1.

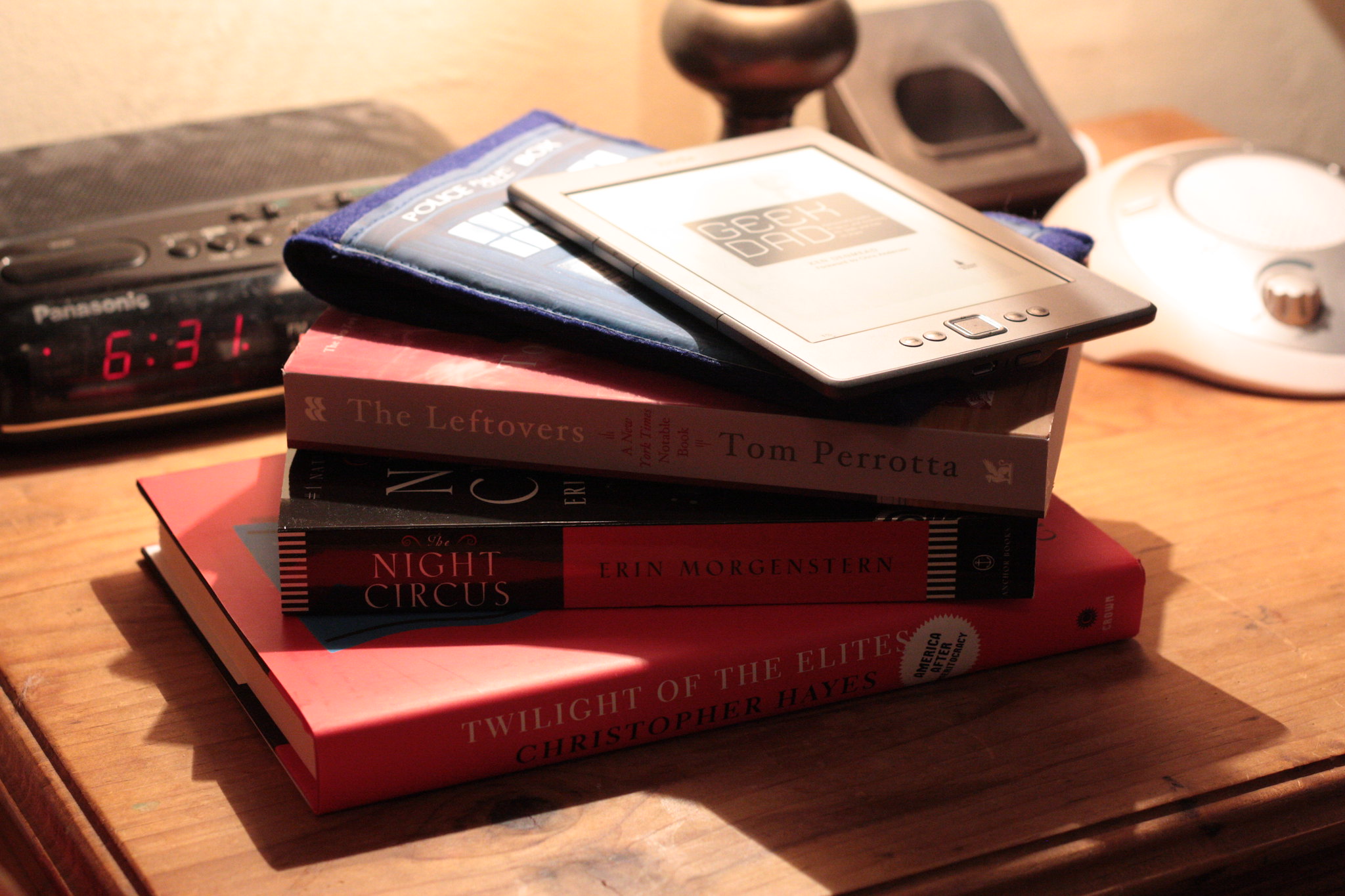

As usual, you’re talking with your friend about books. “Have you read it?” she asks. “No,” you say, “but it’s on the nightstand.” It’s on the nightstand. That’s code for, I’ve made mental note of it. Or It’s on my list but not a priority. Or even, I actually own it, and I’ll be reading it next. Regardless, for me, It’s on the nightstand has always been metaphorical — an abstract and elastic category of Books I Hope To Read.

That is, until recently.

You could call it an “alcove,” but it’s not big enough for a queen-sized bed. The full-sized has worked just fine, but the piles of unshelved books — on the floor, on the dresser, on the dining chairs, in the bathroom, on top of the puppy crate for godssakes — haven’t. I wanted a nightstand.

And so, an end table was repurposed. Finally, I have an actual nightstand.

What’s on the nightstand? Suddenly the question is not so abstract. Of the mess of books that has been unsystematically scattered throughout my home, and my life, which ones will make it to the nightstand? In what order will they be stacked?

Perhaps most importantly: how will I decide?

2.

A mini-debate recently bloomed among colleagues at the college where I teach, after the department administrator sent around a brief and innocent-enough email: would we please send changes or additions to the attached post-grad Suggested Reading List? The list, she reminded us, would be distributed to graduating seniors; a deadline was specified.

“Are the students asking for this?” Professor B wrote. Was it perhaps odd to foist such a list on departing students, “a noodging sort of gesture from teachers who can’t let go?” Professor H concurred, quoting Professor L: “Why ask for a booklist now, dear graduates? We’ve given you the tools to read and to make discriminations among the various books you encounter: So feel free to fly away from the comfortable nest of your undergraduate English Department and read what you want and when you want.”

Off-line conversations ensued. Professor H came back with an idea:

“[O]ne of my main goals in the classroom,” she wrote, “is to teach students to go from one book to another all by themselves; I am never so dejected as when seniors complain they have no clue as to what to read next…What if we encouraged our seniors to put together a list of books for the rest of our majors?” A week later, Professor H further articulated her thinking: “It won’t be enough, of course, to ask the grads what books they recommend. The real question is how they found them.”

3.

To go from one book to another all by themselves. It sounds simple enough. As a young person just entering the world of post-academy literature, the challenge may be discerning “what’s good.” In youth, there is a blessed naiveté about this, a hunger for objective, definitive recommendations from an authoritative source. In graduate school, when a professor first challenged me to “create your own map of literary influences,” it was indeed a revelation: the image I remember conjuring was of lily pads — each of us in our own deep black pond, bug-eyed and hopping from one pad to another. Sometimes just one pad over, sometimes a greater leap to the far shore. Apparently random, and yet mysteriously considered.

As we get older — as the nature of our work and passions specifies, as our aesthetic palates grow more particular — we understand that, given the sheer number of artful and compelling books in the world relative to the time we have on the planet, “good” is more contextual than absolute. Deciding what to read next is thus as much about Knowing Thyself as Knowing Literature. School attempts to teach the latter; it’s the self-knowledge that we must develop on our own, over time.

And so, in my humble opinion, the process by which you decide what to read must not be outsourced — to your professors, to reviewers or awards, to online algorithms. An external source can’t tell you what you need to read next any more than a spouse can tell a pregnant partner what she’s craving to eat; what will satisfy. Read what you want and when you want. Choosing what to read is about attuning yourself to what it means to be nourished. By this I mean confronted, changed, filled, emptied, engrossed, surprised, instructed, consoled — all these. You. At this moment in time.

4.

What should I read next? It is not a casual question. We are not frogs. We are chasing something more profound than flies. Every time I finish a book and consider what to read now, it feels…important.

Since I am not so much looking for a foolproof test of a book’s “objective” quality, my decision process is no more suitable for you than my nightstand list. Nevertheless, here it is — my provisional, evolving list of the (sometimes absurd) ways I decide/have decided what to read next:

A. The 25-Page Test

Standard trial run. I bought the book on impulse; it’s been lying around for a while. I pick it up and start reading. Am I eager to read page 26 (even better: did page 26 come and go without my noticing)? Am I stopping to scribble in my notebook because the book is sparking responses that matter enough to write down? Or — have two paragraphs gone by and I don’t know what I just read (in which case something is evidently not clicking).

B. The Three-Book Shell Game

Okay, the truth is, I bought three books on impulse. I lay them out side-by-side. I stare at them. Which one should get the trial run first? I stare some more. I pick up each one, feel it in my hands — heft, cover material. I look at the cover for some time. Sure, there is that two-second impression; but there is also the three-minute study and consideration. The emotions and ideas it evokes. I skim the jacket copy but not too closely. I am not interested in the publisher’s sell job but rather words or phrases that resonate, with me, right now, for whatever reason. I lay them out again. I wait. I swear to you, one of them starts to levitate.

C. Narrative Point-of-View/Voice

As reader, writer, and teacher, for me, narrative POV is perhaps the most intriguing, and most important, feature of any work of fiction. Usually, I am primed for something specific: first person or third person; omniscience or (in James Wood’s terminology) free indirect style; vernacular or formal, contemporary or non-contemporary; verbal density or spareness (the author who achieves these simultaneously always wins). When narrative voice is a driving factor, three or four pages is usually enough to determine Yay or Nay. Do I want to hear this voice speaking for the next two days or two weeks? Do I need a voice I can “trust,” insightful and articulate? Or something less stable, a wild and deeply subjective ride?

D. Bookshelf Staring

I’ve just finished a book, and I’m on a reading roll. I stand in front of my bookshelves. Like yours, mine are “organized” in a particular way that would make very little sense to anyone else. I change up this organization from time to time, and sometimes this staring prompts reorganization. Sometimes the reorganization becomes part of the process of choosing — handling the books and moving them around as a way of reorganizing my mind. At the moment, there is the not-yet-read section. But I stare at the whole canvass of books, not just that one section. The book I’ve just read is still buzzing in my mind; if it was great, it’s buzzing in my body, too. I want more of that buzzing, but differently. The last book did X so well, so interestingly. I’m intrigued by X’s impact and also interested in how X would read if it was plus Y and minus Z.

I step back, lean in, repeat. I swear to you, one of the books starts to vibrate.

E. Loved This Author, Want More of Same, Read Everything in the Author’s Oeuvre

This is the most exhilarating — like falling love. The last book did X. I want more and more and more of X. I am learning something here, seeing something new, growing intimate with characters and ideas. Maybe I haven’t identified what, exactly, was so captivating, so I read on to find out. More, more, more. Sometimes I’ll read them in order of best reviewed to worst reviewed; sometimes vice versa (reading the supposedly minor works of a favorite author can be particularly illuminating); sometimes chronologically; sometimes via the three-book shell game.

F. Wishlists

I do keep wishlists, haphazardly. Or, I used to. When I’m stumped, I’ll log on to Goodreads or Audible and see what, at some point in time, I decided I might someday like to read. Then I proceed with Item D above, the online version of bookshelf staring. With audiobooks, a two-minute sample is usually available — the audio version of the 25-page test combined with the narrative voice test.

(As I write this, I am reminded of the usefulness of online wishlists. It’s a place to be impulsive about books, without opening your wallet. And looking back on your wishlists is such an interesting journey in itself: Vasily Aksyonov? Dorothy Day? Suttree. I craved these books enough to click them. What was I thinking about at the time? Hmm…)

(As I write this, I am reminded of the usefulness of online wishlists. It’s a place to be impulsive about books, without opening your wallet. And looking back on your wishlists is such an interesting journey in itself: Vasily Aksyonov? Dorothy Day? Suttree. I craved these books enough to click them. What was I thinking about at the time? Hmm…)

G. The “Should” Lists

I really should read Thackeray. I really should read Vollman. I really should read The Goldfinch. Well, maybe. I was glad I pushed myself to read Faulkner and Proust and To the Lighthouse; less so Philip Roth and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I’m still pushing with Thomas Mann, the verdict is out. It’s good to ask yourself why you should read it. So you don’t feel stupid in a workshop or at a cocktail party? Or maybe because your favorite author from Item E above was deeply influenced by it. There are better and worse reasons for force-reading.

If you are a professional literarian of some sort, there are more “shoulds” to contend with: you must teach, review, converse about certain books. I’ve been fortunate to “have” to read Jean Stafford, Esther Freud, Henry James, Carson McCullers, Giuseppe di Lampedusa, Steven Millhauser, Miranda July, Sherwood Anderson, on and on (in the cases of Lampedusa and McCullers, it led to Item E). In other words, there is certainly such thing as benevolent authority, and required reading can be a blessing (that is, when it’s not a curse).

H. Recommendations from Friends

This, I confess, is one of the least successful categories. It’s not that my friends don’t have good taste. That many of them are thoughtful and discriminating readers may be the very problem: their passions are as contextual and idiosyncratic as mine. It would be, in a way, a little weird if the books they raved about were books that I would rave about, at the same moments in our lives. (Recommendations seem to work better, I find, when a friend talks about something he read some time ago, within the context of current conversation — as opposed to, “I just read this great book!”).

I. Bloom

My shameless plug. When Lisa Peet and I started writing about “post-40 bloomers,” there was a sense of mission, of trying to bring an alternative perspective to the table. Little did we know how many important writers — important to us personally — we’d discover along the way. For me, to name just a few: Harriet Doerr, William Gay, Spencer Reece, Shannon Cain, Edward P. Jones, Virginia Hamilton Adair, W.M. Spackman, Robin Black. And don’t get me started on Jane Gardam (I cannot stop talking about Jane Gardam — Item E bigtime).

J. The Dessert Selection

J. The Dessert Selection

Sometimes reading is about imaginative and intellectual expansion, the difficult pleasure that is, in the end, transformative and satisfying. But sometimes you have a reading window in which you want to treat yourself to an easier pleasure. Life is hard; you want to be carried away, both far and deep. As with physical nourishment, occasional dessert is as important for your health as kale. Endorphins or something? But let me be clear: a truly pleasurable dessert is still made of excellent ingredients, not junk. Me, I’ve been working pretty hard this summer; for this last week, I’m delving into Bring Up the Bodies.

5.

So, go throw darts at your bookshelves. Read 10 pages aloud. Stack up your wishlists. Read what you want when you want. If you don’t have one, get yourself a nightstand.

Image Credit: Flickr/seanfreese.