David Foster Wallace lives! How else could one explain the long-distance friendship that grew up between me and a person I have not yet met in person, and would probably never have known existed if it were not for our shared obsession with Wallace’s fiction? I am an anthropologist and filmmaker based at the Goeldi Museum of Belém do Pará in the Amazon region of northern Brazil, and got hooked on Wallace while reading Infinite Jest on the tiny screen of an iPod during an expedition to a Kayapó indigenous village. Caetano Waldrigues Galindo is a James Joyce specialist who teaches linguistics at the Federal University of Paraná in Curitiba, in southern Brazil, and who has just finished translating Infinite Jest into Brazilian Portuguese.

Galindo kept a blog about the year-long translation process, a piece of Brazilian Wallaciana that was picked up by the Howling Fantods website and fan list-serve, Wallace-1 — my haunt and halfway house ever since finishing IJ (though it is apparently not finished with me) — and…Voilà.

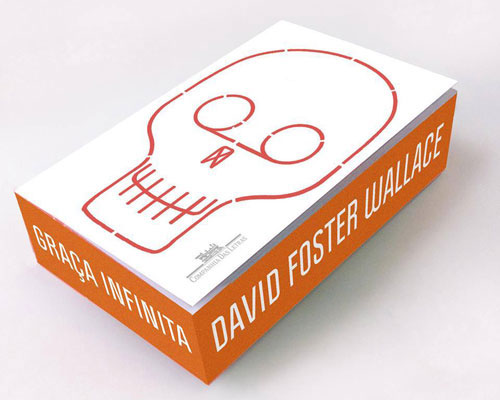

Companhia das Letras, Brazil’s premiere publisher of literary fiction and nonfiction, now part of the Penguin/Random House group, is bringing out a luxurious hard copy edition of Graça Infinita, Galindo’s Portuguese translation of Infinite Jest, on November 28. Companhia das Letras first introduced Wallace to Brazilian readers in 2005 with their publication of José Rubens Siqueira’s translation of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. Galindo has translated more than 30 books in all, including James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, Tom Stoppard, and Ali Smith, and is now busy on Wallace’s posthumous novel, The Pale King.

Companhia das Letras, Brazil’s premiere publisher of literary fiction and nonfiction, now part of the Penguin/Random House group, is bringing out a luxurious hard copy edition of Graça Infinita, Galindo’s Portuguese translation of Infinite Jest, on November 28. Companhia das Letras first introduced Wallace to Brazilian readers in 2005 with their publication of José Rubens Siqueira’s translation of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. Galindo has translated more than 30 books in all, including James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, Tom Stoppard, and Ali Smith, and is now busy on Wallace’s posthumous novel, The Pale King.

To celebrate the release of Wallace’s landmark novel in Brazil, I conducted the following interview with Galindo — still virtually, via email. But I hope to meet him in person, finally, at the official book launch, where I also plan to show a short samizdat-inspired film.

David Foster Wallace is still among us, and his singular voice will soon be heard by millions of new readers in Brazil.

Glenn H. Shepard: You seem to prefer translating works and authors that are not only essentially “untranslatable,” but also notoriously verbose: Joyce, Pynchon, now Wallace. Are you a masochist, or do you just enjoy intense mental activity?

Caetano W. Galindo: Well, apart from Ulysses, all I’ve done is translate what my editors give me to do. Ergo, I cannot be considered a masochist: they’re the sadists! But yes, this is the kind of literature I like, and thus what I read — and “write” — best. I think my publishers have found this to their liking. And yes, I really do enjoy the acrobatics. It’s kind of like chess: it’s much more fun to play against someone who’s better than you are, even though you may end up losing. I like being forced to reach, to face problems I would not have conceived myself. I enjoy trying to recreate puns, acronyms, styles-within-styles, multiple voices: you know, all the hard stuff. What can I say? Back to the masochism hypothesis…

Caetano W. Galindo: Well, apart from Ulysses, all I’ve done is translate what my editors give me to do. Ergo, I cannot be considered a masochist: they’re the sadists! But yes, this is the kind of literature I like, and thus what I read — and “write” — best. I think my publishers have found this to their liking. And yes, I really do enjoy the acrobatics. It’s kind of like chess: it’s much more fun to play against someone who’s better than you are, even though you may end up losing. I like being forced to reach, to face problems I would not have conceived myself. I enjoy trying to recreate puns, acronyms, styles-within-styles, multiple voices: you know, all the hard stuff. What can I say? Back to the masochism hypothesis…

GS: How did you first learn about David Foster Wallace’s work? What else of his have you read? Why did you decide to start with Infinite Jest?

CWG: I got to know about IJ when I was deep in my Ph.D. thesis on Ulysses. It was a time in my life when I thought nothing post-Ulysses was worth the effort: I was a real bore back then! “Badness was badness in the weirdest of all pensible ways,” as good ol’ Jim J. would have it. Then I heard about this huge book, and many people I respect said I should check out. And so I did. That was 2005. I got hooked. After that I read pretty much everything Wallace wrote, and everything people were writing about him. When I sat down to translate IJ, I had read the whole book twice, and was deeply familiar with Wallace’s voice and “tricks.” As a matter of fact, my fascination with the book was probably what landed me the job as a translator for Companhia das Letras. André Conti, the editor at Companhia das Letras who kinda headhunted me for them, is a big Wallace fan. From the moment I was hired in 2008 we had this dream of publishing IJ in Brazil.

GS: How long did the translation take? What was your daily routine? Did you keep your deadline? Did you ever reach a point where you thought you might give up?

CWG: It took me one year, which is actually pretty fast, considering [Ulrich Blumenbach spent six years on the German translation]. I was only able to do it so quickly because of my previous familiarity with the book and with Wallace’s writing in general. I did not have a daily routine: I’m a college professor, and that takes pretty much all my time. Whenever I could manage to get a few free hours I would go at it for some high intensity translation. During that year my mother also died, after a very long struggle with cancer. Looking back — what with those final weeks in the hospital with her, and the time it took me to get back to real life afterwards — I almost don’t know when it was that I translated all those hundreds of pages. But then again, one way or another, this is true of every book I have translated. I begin not knowing how I will be able to do it, and end up not knowing how I was able to do it. But I did keep my deadline, with one week to spare. I never thought about giving up. Even in those days after my mother’s death, the perspective of having this huge work to go back to was a real incentive. Kind of a reality booster, you know? And something else, as well: a kind of solace, I guess. The book helped me keep going…

GS: Very sorry to hear about your mother: that must have been tough. What was the most difficult passage in the book to translate?

CWG: Off the top of my head? Kate Gompert. It almost kills you, being inside her head for so long.

GS: How did you deal with Wallace’s erudite vocabulary? What about all that sketchy French?

CWG: Well, I like words. Funny, strange, exotic words. I teach the history of the Portuguese language at the Federal University of Paraná. So I have deep…ish pockets myself in that department. The problem with the French, though…As a French major, I just couldn’t turn a blind eye to all the mistakes. At first I thought I might exert the prerogative Francis Aubert claims for the translator as “final copyeditor.” However, in the end, and after talking to Herr Blumenbach, I decided to leave the mistakes, not knowing what else to do. Was it intentional? Am I to decide? Let the reader sort it out.

GS: What did it feel like to spend so much time, so deep inside such a complicated plot, and such a complicated mind?

CWG: It was a fascinating process. And in this book in particular, the sensation of being “inside” someone’s head (pun intended) is really overwhelming. I love the book even more today, after having unraveled and re-raveled its inner workings. I could feel the plot: I could almost touch it. But you have to remember I was not working on a regular daily schedule. When I could, I clocked 10 hours. But then, the next day, I wouldn’t have time to translate at all, since I would have papers to grade, or other things to write, or students needing help, classes to teach. I think that helped keep me safe. Wallace’s (or Incandenza’s) mind seems to be exactly what the book is: a beautiful labyrinth. Enchanting. But dangerous…

CWG: It was a fascinating process. And in this book in particular, the sensation of being “inside” someone’s head (pun intended) is really overwhelming. I love the book even more today, after having unraveled and re-raveled its inner workings. I could feel the plot: I could almost touch it. But you have to remember I was not working on a regular daily schedule. When I could, I clocked 10 hours. But then, the next day, I wouldn’t have time to translate at all, since I would have papers to grade, or other things to write, or students needing help, classes to teach. I think that helped keep me safe. Wallace’s (or Incandenza’s) mind seems to be exactly what the book is: a beautiful labyrinth. Enchanting. But dangerous…

GS: What do you make of IJ’s notoriously indeterminate plot? Did your interpretations or understandings affect your translation?

CWG: As for the plot: well, I’m a translator. The guy designs a labyrinth. I reproduce the design with my own bricks and mortar. It’s not my job to point any ways out, if there are any! As a reader, I do have my interpretation, but that’s not what matters. As I tell students all the time, the translator’s job is not to find an interpretation, but to try and find all interpretations, and keep these possibilities open for this new reader who’s going to have only the translation as a guide. But, back to plot, you basically follow the original steps. No biggie. There’s one thing I regret, though. A student of mine, Ana Carolina Werner, pointed it out to me. The final two words of the book, referring to the tide being “way out,” also suggest the possibility of exit, escape. But there was no way to keep this double entendre in the Portuguese.

GS: How did Wallace’s death affect you, and your understanding of his work? What was it like to spend a whole year channeling a wraith?

CWG: Well, it was a huge shock, for me and for everybody. It was like Primo Levi, or that moment in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors when the subject of the documentary (inspired by Levi) commits suicide. “How can this be?” The only man who seemed to be showing us, through all that was modern and new in his literature, a possibility for an old-fashioned answer to the great existential questions that have guided philosophers and writers for ages. And he kills himself. Probably everyone who reads this interview felt something similar. When I heard the news, I turned off my computer and played the piano for an hour or so, trying to empty my mind, or fill it with something else: I didn’t know what to think. But back to the point: it does affect our reading. It would be a lie to say it doesn’t.

His literature is profoundly human, and profoundly personal, meaning that there is direct one-on-one involvement. You constantly feel like you are dealing with Dave himself, the person. All the scenes with Kate Gompert, the descriptions of pain, depression, pain…The fact of his suicide doesn’t clarify, it only makes it tougher. But it doesn’t change the book’s potential. Because, in spite of personal “answerability” (to use Mikhail Bakhtin’s word), he is not writing a memoir. He is creating worlds, characters, lives, and all that lives on, independently. It may change how we think of him, and of his relation to his subjects. But the book stands.

About “channeling a wraith” — Yes: a nice way to put it. In fact, it’s not an easy expression to translate into Portuguese. But that’s really what it was like. It felt very close, as if I were in his head. Or in Hal’s, or maybe Jim’s, but which were definitely inside his. I kept mourning, lamenting the fact that he was not there for me to write to him during the process. Even though I know he was not that keen on thinking about his translations. But I would have written. I wrote him a long letter once. Before. But I never sent it.

GS: An independent Portuguese translation was published in Portugal prior to your own. Have you read it? How different is it from your own? Do you think Brazil warrants its own translation?

CWG: I haven’t read it, though I have talked to the translators. Very nice folks! A very competent job as far as I can tell — they most kindly sent me their book. About the two translations: First, there is the problem with rights. You do not buy the rights for the Portuguese language as a whole, only for the country. So, officially I can’t buy their translation in Brazil, and vice versa. Second, and perhaps more importantly, Anglophones should be reminded that the gap between European and Brazilian Portuguese is much wider than what you have between British and American English. As a matter of fact, I would be incapable of writing anything (translation or original) that would ever “pass” in Portugal as anything other than Brazilian vernacular Portuguese. Alison Entrekin, for instance, who is the greatest Portuguese-to-English translator alive today, is Australian and works for British and American publishers. I don’t know anyone who could do that in both European and Brazilian Portuguese.

GS: In the European Portuguese translation, the title is rendered as Piada Infinita, while you translate it as Graça Infinita. Explain. Doesn’t graça have mystical overtones, in the sense of religious grace?

CWG: Well, that’s the one I was afraid of…So here goes. First, there is the question of Brazilian versus European usage. Both piada and graça refer to jokes, or anything that is funny. But graça also has an extended meaning cognate with English “grace,” both in the sense of religious grace and physical gracefulness. In Brazil we have an expression, ‘não tem graça’, which means both “that’s not funny” but also, “that’s not nice”; there’s also ‘sem graça’ which means “awkward,” or literally “without grace.” Europeans use piada in almost exactly the same expression, não tem piada, “that’s no joke, that’s not nice.” So in Portugal, piada has a more extended range of meanings, somewhat like graça in Brazil, whereas piada in Brazil means only “joke.” So we couldn’t go there. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the expression “graça infinita” was used by Millôr Fernandes in his Brazilian translation of Hamlet. We were toying with the title Infinda Graça, which uses an older, more archaic word for “infinite,” and which sounded good to my ears. But the Hamlet factor was a good argument, and we ended up with Graça Infinita. Finally, you are right, graça does sound religious-y. We didn’t have that many choices to begin with, and I don’t think this “mystical” undertone is wrong. Is it? There may be no “God” figure central to the novel’s narrative. But, sorry! I really do like this idea that the ineffable, the mystical (as good old Ludwig W. would have it) is always there, always lurking, always tempting. So I stand by our choice!

CWG: Well, that’s the one I was afraid of…So here goes. First, there is the question of Brazilian versus European usage. Both piada and graça refer to jokes, or anything that is funny. But graça also has an extended meaning cognate with English “grace,” both in the sense of religious grace and physical gracefulness. In Brazil we have an expression, ‘não tem graça’, which means both “that’s not funny” but also, “that’s not nice”; there’s also ‘sem graça’ which means “awkward,” or literally “without grace.” Europeans use piada in almost exactly the same expression, não tem piada, “that’s no joke, that’s not nice.” So in Portugal, piada has a more extended range of meanings, somewhat like graça in Brazil, whereas piada in Brazil means only “joke.” So we couldn’t go there. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the expression “graça infinita” was used by Millôr Fernandes in his Brazilian translation of Hamlet. We were toying with the title Infinda Graça, which uses an older, more archaic word for “infinite,” and which sounded good to my ears. But the Hamlet factor was a good argument, and we ended up with Graça Infinita. Finally, you are right, graça does sound religious-y. We didn’t have that many choices to begin with, and I don’t think this “mystical” undertone is wrong. Is it? There may be no “God” figure central to the novel’s narrative. But, sorry! I really do like this idea that the ineffable, the mystical (as good old Ludwig W. would have it) is always there, always lurking, always tempting. So I stand by our choice!

GS: What about Infinite Jest do you think will appeal to Brazilian readers? Is there any Brazilian author who could be considered a “soul-mate” to Wallace, in some sense? Has Wallace exerted a notable influence on Brazilian literature? What Brazilian authors, contemporary or otherwise, would you recommend to Wallace fans?

CWG: I think Graça Infinita (let me use my title, now that I’ve justified myself!) is of immense interest to anyone who is thinking about or wants to think about what it means to be a human inhabitant of this particular nook of world history. I hope readers in Brazil can see that, and can find in the book all it wants to communicate to us at this deep, human, level. As for a Brazilian “soul-mate”…well, here in Brazil, we have yet to arrive at such gargantuan hubris! Our best writers, right now, seem to be more concerned with short-ish studies. But we do have a new generation of very promising prose writers. Among them we find lots of readers of Wallace. People like Daniel Galera, Daniel Pellizzari.

Wallace’s influence is felt in a number of ways. Wallace is probably the best prose stylist since Pynchon or Don DeLillo. But like both of them, he is also a deep thinker. And what he said, through his fiction and in his essays, is already a big influence on a whole generation of writers, even here. Brazilian authors I’d recommend? Hmm…There’s always the great Machado de Assis (I suggest Epitaph of a Small Winner)…João Guimarães Rosa, most definitely. The João Ubaldo Ribeiro of Viva o povo brasileiro. Someone more contemporary? The André Sant’Anna of O paraíso é bem bacana“. Me… :)

Wallace’s influence is felt in a number of ways. Wallace is probably the best prose stylist since Pynchon or Don DeLillo. But like both of them, he is also a deep thinker. And what he said, through his fiction and in his essays, is already a big influence on a whole generation of writers, even here. Brazilian authors I’d recommend? Hmm…There’s always the great Machado de Assis (I suggest Epitaph of a Small Winner)…João Guimarães Rosa, most definitely. The João Ubaldo Ribeiro of Viva o povo brasileiro. Someone more contemporary? The André Sant’Anna of O paraíso é bem bacana“. Me… :)

GS: Have you read translations of IJ into other languages?

CWG: No. I’m only human!

GS: What’s next? Any plans to tackle Roberto Bolaño?

CWG: I’m already at work on the musings of our nice friend “Irrelevant” Chris Fogle right now. My translation of The Pale King should be ready next year. But I’ll put that job on hold for the time being, because we want to publish a new translation of Dubliners, together with my own “Guide” to Ulysses for Bloomsday 2015. I may or may not translate Pynchon’s most recent novel, Bleeding Edge. If my mentor and hero, the great Paulo Henriques Britto, is too busy, maybe I’ll get it. I’m hoping to do my fourth Ali Smith translation sometime next year. As for Bolaño: No: I don’t translate from Spanish!