Reading Gonçalo M. Tavares, the Portuguese novelist who writes in detached, hyper-objective prose, can be like eating from a brilliantly curated cheese sampler. Each carefully cut wedge of cheese on the plate is given ample space from the others so that it can be savored distinctly, and ultimately ranked according to preference. In the more sophisticated restaurants, the chef will pair each cheese with a precise analog — a flavor of honey, a warm fig, a sprig of rosemary, a sliver of almond. Your enjoyment in consuming the cheese sample springs from this scientific arrangement, the grace and beauty of the experience assured because the chef’s palate is at once so elemental and so refined.

Consider this use of language, the way Tavares juxtaposes logical thoughts and sensory experience, in the novel Jerusalem:

Consider this use of language, the way Tavares juxtaposes logical thoughts and sensory experience, in the novel Jerusalem:

He smelled his way back to the barrel, then over to the grip; and now, in fact, having spent the requisite amount of time with his nose against its metal — feeling the slightly unpleasant heat radiating from the thing — sitting at his table, completely focused, in total silence, with no other thoughts in his head, Hinnerk found he was able to smell his own hands on the gun. The grip of a gun smells like a man — in this case like a man by the name of Hinnerk Obst. The smell of a man is a human smell, he thought, then went back to concentrating and inhaling. What a difference after the seemingly insignificant journey between the gun’s barrel and its grip: the barrel was free of any hint of humanity…it didn’t smell like a man, it smelled metal: a deeply intimidating smell, a smell you wouldn’t exactly call appetizing. But when it came to the gun’s grip — because of the human smell clinging to it — the smell of Hinnerk’s hand — there was something appetizing…a ripe, organic smell.

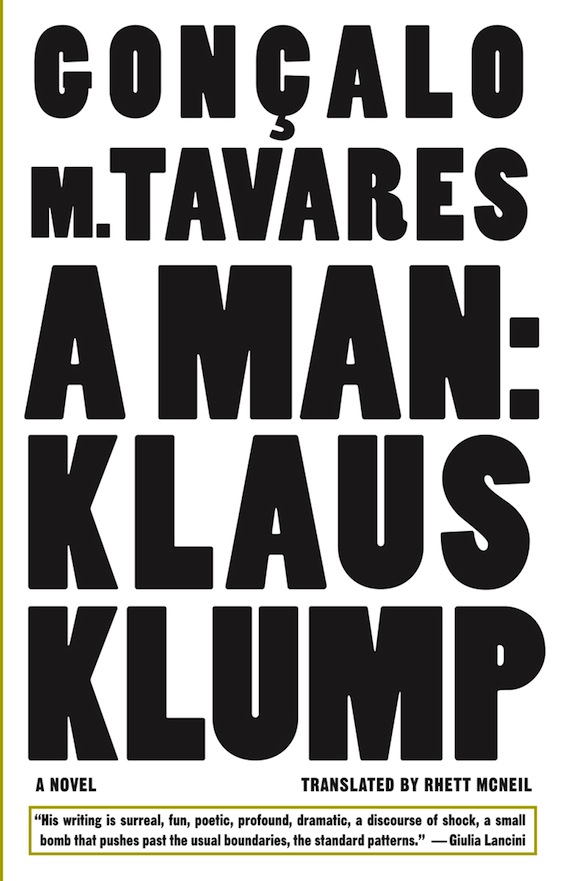

Tavares has been Portugal’s rising literary mestre since he was awarded the Saramago Prize at 35, nine years ago. American readers got their first taste of his startling prose and his obsessive interest in the dynamics of power—strength and weakness, mind and machinery — with Jerusalem, which Dalkey Archive published in 2007 in the English translation by Anna Kushner. That book was Tavares’s third in his four-part Kingdom cycle. Dalkey put out the last book in the series, Learning to Pray in the Age of Technique, in 2011 in the translation by Daniel Hahn, followed by the second, Joseph Walser’s Machine, in 2012, and now this month the first, A Man: Klaus Klump, which was published originally in Portugal in 2003. Rhett McNeil, who in 2011 translated The Splendor of Portugal, the haunting novel by António Lobo Antunes, produced the English versions of both Joseph Walser and Klaus Klump.

Tavares has been Portugal’s rising literary mestre since he was awarded the Saramago Prize at 35, nine years ago. American readers got their first taste of his startling prose and his obsessive interest in the dynamics of power—strength and weakness, mind and machinery — with Jerusalem, which Dalkey Archive published in 2007 in the English translation by Anna Kushner. That book was Tavares’s third in his four-part Kingdom cycle. Dalkey put out the last book in the series, Learning to Pray in the Age of Technique, in 2011 in the translation by Daniel Hahn, followed by the second, Joseph Walser’s Machine, in 2012, and now this month the first, A Man: Klaus Klump, which was published originally in Portugal in 2003. Rhett McNeil, who in 2011 translated The Splendor of Portugal, the haunting novel by António Lobo Antunes, produced the English versions of both Joseph Walser and Klaus Klump.

The four books are set in a fictional, somewhat Germanic-seeming city at the time of an invasion and occupation by a foreign army and they share characters and character types: powerful people — like industrialists and doctors — and distinctly fragile ones — invalids, mental patients, and quiet workers. The industrialist Leo Vast of Klaus Klump owns the factory where the reticent Joseph Walser works; Walser encounters the soldier Hinnerk Obst on a city street during the war. By the time of Jerusalem, Obst is suffering from PTSD and has an uncontrollable urge to kill (and after smelling his gun, devour human flesh). In each book, Tavares has given us a cold, amoral manipulator who, through reason and will, attempts to hack the laws of nature for profit, political gain, or professional advancement. One of them, Jerusalem’s Dr. Theodore Busbeck, is researching the correlation between human atrocity and history, in search of a groundbreaking “formula laying bare the cause of all the evil men do for no good reason.”

The Kingdom cycle itself reads as a kind of objective inquiry, as if Tavares, with language uncorrupted by sentiment and attachment, is in search of the secret order of mankind. “Animals know the law: strength, strength, strength,” he writes in Klaus Klump. “The weak ones fall and do what the strong ones want.” But the natural world can’t account for the effects of shame or humiliation. A sadistic teacher had practiced corporal punishment on the child Klump; Busbeck’s father Thomas had been willful and cruel to both Theodore and Theodore’s physically disabled son Kaas; and in Learning to Pray, protagonist Lenz Buchmann’s father Frederich is an old army commander who believes foremost in strength and domination. “In this house, fear is illegal,” he told Lenz and Lenz’s brother Albert. “I can hear of any accusation about you, you can commit the most immoral acts, you can have the police coming after you, or even the devil himself; I will defend my sons with any weapon I have. I will only be ashamed if I hear that you have been afraid. If that happens, don’t bother to come running here: you will find this door closed to you.”

What’s needed, for those who wish to assert power in Tavares’ books, is distance, from fear as well as love; distance allows for objectivity, a clear sense of one’s goals uncolored by emotion. Man can be as predictable and reliable as a machine, if only he can control himself and others around him.

Can Klaus Klump achieve this sort of distance? Not now — the invasion by a fictional foreign military has interrupted his climb and ill-timed desire has put him in the arms of Herthe, a prostitute, who has set him up. (In Tavares, rather disturbingly, most women are either prostitutes or mentally ill and whereas fathers dominate their sons, mothers are inconsequential.) Klaus is arrested and imprisoned. In jail, he befriends the monstrous Xalak, thinking, “I’m going to be your friend until I’m able to kill you.”

At 93 pages, A Man: Klaus Klump is the shortest of the four novels of the cycle. The prose is characteristically slender, naïve, as if rendered by an alien:

Klaus’s gums were very red. There was blood on Klaus’s lower gum. Vitamins are important for the sentences you speak. Klaus now spoke with faulty grammar, he spoke confusedly. He lacked vitamins in his gums and his sentences had lost their former precision. He no longer discoursed promptly and aptly. His sentences were approximations, attempts. Language deprived of vitamins is incompatible with reality.

The distance pricks the reader. The words rendered this way certainly taste different. But the detached form inherently eschews emotion; for all Klaus endures, the reader doesn’t feel much of anything for him. Once the war ended, “Klaus grabbed hold of the family business as he’d previously grabbed hold of weapons: calmly and coldly,” says Tavares, for that is the only reasonable way to go on.

In Klaus Klump, we’re seeing early experimentation with the form that will ripen as the cycle unfurls, so that eventually, in Jerusalem and Learning to Pray, Tavares is able to extract sensation from the brittle machinations of human behavior in order to deliver tragedy that feels like tragedy and melancholy that emerges from the genuine failure of will. In Jerusalem, Tavares’s characters explode with the raw vulnerability that Klaus and Leo Vast (and Joseph Walser) lack. Moreover, with the reckless figures Theodore Busbeck and Lenz Buchmann, Tavares demonstrates that even within the realm of detached language — this radical rational form — his characters can occupy real emotional space. In the complexity of their failures, they linger with us in ways the strangely bland Klump cannot.

It’s notable that the year before Rhett McNeil produced the excellent translations of Joseph Walser’s Machine, which was longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award, and Klaus Klump, he translated Lobo Antunes’s masterpiece The Splendor of Portugal, a Faulknerian opera of family disappointment and shame also published by Dalkey. The tone, structure, and psychological ambition of Antunes’s book is quite the opposite of Tavares’s work — a testament to McNeil’s extraordinary talent as a translator. But Antunes’s riveting, unsettling, utterly lyrical book, told in the distinctly sad overlapping voices of four members of a once wealthy family whose plantation was lost during the war for Angolan independence, suggests that Tavares’s approach in the Kingdom cycle is limiting. (Tavares interestingly was born in Angola in 1970, in the middle of the Angolan war.) Without a real city and its particular culture, history, and visceral reality — and without having invented these things for his fictional “Kingdom” — the worry is that he is left with abstract ideas of them: the idea of a political system, the idea of dark and dangerous streets, the idea of cruelty, the idea, even, of graffiti.

Tavares would say, I imagine, that the clinical distance is what gives his books their strange power. Through him, we’re able to taste the world — offered in exquisite, sampler-sized portions — as if we’ve never eaten before.