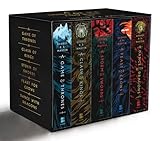

All readers have seen literary works they adore adapted for the screen, cataloging, scoffing, cringing, and wondering at changes to the original narrative — or, if lucky, delighting in them. No readers, though, have had the experience that devotees of A Game of Thrones, or more specifically, of George R.R. Martin’s in-progress suite of novels A Song of Ice and Fire, are about to. The upcoming season of HBO’s Game of Thrones will reportedly push past Martin’s fifth and most recent book, extending numerous plotlines beyond where readers last left their heroes. The series will continue to do so until it concludes, presumably reaching its denouement long before Martin can publish the two remaining novels he plans.

Fansites are abuzz with virtual hand-wringing about this, their anxiety different from the usual panic about a screen version’s faithfulness. Game of Thrones is about to go where no adaptation has gone before, into the realm of the unpublished source, adapting books that do not yet exist, that will become available later — thus undercutting the very premise of adaptation. Anyone fatigued with Game of Thrones, the socio-technological phenomenon — most illegal downloads! most on-line videos of viewers watching characters die! — may find their interest piqued by the show’s challenge to modern assumptions about adaptation and the idea of canon.

Fansites are abuzz with virtual hand-wringing about this, their anxiety different from the usual panic about a screen version’s faithfulness. Game of Thrones is about to go where no adaptation has gone before, into the realm of the unpublished source, adapting books that do not yet exist, that will become available later — thus undercutting the very premise of adaptation. Anyone fatigued with Game of Thrones, the socio-technological phenomenon — most illegal downloads! most on-line videos of viewers watching characters die! — may find their interest piqued by the show’s challenge to modern assumptions about adaptation and the idea of canon.

Our notions of original and adaptation logically privilege chronology. We call the first published version of a narrative the original and consider the versions that follow adaptations — less definitive, and somewhat degraded. We make exceptions, of course: William Shakespeare’s plays are adaptations, but their stature is elevated by his genius and cultural context. (For Shakespeare’s time, indeed, notions of originality and adaptation would have made no sense.) We are also used to privileging print above screen, but chronology seems to takes precedence: nobody gives a darn that Graham Greene’s screenplay and subsequent novella of The Third Man call (absurdly) for the hero to get the girl at the end, because nobody saw his screenplay before the film came out; the novella also arrived afterwards.

Our notions of original and adaptation logically privilege chronology. We call the first published version of a narrative the original and consider the versions that follow adaptations — less definitive, and somewhat degraded. We make exceptions, of course: William Shakespeare’s plays are adaptations, but their stature is elevated by his genius and cultural context. (For Shakespeare’s time, indeed, notions of originality and adaptation would have made no sense.) We are also used to privileging print above screen, but chronology seems to takes precedence: nobody gives a darn that Graham Greene’s screenplay and subsequent novella of The Third Man call (absurdly) for the hero to get the girl at the end, because nobody saw his screenplay before the film came out; the novella also arrived afterwards.

These principles lurking in our thoughts, we usually watch screen adaptations of our favorite books with a kind of dual consciousness, what adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon calls (with a nod to Mikhail Bakhtin) “an ongoing dialogical process,” and “an intertextual pleasure that…some call elitist and others enriching.” That is, we watch adaptations and enjoy comparing them to the source, perhaps thinking That’s not what happens in the book or I caught that in-joke. The adaptations I have in mind here are neither the inspired by kind, nor the let’s focus on two minor characters instead of Hamlet kind. Productions like Game of Thrones are predicated on a large degree of faithfulness. Sure, the series has deviated and bastardized — every season moves further afield of the books — but it does so largely in order to keep protagonists in the foreground and Martin’s structure intact.

Until now. The producers, to whom Martin has revealed his plans for the conclusion of his books, have announced that henceforth the adaptation will diverge significantly. Naturally, they have not announced how much, or starting when, or with which plotlines and character arcs, and that’s where this gets interesting. Devoted readers’ “intertextual pleasure” will be tempered with uncertainty, as they may find themselves thinking: That’s not what happens in the books — yet! or I don’t know any more about this than my idiot friend here does. The commentariat has expressed concern about spoilers for the books, but the fact is, no one will know when the show is revealing Martin’s plot and when it is telling a different story. As a corollary, when readers finally receive Martin’s sixth and seventh novels, they may be discomfited by literary narratives contradicting the screen version.

This reversed chronology of print to screen destabilizes categories of original and adaptation. Yes, the next three seasons of Game of Thrones will still spring from Martin’s fictional world, but when the series becomes first to portray developments beyond the books’ chronology, when its narrative unfolds in dialogue not with a prior text but only with fan speculation, labeling it an adaptation will seem wrong. What if Martin revises his plot under the influence of the show? (Will anyone know that he has not?) Which then becomes original, and which adaptation? The conceptual binary is inadequate.

Similarly disrupted by the particularities of Game of Thrones is the notion of canon, the designation of certain texts as authentic at the expense of others. The term dates to the early Christians, who felt the need to legitimate the real gospel created by the right people under divine guidance, as opposed to apocryphal spin-offs. Our current idea of canonicity derives from this sense of a unified and godlike authority. Its 20th-century paradigm is perhaps the case of Sherlock Holmes: when Arthur Conan Doyle, tired of churning out detective stories, killed off the beloved sleuth in 1893, readers filled the void with fan fiction and biographies, even after Conan Doyle bowed to pressure and resuscitated — and copyrighted — the character in 1903. The preponderance of Sherlockiana was termed non-canonical by the literary industry, despite much fan dissent. It is an example that highlights canonicity’s deference to the powers of the creator, authorial intention combined with intellectual property law and the marketplace.

In recent years, the deployment of canonicity has resurged as technology has exponentially expanded the dissemination of texts. It is especially present in the context of science-fiction and fantasy, genres that are set in fictional realms, worlds subsequently used in adaptations and continuations, whether licensed (such as recent novels depicting Isaac Aasimov’s Foundation world, or commercial video games, role-playing games, etc., based on film and book franchises) or unlicensed (fan fiction, costumed play). The idea of canon helps those who care maintain clear divisions between what really happened in that universe, according to its creator(s), and what is some loser’s version of what could have happened. Of course, there are disturbances in the force: the Star Wars films re-edited and revised by creator George Lucas in the 1990s have been anointed by their creator as canon. But so many enthusiasts publicly denounce Lucas’s rewriting of specific moments — such as when Han Solo is fired upon by Greedo first, and only then shoots back — that the significance of canon diminishes. Lucas’s reaction has been to make the revisions the only versions commercially available and claim that the original reels are ruined. The canon, it turns out, is auteur theory beholden to intellectual property rights and to estates covering their assets, but may be challenged by audiences voting with their mouse-clicks and wallets.

In recent years, the deployment of canonicity has resurged as technology has exponentially expanded the dissemination of texts. It is especially present in the context of science-fiction and fantasy, genres that are set in fictional realms, worlds subsequently used in adaptations and continuations, whether licensed (such as recent novels depicting Isaac Aasimov’s Foundation world, or commercial video games, role-playing games, etc., based on film and book franchises) or unlicensed (fan fiction, costumed play). The idea of canon helps those who care maintain clear divisions between what really happened in that universe, according to its creator(s), and what is some loser’s version of what could have happened. Of course, there are disturbances in the force: the Star Wars films re-edited and revised by creator George Lucas in the 1990s have been anointed by their creator as canon. But so many enthusiasts publicly denounce Lucas’s rewriting of specific moments — such as when Han Solo is fired upon by Greedo first, and only then shoots back — that the significance of canon diminishes. Lucas’s reaction has been to make the revisions the only versions commercially available and claim that the original reels are ruined. The canon, it turns out, is auteur theory beholden to intellectual property rights and to estates covering their assets, but may be challenged by audiences voting with their mouse-clicks and wallets.

Game of Thrones makes all this clearer, even as it offers the possibility of a less monolithic sense of canon. It may be, years from now, that the novels will be seen as canon, that audiences will instinctively defer to Martin’s vision. But Martin himself, by inviting the show creators to deviate from his plot, has opened up the possibility that two versions can exist on equal terms. Then, as now, more people will have seen the series, and seen it first, than will have read the books. Someday it may be considered as canonical as the second of the two Adam and Eve stories in the Old Testament.