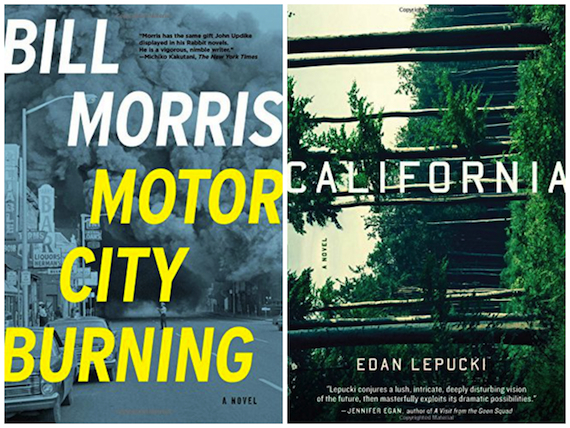

This week, two of our staff writers here at The Millions are publishing novels. California, Edan Lepucki’s debut, is set in the near-future in northern California, where a young couple scratches out an existence after a series of environmental and economic calamities. Thanks to Sherman Alexie and Stephen Colbert, the book has generated a typhoon of buzz, leading to brisk pre-sales. The San Francisco Chronicle calls the novel “ambitious, powerful, frightening.”

Motor City Burning, Bill Morris’s third novel, is set during the 1968 baseball season in Detroit, where a white homicide cop is pursuing a black suspect, a disillusioned former civil rights activist, in the last unsolved killing from the previous summer’s apocalyptic riot. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review, writing that the novel displays “acute insight into the era’s fraught climate.” And Kirkus Reviews has called the story “an intense cat-and-mouse game.”

Edan, who lives in the San Francisco Bay area, and fellow Millions staff writer Bill, who lives in New York City, recently had a conversation via email about the joys and perils of writing novels and shepherding them to publication. Here is that conversation:

Edan Lepucki: I really enjoyed Motor City Burning! It’s such a deftly drawn character study that also doesn’t scrimp on plot and big themes, like justice, purity of aims, and loyalty. The novel both invokes Detroit in the 1960s and also traffics in some classic crime novel tropes – but without succumbing to those tropes altogether. Do you see this is as a historical novel, a crime novel, or neither, or both? Or, really: how does its historical element affect its plot elements?

Edan Lepucki: I really enjoyed Motor City Burning! It’s such a deftly drawn character study that also doesn’t scrimp on plot and big themes, like justice, purity of aims, and loyalty. The novel both invokes Detroit in the 1960s and also traffics in some classic crime novel tropes – but without succumbing to those tropes altogether. Do you see this is as a historical novel, a crime novel, or neither, or both? Or, really: how does its historical element affect its plot elements?

Bill Morris: I’m glad you think I didn’t succumb to the old tropes. That was something I was definitely trying to avoid. I guess I see this as a “historical crime novel,” if such a genre exists, because my starting point was the events of the 1960s – the civil rights movement, the pop music, and, especially, the summers of 1967 and 1968 in Detroit – and using that history to tell the story of a crime that actually happened, the last of the 43 killings during the ’67 riot.

I want to get the smoke-blowing out of the way up front. So I’ll just say it flat-out: California is a novel about a dystopian future, somewhere in the middle of the 21st century, when violent weather and economic collapse have divided America into the haves, who live in gated communities, and the have-nots, like the young couple Cal and Frida who live in the wilderness, scratching out an existence. I never would have guessed this is a first novel – because the withholding and revealing of information is done so deftly. Also, at the level of the sentence, there is great assurance. I’m guessing a lot of rewriting went into making such a polished final draft. Am I guessing right?

I want to get the smoke-blowing out of the way up front. So I’ll just say it flat-out: California is a novel about a dystopian future, somewhere in the middle of the 21st century, when violent weather and economic collapse have divided America into the haves, who live in gated communities, and the have-nots, like the young couple Cal and Frida who live in the wilderness, scratching out an existence. I never would have guessed this is a first novel – because the withholding and revealing of information is done so deftly. Also, at the level of the sentence, there is great assurance. I’m guessing a lot of rewriting went into making such a polished final draft. Am I guessing right?

EL: Thanks, Bill! Reading yours, I could definitely tell you were not new to the novel dance: you write with such control and grace. It inspired me.

Most of the rewriting – and, make no mistake, there was a lot of rewriting! – had to do with plot and world building. I tend to write very clean first drafts, and what I have to work on later is the story. Thankfully, my characters were well in place, so editing was all about clarifying what had happened to L.A.; what the origins of Frida’s brother’s terrorist group were; and what happened to this enclosed outpost before Frida and Cal sought it out. My editor Allie Sommer had me write a timeline to make it easier to see the story more wholly. That helped; I usually write so intuitively, crafting pretty sentences and focusing on characters, that the story, the plot, gets neglected.

What about you? Did you know this novel’s architecture from the outset, or did it come to you as you wrote? How did you decide whose point of view to favor? Were black civil rights activist Willie Bledsoe and white detective Frank Doyle always the major players? What did it take to flesh them out into the complicated characters they are now?

BM: Your question about point of view brings back some painful history. This novel has been in the works, off and on, for 17 years. It has been through four titles, four agents, at least a dozen drafts, and more rejections than I care to count. In one draft, I tried to tell the story through alternating first-person voices, à la As I Lay Dying. This failure confirmed something I had long suspected: I’m no William Faulkner. Once I settled into a third-person omniscient voice – and worked to make myself invisible – things started to fall into place.

BM: Your question about point of view brings back some painful history. This novel has been in the works, off and on, for 17 years. It has been through four titles, four agents, at least a dozen drafts, and more rejections than I care to count. In one draft, I tried to tell the story through alternating first-person voices, à la As I Lay Dying. This failure confirmed something I had long suspected: I’m no William Faulkner. Once I settled into a third-person omniscient voice – and worked to make myself invisible – things started to fall into place.

As for architecture, I knew my central story was going to be the hunt for the person responsible for the last unsolved killing from the 1967 Detroit riot; but I wanted to frame that story around the Detroit Tigers’ championship season of 1968. The story got a jump-start when I learned that Opening Day of the ’68 season was postponed by two days in deference to Martin Luther King’s funeral. So right away, the civil rights movement and baseball were winding together. I also knew I wanted a young black man from the South as the protagonist, someone who had been in the trenches with the Freedom Riders and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, but got disillusioned with the movement’s leaders. Again, King’s funeral was the ideal way to introduce this character and his dilemma. Sometimes, when doing historical research, you get little gifts for your fiction. And as for fleshing out Willie Bledsoe, the burnt-out activist, and Frank Doyle, the white cop who’s after him, my main goal was to make both men imperfect, confused, and complicated. Detroit’s racial divide is one of the most complicated things in America, and I didn’t want there to be anything simplistic about it in this book.

Speaking of complicated, one of my favorite things about California is how Micah, the leader of the outpost you mentioned, got involved with a terrorist group that conducted suicide bombings Terrorists – especially eco-terrorists and guys like this “econo-terrorist” – make for fascinating fictional characters. I’m thinking of Kelly Reichardt’s new movie, Night Moves, and books like Jim Harrison’s A Good Day to Die, and Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. Are those characters interesting because of their moral ambivalence, their willingness to do wrong in order to do right? Or do you think it’s something else?

Speaking of complicated, one of my favorite things about California is how Micah, the leader of the outpost you mentioned, got involved with a terrorist group that conducted suicide bombings Terrorists – especially eco-terrorists and guys like this “econo-terrorist” – make for fascinating fictional characters. I’m thinking of Kelly Reichardt’s new movie, Night Moves, and books like Jim Harrison’s A Good Day to Die, and Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. Are those characters interesting because of their moral ambivalence, their willingness to do wrong in order to do right? Or do you think it’s something else?

EL: Wow, the journey of your book is astounding and is a good advertisement for tenacity and revision. And speaking of baseball, I loved the evocative descriptions of Tiger Stadium. I read them aloud to my husband, who is obsessed with the sport.

I love your interpretation of Micah. He was the most difficult character to write because I wanted to give him a humanity that persisted despite his evils, or perhaps was in danger of fading away because of said evils. Some readers have described him as a psychopath, but I don’t totally agree: Micah did at least begin with commendable ideals…and he also started out with something dark and damaged at his core. He is dangerous precisely because he is human: capable of being hurt and of wanting attention; driven by a desire to change the world but also a servant to an unquenchable ego. I wanted him to be a villain, but also a little brother. Frida can and can’t see his flaws because he is family.

Let’s talk about how your book got published after its long road. Who bought it, and how has the path to your pub date been?

BM: The book was bought by Jessica Case, an editor at Pegasus Books, a small independent publisher in New York City. The manuscript had been sleeping in a drawer for several years when I got a magazine assignment from Popular Mechanics in early 2012 – they wanted me to go back home to Detroit, talk to people, look around, and try to imagine what the city will be like a dozen years from now. I was very anxious that the assignment was going to be a bust, but when I got back to Detroit I was astonished by the energy, the enthusiasm, the sprouts amid the rubble. With Detroit so much in the news – and this was before the bankruptcy – I thought the time was right to try to give that old manuscript a pulse.

I revised the manuscript one more time and found a new agent, a human volcano named Alice Martell, who I’d met at the National Book Awards ceremony, where I’d gone to interview a client of hers who was a finalist. She agreed to look at my manuscript, she got it, and she sold it. The people at Pegasus have been amazing – not only Jessica’s editing, but the copyediting, the proofreading, and now the publicity push. Which reminds me, you did a couple of nice interviews for The Millions with your editor and copyeditor. Amid all the grim news about the publishing industry, I think we’ve both had pretty salutary experiences. Wouldn’t you agree?

EL: Yes, I too have had extremely positive experiences with my agent and editor and publicists at Little, Brown. I feel like they’ve put so much time and energy into making my book better, and getting it into readers’ hands. This book in many ways feels like a collaborative effort. I could not have gotten it out there on my own.

What was the editing experience with Jessica like? Allie, my editor, took me through a couple major revisions and she had very high standards. I learned a ton about revision from her. Was your editing experience similar to your previous ones, with your two other books?

BM: Jessica went over every word of the manuscript and made many small suggestions and several major ones – always stressing that they were suggestions, there for me to take or leave. I took almost every one because she’s smart and unbelievably thorough, and they made the book much better. Then the copyeditor, Deb Anderson, found new ways to improve the manuscript. And the proofreader, Phil Gaskill, caught inaccuracies and inconsistencies that never would have occurred to me. My first novel got a similarly thorough editing at Knopf, while my second got virtually none at Avon. Overall, this experience has renewed my faith in the publishing industry. People say nobody edits books anymore. Don’t believe them.

I just got finished reading today’s New York Times, and I was stunned to see a major feature article about you and California and how Stephen Colbert has taken up your cause as part of his ongoing campaign against Amazon on behalf of Hachette writers, including you. You mention in the article that the attention has alternated between being “icky” and “a fantasy.” Which side is winning out?

EL: Stunned is the right word – that’s how I feel! Mostly, the “fantasy” side is winning out; I feel enormously grateful and thrilled to have so much attention on my book. It’s so hard to get press for a novel, and this is just…just…crazy! I still feel badly that my good fortune is a product of this messy dispute between Amazon and Hachette. I wish I wasn’t the only author enjoying this bump; even though my fellow authors have been supportive and excited for me, I know there are many books that are getting a raw deal because of this dispute, and that does feel icky. But, yes, it’s really a spectacular turn of events. It just brings home for me how random it all is: there are tons of good books that don’t get much press. Why certain books take off like wildfire while others don’t is an enduring mystery to me. Right now I am just, again, stunned that California was plucked from the mountain of books. Also: wow, TV is still really powerful!

Now that your faith in writing fiction and publishing has been renewed, what’s next for you? What are you working on now?

BM: I’m back at work on one of the novels I couldn’t sell during that 17-year dry spell. Like California, it’s set in the near future, but in New York City. I don’t want to say much more, but the working title is Garbage: A Love Story. How about you? Are you working on something new, or is selling California taking up all of your time and energy?

EL: I recently returned to Ucross, an artists’ retreat in Wyoming where I started California. There, I continued working on a novel I began almost a year ago, but which I only work on in fits and starts (between revisions and publicity and motherhood, I guess). I have about 150 pages. All I’ll say is that it’s contemporary, and there are women in it. I haven’t written much at all for the past month, sadly, but I look forward to diving back in once this publication hullabaloo dies down.

BM: Well, this publication hullaballoo is a necessary evil. I just hope California continues to sell like Krispy Kremes, and I can’t wait to see what you come up with next.

EL: Same to you, Bill!