1.

Count weather among the forces that I move through life without fully understanding. On a recent frigid Saturday, a sharp chill hunted my joints through worn thermals and cheap gloves. Forget grocery shopping, not with the stroller, not in this cold. My 16-month-old son and I retreated to the library. More than basmati rice or cauliflower, we needed open space, the familiar thick carpet where he could squat and squeal freely. We needed the warm light of enormous lampshades embossed with ants, birds, and humpback whales. We needed more books.

Maybe that should read “wanted.” My son hadn’t tired of Good Dog, Carl or My Friends. He’d started requesting Tickle, Tickle by name. His mother invoked Knuffle Bunny while he handed her laundry, and Brush Your Teeth, Please had helped me transform a grim chore into something like dessert. (Grape-flavored toothpaste deserves some credit here). For weeks, maybe months, books had reliably engaged him, exciting or calming him depending on the title, the time of day, and what could be called his nascent taste. A rotation of Goodnight, Moon, Good Night, Gorilla, and Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site guided him to sleep most nights. Our afternoons sometimes focused on books of a certain theme: bunnies, oceans, dogs, primates. Reading was becoming a force that shaped his world, but unlike a polar vortex or a hurricane, it felt like a force within parental control. Three weeks later, our borrowed books due, I am less sure. I can control the presence or absence of books. I can curate his library. I can open the book and ask him “Where is the bird?” After that, mystery follows. Once the words leave my mouth for his ears and brain, they enter a universe where nothing is fixed.

Maybe that should read “wanted.” My son hadn’t tired of Good Dog, Carl or My Friends. He’d started requesting Tickle, Tickle by name. His mother invoked Knuffle Bunny while he handed her laundry, and Brush Your Teeth, Please had helped me transform a grim chore into something like dessert. (Grape-flavored toothpaste deserves some credit here). For weeks, maybe months, books had reliably engaged him, exciting or calming him depending on the title, the time of day, and what could be called his nascent taste. A rotation of Goodnight, Moon, Good Night, Gorilla, and Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site guided him to sleep most nights. Our afternoons sometimes focused on books of a certain theme: bunnies, oceans, dogs, primates. Reading was becoming a force that shaped his world, but unlike a polar vortex or a hurricane, it felt like a force within parental control. Three weeks later, our borrowed books due, I am less sure. I can control the presence or absence of books. I can curate his library. I can open the book and ask him “Where is the bird?” After that, mystery follows. Once the words leave my mouth for his ears and brain, they enter a universe where nothing is fixed.

This particular trip to the library marked the end of an eventful week in his early literacy. At bedtime the previous Sunday, he had restacked his books to recover a strategically buried title, Trains Go. My son sat in his typical way, circling once and bracing with both hands before thudding down. (“I learned to sit from my friend the dog…”) He laughed, looking like a tiny John Belushi. In this moment, I saw a flash of what I’ve heard other parents call the Boy-Boy, a term I understand but dislike. He raised the book, which we had read dozens of times, above his head.

In that moment I thought about another force in the world, the force behind the very idea of a Boy-Boy: I thought about gender. My son leaned forward, arms raised and extended. A smile strained his cheeks, seven tiny teeth bared. His whole body twisted into an absurd, miniature shrine to the ultimate Boy-Boy book, which he loves with an intensity that surprises me, though I bought it for him. How little control I have over what gender information he learns! Male adults he has barely met teach him “High five!” and call him “Buddy.” His favorite YouTube videos feature John Lee Hooker wanly performing “Boom, Boom, Boom,” and Ray Charles teaching The Blues Brothers to “Shake a Tail Feather.” The two-year-old boy at the Houston Children’s Museum shows him that cars go “rrrrrr,” and by that evening, my son imitates him precisely. At a playground’s toy house, a trio of four-year-old girls cold shoulders him; at daycare, where his favorite place to play is the toy kitchen, his three tias teach him that la cocina is for boys, too. This thrills his mother and me, even if we still haven’t been able to stop calling him, affectionately, “Mister, Mister.” That night, my son held Trains Go over his head and I thought, Gender is weather: it’s a force you can’t do much to change, the changes of which are are over time unpredictable and not entirely benign.

In that moment I thought about another force in the world, the force behind the very idea of a Boy-Boy: I thought about gender. My son leaned forward, arms raised and extended. A smile strained his cheeks, seven tiny teeth bared. His whole body twisted into an absurd, miniature shrine to the ultimate Boy-Boy book, which he loves with an intensity that surprises me, though I bought it for him. How little control I have over what gender information he learns! Male adults he has barely met teach him “High five!” and call him “Buddy.” His favorite YouTube videos feature John Lee Hooker wanly performing “Boom, Boom, Boom,” and Ray Charles teaching The Blues Brothers to “Shake a Tail Feather.” The two-year-old boy at the Houston Children’s Museum shows him that cars go “rrrrrr,” and by that evening, my son imitates him precisely. At a playground’s toy house, a trio of four-year-old girls cold shoulders him; at daycare, where his favorite place to play is the toy kitchen, his three tias teach him that la cocina is for boys, too. This thrills his mother and me, even if we still haven’t been able to stop calling him, affectionately, “Mister, Mister.” That night, my son held Trains Go over his head and I thought, Gender is weather: it’s a force you can’t do much to change, the changes of which are are over time unpredictable and not entirely benign.

The horizontal outline of Trains Go settled in my hands, and the contours of its worn cardboard pages dragged me out of abstraction. “Junebug, we read that already,” I said. He grunted, then opened it in his own lap. “Wooo woooo wooooooo,” he said, reading words not on that page, but the next one. I shook my head, astonished. The next storytime, he opened The House in the Night, flapping his lips and saying “bah-bah, baah-baaah,” as he must think I do. He learns, as toddlers do, through mimicry. On the shelf above Harold and the Purple Crayon and the one below What to Expect: The Second Year rests my neglected copy of Poetics, in which Aristotle says: “Imitation is natural to man from childhood, one of his advantages over the lower animals being this, that he is the most imitative creature in the world, and learns at first by imitation.” Reading this, after he went to bed that night, I wondered even more intensely, what does he learn about gender from me? Does he learn the next claim in Poetics, that “it is also natural for all to delight in works of imitation.” All feels impossible, because I know I cannot delight in the countless imitations of violence and chauvinism and privilege I witness in too many fathers and sons and brothers and husbands. So if I can’t delight, can he? Of course he can. I start to worry that I should be more vigilant in my observations. What exactly does he imitate? What does he ignore?

The horizontal outline of Trains Go settled in my hands, and the contours of its worn cardboard pages dragged me out of abstraction. “Junebug, we read that already,” I said. He grunted, then opened it in his own lap. “Wooo woooo wooooooo,” he said, reading words not on that page, but the next one. I shook my head, astonished. The next storytime, he opened The House in the Night, flapping his lips and saying “bah-bah, baah-baaah,” as he must think I do. He learns, as toddlers do, through mimicry. On the shelf above Harold and the Purple Crayon and the one below What to Expect: The Second Year rests my neglected copy of Poetics, in which Aristotle says: “Imitation is natural to man from childhood, one of his advantages over the lower animals being this, that he is the most imitative creature in the world, and learns at first by imitation.” Reading this, after he went to bed that night, I wondered even more intensely, what does he learn about gender from me? Does he learn the next claim in Poetics, that “it is also natural for all to delight in works of imitation.” All feels impossible, because I know I cannot delight in the countless imitations of violence and chauvinism and privilege I witness in too many fathers and sons and brothers and husbands. So if I can’t delight, can he? Of course he can. I start to worry that I should be more vigilant in my observations. What exactly does he imitate? What does he ignore?

2.

I am probably more typically masculine now, as a father and husband, than I have been since age seven, when I left behind construction trucks and dinosaurs for a Cabbage Patch doll in a Boston Red Sox uniform. I named the doll Ellis Burks, after the actual center fielder, and I thought I treated him with the tenderness any of the Girl-Girls in the playhouse. I referred to him formally, using only his complete name. Ellis Burks, drink your milk. Ellis Burks, go to sleep. Ellis Burks, why are you crying? Ellis Burks, let’s play catch.

Later in elementary school, after I memorized the presidents in order using flashcards my father had bought me, my cousins and I filled summers with games of “White House” on piles of seaside driftwood. “White House” cribbed its structure from your typical “House” played by aspiring princesses everywhere. I adapted it, persuading my younger siblings and cousins to assume the identities of actual figures: Aaron Burr, my shifty vice president, James Madison, my trusted secretary of state. My cousin Kate, of course, was Mrs. Jefferson. As a parent, my younger self’s lack of imagination for the female roles troubles me. Nerd that I was, fidelity to fact did not keep me from asking Kate’s older sister to play Queen Victoria (not yet crowned) or Catherine the Great (dead). No: a hole in my own concept of the world, a lack of schema for powerful women in that world, is what kept my sister from playing Sacajawea, reporting back with Lewis and Clark, her twin boy cousins. I hadn’t learned to expect to see women in the White House as anything other than first ladies, despite having read through countless books providing stories of men to populate a constructed world. I’d read these books, of course, at the place I had taken my son on that freezing Saturday — my local library.

Leaving the library, I pushed my son north on St. Nicholas Avenue. My voice described what we passed — “There’s a streetlamp, and a WALK signal. This street is 1-7-9, which is one more than 1-7-8 and one less than 1-8-0. Look there’s a yellow light, it means slow down. That car has its hazards on, those lights are for parking illegally.” My mind sorted through the way each incident in his young life left a trace of information, a tiny dot. Even in its flawed form, “White House” was only possible because I’d connected dots between texts. A few days before he read Trains Go to me, I had noticed my son apparently doing the same thing. Sorting his library before bedtime, he double-fisted Sandra Boynton books, opening The Going to Bed Book, then Opposites. Like most Boynton books, these two shared an ensemble of cartoonish animals: a moose, a hippopotamus, a rabbit, a cat. He opened both books and compared them, turning a page in one, then looking at the other, turning a page in that one, then looking at the first book. This moment returned to me on the cold walk home, and I did a quick census. Only the hippopotamus had a clearly stated gender. This is a problem, I thought.

Leaving the library, I pushed my son north on St. Nicholas Avenue. My voice described what we passed — “There’s a streetlamp, and a WALK signal. This street is 1-7-9, which is one more than 1-7-8 and one less than 1-8-0. Look there’s a yellow light, it means slow down. That car has its hazards on, those lights are for parking illegally.” My mind sorted through the way each incident in his young life left a trace of information, a tiny dot. Even in its flawed form, “White House” was only possible because I’d connected dots between texts. A few days before he read Trains Go to me, I had noticed my son apparently doing the same thing. Sorting his library before bedtime, he double-fisted Sandra Boynton books, opening The Going to Bed Book, then Opposites. Like most Boynton books, these two shared an ensemble of cartoonish animals: a moose, a hippopotamus, a rabbit, a cat. He opened both books and compared them, turning a page in one, then looking at the other, turning a page in that one, then looking at the first book. This moment returned to me on the cold walk home, and I did a quick census. Only the hippopotamus had a clearly stated gender. This is a problem, I thought.

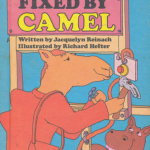

It could only be fixed by camel.

“Fixed by Camel,” was a phrase my father, a one-time carpenter, had used after reassembling my son’s crib in our new apartment. At Christmas, to clarify, he gave my son Jacquelyn Reinach’s Sweet Pickles book Fixed by Camel, a gift as much for me — and for him — as it was for my son. With the book in my hands, I immediately remembered Clever Camel and her brick-orange, long-sleeved coverall jumpsuit. How she outsmarts Kidding Kangaroo when he strands her on a roof, traps her under a manhole cover, and defaces the park benches she paints. How she captures him in a jungle gym snare, lured by an irresistible sign reading “DANGER DO NOT RING DOORBELL UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.” How she also leaves a glass of milk and two peanut butter sandwiches, which she tells him he should eat while he waits for her sidewalk to dry. I always loved that Camel — calm, solutions-oriented, quick-witted, and compassionate — was female. The writer’s choice to explicitly gender her felt radical to me, risky, rare. It added depth and surprise, two qualities Aimee Bender calls universal pleasures in a close read of her infant twins’ favorite book, Good Night, Moon.

“Fixed by Camel,” was a phrase my father, a one-time carpenter, had used after reassembling my son’s crib in our new apartment. At Christmas, to clarify, he gave my son Jacquelyn Reinach’s Sweet Pickles book Fixed by Camel, a gift as much for me — and for him — as it was for my son. With the book in my hands, I immediately remembered Clever Camel and her brick-orange, long-sleeved coverall jumpsuit. How she outsmarts Kidding Kangaroo when he strands her on a roof, traps her under a manhole cover, and defaces the park benches she paints. How she captures him in a jungle gym snare, lured by an irresistible sign reading “DANGER DO NOT RING DOORBELL UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.” How she also leaves a glass of milk and two peanut butter sandwiches, which she tells him he should eat while he waits for her sidewalk to dry. I always loved that Camel — calm, solutions-oriented, quick-witted, and compassionate — was female. The writer’s choice to explicitly gender her felt radical to me, risky, rare. It added depth and surprise, two qualities Aimee Bender calls universal pleasures in a close read of her infant twins’ favorite book, Good Night, Moon.

After our trip to the library, I sat down with my son and Fixed by Camel. As with A is for Activist and A Rule is to Break: The Child’s Guide to Anarchy, as with Ganesha’s Sweet Tooth and Press Here, the first read felt more for my pleasure than for his. Clever Camel might have been a revelation for me as a child, a fixed point from which I could explore the idea — gender — that I still don’t understand. But my guidepost can’t be my son’s. He’ll find his own, in time, and I can hope that he does that because I help him ask better questions, no matter what those questions, or their answers, might be. This thought chased my disappointment with his reaction to the book. There’s nothing broken, nothing to be fixed. Aristotle didn’t have the last word on imitation; the modernists and phenomenologists saw to that. “Of course, works of art imitate the objects they represent, but their end is certainly not to represent them,” Jacques Lacan once wrote. “In offering the imitation of an object, they make something different out of that object. Thus they only pretend to imitate.” Whether or not my son’s imitations of men and what they should love are pretend, they are his attempts to be in the world and to love it. Every time he surprises me with that sort of expression, I need to be grateful beyond words. Imposing my version of gender, my preference for skepticism and nonconformity, isn’t any more appropriate or healthy than forcing him into army fatigue onesies or calling him “Daddy’s Big Guy.” Yes, I hope to expose him to stated versions of all kinds of gender, not only your Gymboree binary, not only Boynton’s sexless bestiary. Yes, I plan to fight the tendency to make the default gender male. But most of all, I think of the gift my father gave to his son when he gave Fixed by Camel to mine. The book transmitted of a spark, bequeathing to my son and I both an encounter with surprise and depth. It’s that electricity I want to conduct. My father’s easy transfer of precise kindness is something I may well spend my life learning to imitate.

After our trip to the library, I sat down with my son and Fixed by Camel. As with A is for Activist and A Rule is to Break: The Child’s Guide to Anarchy, as with Ganesha’s Sweet Tooth and Press Here, the first read felt more for my pleasure than for his. Clever Camel might have been a revelation for me as a child, a fixed point from which I could explore the idea — gender — that I still don’t understand. But my guidepost can’t be my son’s. He’ll find his own, in time, and I can hope that he does that because I help him ask better questions, no matter what those questions, or their answers, might be. This thought chased my disappointment with his reaction to the book. There’s nothing broken, nothing to be fixed. Aristotle didn’t have the last word on imitation; the modernists and phenomenologists saw to that. “Of course, works of art imitate the objects they represent, but their end is certainly not to represent them,” Jacques Lacan once wrote. “In offering the imitation of an object, they make something different out of that object. Thus they only pretend to imitate.” Whether or not my son’s imitations of men and what they should love are pretend, they are his attempts to be in the world and to love it. Every time he surprises me with that sort of expression, I need to be grateful beyond words. Imposing my version of gender, my preference for skepticism and nonconformity, isn’t any more appropriate or healthy than forcing him into army fatigue onesies or calling him “Daddy’s Big Guy.” Yes, I hope to expose him to stated versions of all kinds of gender, not only your Gymboree binary, not only Boynton’s sexless bestiary. Yes, I plan to fight the tendency to make the default gender male. But most of all, I think of the gift my father gave to his son when he gave Fixed by Camel to mine. The book transmitted of a spark, bequeathing to my son and I both an encounter with surprise and depth. It’s that electricity I want to conduct. My father’s easy transfer of precise kindness is something I may well spend my life learning to imitate.

Image Credit: Pixabay.