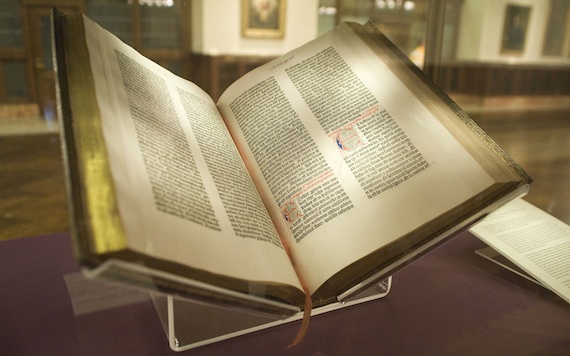

The Gutenberg Bible is a book of extraordinary beauty. One might even say it exudes beauty: its gleaming hand-tooled leather cover beckons to the hands to touch, to open, to reveal what lies inside. The day I saw it, it was sitting on the library table like a fat monarch laid in state, a foot wide by nearly a foot and a half long, light reflecting off the metal cornerpieces a binder had affixed for its protection half a millennium before. I asked Paul Needham, the librarian at Princeton’s Scheide Library, if I should put on gloves. He shook his head. Linen rag is not disturbed by finger oils, while calfskin in fact thanks them. I raised the solid wood-and-leather board. It opened right onto the text: two perfect jet-black columns, the ink still glossy after all this time. I turned one massive page, and then the next, intoxicated by the touch, the smell, the grace of that black block against the broad and creamy margins. To my amazement, I was leafing through the most famous and valuable book in the world, the first major volume made with metal type — the Ur-book of the age of print. Yet beyond all these superlatives, it was simply beautiful.

This volume, one of 48 that survive, was crafted with exquisite care roughly 560 years ago. Its makers — one inventor, one scribe, and one merchant who dealt in books — chose for each page the crispest letterforms, the purest linen, the ideal proportions of the golden section. In short, they selected the finest possible form to clothe the most sacred text of their age, the Christian Scriptures. I studied this book for several years, and have come to think that it has much to tell our age as well. For this Biblia latina, more than any other book, makes one thing clear: the more we value a text, the more we desire to fix it in the world, to grant it permanence. Today, as we rush headlong into the digital age, it seems to me that a similar tendency can be discerned. For against all expectation, we readers maintain our stubborn attachment to physical books, as though what they contained were somehow sacred.

By now most of us are heartily sick of the print versus e-book debate. It was framed wrong from the start: as a Manichean proposition, one or the other, either-or. Fortunately, we have our own experience now to instruct us — as well as the long history of the book. The evolution of reading technologies is both “broken and continuous,” in the words of the book historian John Pettegree; each successive form coexists with the one it replaces for some time. Most of us read some things on screen, other things in print; seven years after the invention of the Kindle, readers are answering this question for themselves. We need only look back to the first age of print to see that this is how technologies evolve. The hand copying of manuscripts by scribes did not vanish in 1454, when Johann Gutenberg and his colleagues unveiled the new system of printing with movable type. Nor did it die out completely when Aldus Manutius invented the killer app for print in 1500 in Venice, the handheld personal book — nor even in 1517, when Martin Luther’s 95 printed theses sounded the death knell for clerical rule. Hand copying persisted well into the 16th century, for special texts desired by wealthy rulers and clergy. Even today, fine letterpress printing and calligraphy are used for luxury editions of the classics for a similar clientele. For a time, and for a particular purpose, old technology persists. Where then, in 2015, do we stand with the printed book?

Beneath the barrage of e-hype, it turns out that the humble codex — the Latin term for books with spines and leaves — is holding its own. The statistics can appear confounding, but essentially the market is settling out. It is true that overall book sales have been dropping for some time. The American market saw a drop from 770 million copies sold in 2009 to 635 million in 2014 (the figures were 229 million and 181 million for the U.K.) according to Jonathan Nowell, president of Nielsen Book, the main industry tracker. Given all the other ways we spend our leisure time today, that’s not surprising. More tellingly, the rate of e-book buying has leveled off after years of explosive growth. E-books now comprise less than a third of all books sold. The first flush of digital adoption has passed, it seems; hardcover sales (particularly for picture books and adult nonfiction) have held up well, Nowell told the Digital Book World conference in January. It is paperbacks that have been cannibalized by e-books. This picture will naturally shift as we move ever forward into new digital experiences. But I find it remarkable that at a time of massive digital immersion, a majority still prefers to consume their reading the old-fashioned way.

The physical places where such books are bought aren’t dying either. The independent brick-and-mortar bookshop is slowly reviving in America, with glimmers of a similar rebound in Britain. The numbers are nowhere near what they were before the big chains and Amazon, but last year more new bookstores opened in the United States than in any year since the 2008 recession, the American Booksellers Association reported (for the record, 59). Sales of physical books at Britain’s leading chain, Waterstone’s, rose five percent in December, and the British Library’s chairman, Rory Keating, recently took a stab at explaining why visitor figures rose 10 percent in 2014. It’s not just the free Wi-Fi, apparently: the more screen-based peoples’ lives become, the more they value physical artefacts and experiences, he theorized.

At the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association convention held last fall in Tacoma, Wash., I learned that the people who love books enough to consecrate their lives to them have noticed this, too. With a gaggle of other authors, I was flogging my book in a massive speed-dating exercise that consisted of telling table after table of retailers what my novel was about. As I brandished my own beautiful hardback (of which more in a moment), we got to talking about the surprising appeal of hardbacks in this digital day and age. Over the past five years, they all agreed, hardbacks have not only held their own, they have gotten more beautiful. It’s almost as if, one bookseller mused, publishers understood that if one went to the trouble of producing or buying a printed book anymore, it had better be for a darned good reason. The very printness of print, it seemed, was its USP — its unique selling point. If a print book can’t offer something more than a cheaply produced paperback, the e-book wins the day. There’s simply no reason to buy it.

Can we define what this “more” is that a physical book provides? A lot has been written on this subject, usually centering on the notion of “tactility.” The tactile appeal of real ink on pages certainly plays a role. Most of us don’t know exactly why we love the soft oatmeal feel of good paper stock, the nubby ruffle of the deckle edge, the weight of the fabric-covered boards. It’s powerful, though, this hunger that we humans have for touch. Our skin is our largest perceptual organ, our first, most primordial sense; stroking a pet, or a page, releases occitocin, the hormone that brings joy. Even so, I’m convinced that the hold of the book goes even deeper. The best books give readers a profound aesthetic and intellectual experience, like our 15th century Bible: they are objects of both beauty and permanence.

As Hannah Arendt observed, mankind is homo faber: man as maker. We are tool-makers, art-makers, and respond to what we make, especially those things that are well made. What makes an object attractive, desirable — in a word, beautiful — if not each detail that reveals the care, the close attention of its maker? The evidence is all around us, from coveted Apple products hyper-designed by an obsessive Steve Jobs to luxury handbags and brushed-steel German kitchens. Nor is the pleasure we derive from such beautiful objects only aesthetic. Beauty is a kind of cognate for excellence: we are also viscerally responding to the maker’s attention to quality, which signals a certain kind of seriousness. Decades later I still recall the Heritage Library set of classics in my parents’ living room. Handsomely set in type, stamped with gold embossing and illustrated with powerful black woodcuts, these books sent the clearest message with their heft and beauty: pay attention, this is good. I should mention here that the gorgeous black textura letters of The Gutenberg Bible were not the first metal letters in the world; Gutenberg’s first efforts were crude, unlovely. It took time and extraordinary focus and skill to craft those letterforms we so admire, most likely the work of Gutenberg’s apprentice, Peter Schoeffer, a gifted calligrapher.

The painstaking work of craftsmanship thus results in things we can hold and admire. And hidden deep inside this tactile pleasure is the source of its real power. A well-made book, like any well-made thing, exudes a sense of permanence. The better it is made, the longer it will last — perhaps for centuries. In letterpress printing, this idea is captured by what printers call “the dwell:” the moment when inked metal letters touch the sheet. The letters dwell upon the page, as we dwell upon a word, or musicians dwell upon a note. It’s a word that marries a sense of duration, of permanence, to the act of fastening a text upon a sheet. Which texts do we choose to treat this way? The answer, I think, is obvious. The deeper, more universal, and important the “content,” the more we wish to grant it permanence. What we enshrine in print are texts we truly cherish, and deem sacred. This impulse is as old as cuneiform and scrolls, as old as the first prophets of the Abrahamic religions, instructed to preserve the Word of God. “Serious readers,” too, are members of this tribe. For is it not they — we — who felt most stricken at the thought the book had died, who perceived it as an existential threat? To some of us, it is literature itself that is sacred, insofar as it has become the place we turn for meaning, and for explication of the world.

The permanence of this heritage is an ever-present concern. We are haunted as we should be by the loss of the library of Alexandria, and by the sheer chance that saved the classics of antiquity in Constantinople. I for one am loath to hand our civilization’s most priceless works over to a digital “cloud” that will vanish when the gas runs out. The most important thing to remember about Gutenberg’s world-changing invention is not that it spread learning, or even democracy, the historian John Man reminds us. It is that printing gave mankind the means to preserve what it could not preserve before: “the entire cultural DNA of our species.” We turn away from such a gift at our own peril.

Over the nearly 2,000 years of its existence, the book has shaped us as effectively as we have shaped the book. There’s increasing evidence that the physical form of the codex mirrors the processing operations of the brain, a fact that should not surprise, considering the two have co-evolved. And this very permanence finds an analogue in the reading mind: our brains, it turns out, are wired to better store and retain what we read in print than things we read on screen. A print book conveys the meaning of a text uniquely. Its multiple sensory aspects — size, paper stock, ink, impression, art, typography — encode a staggering array of information. This physical structure creates a spatial construct for the mind that helps it navigate, according to Anne Mangan, a Norwegian reading researcher. It is useful to me to think of a printed book as a landscape through which the mind roams, touching branches, remembering paths. Like the internal “memory palaces” that medieval scholars used, the physical spaces of the book function as aids to recall. Turning pages helps us build “a scaffold on which memory and information are automatically arranged,” says Mangan.

The science is by no means settled. But it appears the physical space of the book both enourages us to focus in a way we do not on screen, and gives us clues — how far we’ve gone, where on the page that quote appeared — that help us to better remember. There is a third element that, to me, is equally compelling: a book we crack with our two hands creates an actual physical space for reverie that functions as an oasis outside daily life, a cocoon in space and time. An e-book can perform this function too, although I wonder if it takes us quite as far away. After all, these tactile qualities are part and parcel of the world the book creates. In the end, refusal of the e-book comes down to a refusal of sensory impoverishment. With all the senses we possess, why settle only for the eyes?

It’s no accident that we’re currently witnessing a revival of the handmade in every field, from handicrafts sold on Etsy to Maker Faires where the digerati escape to shape things with their hands. It is especially gratifying to see this happening in the arts of the book. The past decade has seen a huge boom in letterpress printing and bookbinding; young people all over the world are rediscovering the joy of making books as Gutenberg once did. “I can only liken it to making music yourself or cooking,” says Erik Spiekermann, a renowned typographer who has just opened a letterpress studio in Berlin. “Setting your own type is an essential experience, like making your own pizza, preparing your own food.” We readers, too, are drawn to these basic materials; we too yearn to hold a well-made book in our two hands.

This past spring I watched in wonder as the designers at Harper Books expressed that love of craft in their own work. Perhaps it stems from the fact that the founding Harper brothers were themselves printers: a case of type is displayed in the firm’s new offices on lower Broadway. Even so I was unprepared for how my story of the making of The Gutenberg Bible would inspire the people charged with putting it in print. It was as if the subject itself called forth the highest degree of craftsmanship, from exquisite page design to deckle edges and a die cut on the cover. They understood, I think, that a book about the first great book must strive for that same excellence and beauty.

I feel confident that there will always be a place for books we touch and hold. Some of us will read on phones or tablets; others will keep reaching for the real thing, the same way the great medieval printer Anton Koberger imagined his customers doing in 1493, when he sent out his Nuremberg Chronicle with this printed wish:

Speed now, Book…

A thousand hands will grasp you with warm desire

And read you with great attention.

Image Credit: Wikipedia