of a black, female, drug-addicted prostitute because of how tired and unflattering a trope it is, so I tried to do everything I could to turn that annoyingly familiar stock character on its head, from the fact that she isn’t a very good prostitute to her weird experiences to the fact that her background is not what you’d expect. Without apologizing for depicting a black female prostitute in the first place, largely because I think when a gay man (like me) writes about a female sex worker he is more likely to have something humanist and compassionate in mind, something admiring of the toughness it takes survive on the streets, rather than any vicarious titillation or essentializing misogynist bullshit.

TM: Related to this, you and I have talked a little about race and audience-awareness: for example Chris Rock’s talent for crafting jokes that somehow speak simultaneously to white people and black people, but also knowing when certain jokes are aimed for one crowd more than another. How much (if it all) in your writing process were you thinking about who would be reading these characters and their situations?

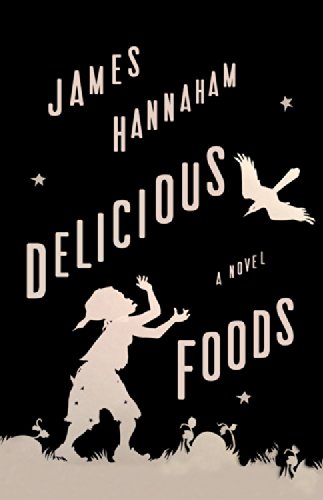

JH: I tend to think of audience in a very limited way. Not as some mass of judgy, faceless readers, but as specific friends. So I might turn a phrase and think to myself: Colleen Werthmann would find that funny. Or Ralph Lemon is going to shit himself over this. Or Tim Murphy will love that joke. In a similar spirit, the book itself is dedicated to my cousin Kara Walker (who illustrated the cover) and my bestie Clarinda Mac Low, because I think of it as a conversation starter I could get going with either or both of them. You know, “Hey Kara — have you heard about this?” “Oh my God, Clarinda, you aren’t going to believe what I just read about.” I like to presume that I live in a world where the humanity of black people is not an open question but a foregone conclusion (thank you, Toni Morrison!), and so I try to write without any self-consciousness about human beings and their problems (facing racial discrimination being one) rather than worrying about who will approve or disapprove. What was the slogan from that Harlem Renaissance magazine FIRE!!!?

If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow; strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

Langston Hughes said that. Or, as Fishbone used to chant during their raucous live shows in the 80s, “Fuck y’all / If y’all don’t like it / Fuck y’all / If y’all don’t like it.”

TM: And looping back to the question about allegory versus reality, what are you hoping readers walk away with in terms of socio-political-racial awareness? (On one hand, this can be a deductive question to ask an artist about his creative work, and yet your book party was a benefit for Free the Slaves, a nonprofit organization that battles human trafficking, so it seems perhaps a fair question?) And do you have different hopes for black readers and non-black readers?

JH: I’m not really as interested in the reader’s take-away, per se, as I am in putting a metaphorical defibrillator up against their received ideas about discrimination even more than race. Depicting racial discrimination is just a way of starting a conversation about a power relationship or power food chain, really, that is hardly exclusive to black Americans and white Americans, despite how much we love to privilege it and pretend that no other struggle matters. Even poor white Americans need to be aware that they’re someone’s niggers, too, right? Almost everybody’s likely to be someone’s nigger. Didn’t Yoko Ono sing, “Woman is the Nigger of the World” in 1972?

TM: I am wondering how the writing, and the reception, of the novel have affected your own sense of hope/optimism in relation to race and injustice. One reviewer seemed keen to see the novel’s ending as hopeful:

From what we’ve seen go down at Delicious, from the tenacity of this mother and son, we know it’s love that keeps us going. Love is a rock every bit as hard as those diamond stars. Its indestructible beauty is enough to break down the earthly rocks that are its meager imitations.

I confess that I read the book ultimately more darkly than that: the final pages evoke sheer survival as primary — God, myth, and family all prove paltry. Even art is somewhat disempowered (“All stories betray you”). And let’s not forget that Eddie has no hands. What say you about hope?

JH: I’m more on your side, frankly. I long ago adopted a happy sort of pessimism as a lifestyle choice, since I always found it best to be prepared for the worst and pleasantly surprised if things turned out great. Your reading of the ending is closer to what I’m suggesting, that love — even the love of one’s family — pales in comparison to the instinctual desire to survive; my suspicion is that the desire to survive, for those who haven’t lost it, is jammed into our brain stem or something, connecting us to our true animal nature. In most of the narratives of long-term hardship that I’ve read or seen (I was a big fan of a show called I Shouldn’t Be Alive), everything else tends to fall away after a certain desperate moment. You want to live simply because you want to live.

I am also thinking of the end of that documentary film Hands on a Hardbody, in which the person who triumphs is not the religious fanatic with her entire congregation praying for her to win the pickup truck, but a deer stander who quietly endures with unfathomable (and entirely secular) patience. As for my hopes about discrimination and injustice, I’ll offer two quotes. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” says Martin Luther King. More recently, Kara Walker replies, in the title of a controversial drawing featuring a tiny Barack Obama trying to lecture at a podium while surrounded by what looks like an insane race riot, “The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos.” All I’ll say is, I’m her first cousin, not his.

I am also thinking of the end of that documentary film Hands on a Hardbody, in which the person who triumphs is not the religious fanatic with her entire congregation praying for her to win the pickup truck, but a deer stander who quietly endures with unfathomable (and entirely secular) patience. As for my hopes about discrimination and injustice, I’ll offer two quotes. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” says Martin Luther King. More recently, Kara Walker replies, in the title of a controversial drawing featuring a tiny Barack Obama trying to lecture at a podium while surrounded by what looks like an insane race riot, “The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos.” All I’ll say is, I’m her first cousin, not his.

TM: In an interview you did with Bookslut about your first novel God Says No back in 2009, you revealed that you were 40 years old; the interviewer asked “What was the holdup?” and I loved your answer (because later-life blooming is my thing):

TM: In an interview you did with Bookslut about your first novel God Says No back in 2009, you revealed that you were 40 years old; the interviewer asked “What was the holdup?” and I loved your answer (because later-life blooming is my thing):

“What was the holdup? I didn’t learn to read until 1990. What the fuck do you mean what was the holdup? Actually…somebody once told me that the average age for the publication of a first novel is 49. I don’t know if it’s true, but I love that statistic.”

Can you talk about how God Says No — a tragicomic novel about identity, i.e. a black, Christian, gay man muddling through identity crisis, double-life, self-acceptance — is both a “typical first novel” and, perhaps because you were older and more evolved as a person, a subversion of the typical first novel?

JH: I don’t think I would’ve written a typical first novel even if I’d been 23 at the time. Even then, people already expected me to do weird-ass, arty things like joining a performance group. I meant for GSN to seem like a typical first novel because of the material that inspired me: clunky firsthand testimonials including magical events that happen to closeted people. I felt as if people would assume a lot of literal connections between myself and Gary, the protagonist, but that I’d set a kind of trap by doing so, a trap designed to free people from the assumption that the typical first novel is always a thinly veiled autobiography; and that if I could do so seamlessly, I would have achieved something interesting. People still think I’m from Florida because of that book, which makes me quietly proud of it. And there are things I have in common with Gary, but not many.

TM: So tell us about the über-Renaissance man thing — actor/performer, visual artist, novelist. How do all these parts of your brain and life work together? Or is there a sequential trajectory to this, i.e. are you becoming “primarily” a novelist, less so a performer or visual artist?

JH: There’s a fine line between “Renaissance man” and “dilettante,” I guess: perhaps the aura of success makes the entire difference? People seem oddly interested in making me choose one “thing” despite the many ways in which these “genres” affect one another in my head, whereas I’m perfectly comfortable trying, at least, to consider them all one thing. “Is not all one?” asks the Buddhist koan.

I suppose it’s funny that I left Elevator Repair Service right at the moment when they started staging novels, though I’m not sure that it means anything for me or for them other than an odd coincidence. There are aspects of performance that still affect the way I write, and while I like performing, I was never any good at memorizing, so the aspects of putting a book out that have to do with performance without memorization (doing public readings, reading the audiobook) are kind of perfect for my “skill set,” as the Millennials might put it.

TM: I’m always just slightly ambivalent when I see a deserving artist’s fringe-ness become “discovered.” On the one hand, it’s absolutely great — for the artist, and also for the world. But it’s also a little like neighborhoods gentrifying a little too much, or Bon Iver winning the Grammy in 2012 and being like, I’ve always thought this award stuff is kind of bullshit, and I don’t know what to do with the fact that I’m here. Is it fair to say you’ve mostly worked and lived in the realms of subversion and alternativeness up until now? And so in going from indie press to big publisher, for example, and with mainstream attention coming to Delicious Foods, do you feel that transition happening for you? Or is this just not something you think/care about?

JH: I wouldn’t have guessed that this book would be the breakthrough, that’s for sure. I mean, more than GSN is the typical first novel, I thought Delicious Foods was the dark, ambitious, difficult, less compromised, and strange second novel, a.k.a., the flop, the “cult favorite, ” if it gets that lucky. So I am a little nonplussed. But it’s encouraging.

I guess I don’t really think of myself as “having worked and lived in the realms of subversion and alternativeness” (which you make sound so spooky) since so much of my contact with institutions has been so normal: I went to Yale and the University of Texas, for Pete’s sake. I taught at Columbia. I only have one tattoo and my piercing sealed itself up. I’m built like a meathead linebacker. Could I seem less subversive? But maybe those institutional associations have provided a smokescreen for my true black gay freakiness. It’s just that I don’t think of my true black gay freakiness as subversive, any more than the true white straight Republican freakazoids out in the heartland think of themselves as subversive, even as they’re plotting to replace the government with a bunch of gender normative marionettes and privatize motherhood or whatever. Perhaps that makes it a kind of entitled black gay freakiness. I certainly don’t mind modeling that for whoever wants it.

*Click here to listen to a clip from James Hannaham’s audio recording of Delicious Foods.