At the Union Square offices of Soho Press, news has circulated that one of their recent titles, Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See by Juliann Garey, has just been longlisted for The Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. Senior Publicity Director Meredith Barnes rushes to shoot emails to press, and Editor-in-Chief Bronwen Hruska delivers the news to the author. Everyone is proud; you can see it on the faces of the now many employees at Soho Press, but it wasn’t always this way. Today is a good day to talk to Bronwen Hruska about the Soho that once was, the Soho that almost wasn’t and the Soho that’s full of smiles today.

Since its inception, Soho Press has maintained its reputation as a reputable independent publishing house both in the realms of crime/mystery fiction and literary fiction. In recent years, readers have become acquainted with a new incarnation of Soho Press, one born out of loss, perseverance, and respect.

Soho Press launched in 1986, the brainchild of Laura Chapman Hruska, Alan Hruska, Juris Jurjevics, and his wife, Laurie Colwin. It was a serendipitous grouping of friends — all four had roots firmly planted in the publishing world in different ways. Jurjevics, at the time, was an established editor at Dial Press. Laurie Colwin was a novelist and contributor to The New Yorker and Playboy Magazine. Bronwen’s mother was a successful novelist who wrote under the name Laura Chapman, and her father, Alan Hruska, was a lawyer with a few successful forays into writing. One night over drinks (at a Soho bar, the only real connection between the press and the neighborhood), the group found themselves bemoaning the state of publishing. Chapman had seen success with several published novels at Doubleday, but she also had two historical fiction books for which she’d yet to find a home. The group consensus was that there was a serious plight of new and interesting fiction being overlooked. Between the four of them, they’d seen countless books deserving of a life that went unpublished. Soho Press was to be a solution to that problem.

Bronwen was already a sophomore in college when her parents started Soho. Although she always considered her parents “intimidatingly awesome,” working with them at Soho was never her goal. Bronwen had a successful career as a writer. She was a regular contributor to the LA Times and a staff writer for Entertainment Weekly, the experience of which is fictionalized in her debut novel, Accelerated.

Bronwen never wanted to take the helm at Soho Press. Who would blame her? She’d already done the hard work to establish an identity elsewhere. Indeed, there was a connection between that identity and the company that her parents built, but the idea of letting that company inform who she was made her anxious.

“It was always in the back of my head,” she says. “Should I do this? Should I not? I really didn’t want to do it. I was a writer. That’s what I was trained in. It’s what I was good at.”

She’d succeeded in a difficult industry and that solidified her identity as a writer. Publishing was a related but entirely separate world, a world in which Soho was becoming a recognized name.

The Inception

Soho Press had an office in Union Square with a small staff and a strong set of standards and values for doing business. It was considered a constant at Soho that they would always accept unsolicited manuscripts. Not to consider unsolicited manuscripts would go against their original ethos — to create a home for writers who’d been ignored or outcast by mainstream publishing. Another pillar of the Soho mission statement was to make sure that the books they published could be found by potential readers. From the beginning, they worked to make sure they had distribution that surpassed the limited reach of your average independent house, at first by handing it to FSG, until the publisher decided to stop handling client publishers. They then moved their distribution to Consortium. Bronwen feels that in part it was their list and the reputation of the team that helped them to be taken seriously as clients, rather than just some fledgling indie.

Too often, independent is associated with undiscerning, and Soho was determined to prove otherwise. Their standards were high, and their vetting was rigorous albeit not exclusive. According to Bronwen, Soho has always considered slush because it leads to at least one to two Soho literary titles per year.

“It’s a hard time to find an agent,” she says. “It’s a hard time to find a publisher even if you have an agent! So I know there are very talented writers out there who have great novels that deserve to be read by editors.”

However, how the press views slush has evolved. Bronwen stipulates that it’s rigorous, particularly because Soho only publishes 10 to 12 literary titles per year, and for the past couple years, they’ve had to stop considering unsolicited crime manuscripts.

The process first paid off with the discovery of a manuscript entitled Breath, Eyes, Memory by a Haitian-born author named Edwidge Danticat. The novel, a story of a young girl moving from Haiti to New York City, set the tone for Soho’s literary imprint, which would go on to publish many successful novels that dealt with culture clash. Soho would also succeed with early books by celebrities like Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry. “There was a lot of discovering authors who would go on to have really big careers,” Bronwen says. Put simply, Soho represented the voices of authors who’d otherwise been ignored while maintaining a high standard. It was a refusal to believe that major houses had snatched up all the high-caliber fiction out there.

The process first paid off with the discovery of a manuscript entitled Breath, Eyes, Memory by a Haitian-born author named Edwidge Danticat. The novel, a story of a young girl moving from Haiti to New York City, set the tone for Soho’s literary imprint, which would go on to publish many successful novels that dealt with culture clash. Soho would also succeed with early books by celebrities like Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry. “There was a lot of discovering authors who would go on to have really big careers,” Bronwen says. Put simply, Soho represented the voices of authors who’d otherwise been ignored while maintaining a high standard. It was a refusal to believe that major houses had snatched up all the high-caliber fiction out there.

The catalogues of independent publishing houses also tend to reflect the tastes of the individual editors. Laura and Alan Hruska always had a special interest in books that focused on foreign cultures. Laura also had an enduring love of mystery and crime fiction. The Soho Crime imprint was launched in 1991 and took off so quickly that it almost usurped the identity of the Soho literary imprint. “Crime readers are rabid in the best possible way,” Bronwen says. It wasn’t something the press resented. Crime is what gave Soho the means to release and distribute all its literary titles, and it was one of Laura’s passions. At the same time, the company didn’t want to be known exclusively for the crime genre.

The Decision

Laura Hruska was diagnosed with cancer in 2003. For the first time, Bronwen considered joining the team, but only until her mother’s health improved. She came into the office here and there and helped out where she could, but her heart wasn’t in it. She struggled to find a place.

“One day I screwed up really bad,” she says.

Bronwen describes a galley she was working on. She forgot some small detail, like pressing “save.” As result, a bunch of galleys went out without copyediting changes. She felt terrible, guilty, and eventually she quit. Around that time, her mother went into remission. Bronwen went on to sell her first screenplay and begin a novel, and Soho continued to succeed as it had.

In 2006, Bronwen’s mother had a reoccurrence of breast cancer. She finally decided to ask Bronwen to consider coming to work for Soho with an eye for taking it over.

Bronwen knew she didn’t want to accept unless she really meant it. She’d learned from her time at Soho that publishing is hard — especially for anyone who didn’t really feel compelled to do it. She also learned that she knew almost nothing about the publishing industry.

On other hand, Bronwen had found herself a little bit closer to the position her mother was in when she started Soho Press. She was nearly finished with her first novel after working on it for over a year in a small weekly writing workshop. She was surrounded by aspiring novelists there and saw the kind of sweat and pain that can go into writing a novel. She witnessed how a promising new voice could blossom when given a little encouragement but also understood the tragedy of a good novel unpublished.

“I’d been a writer for my entire career up to that point,” she says. “There were a lot of good — really good — books out there and fewer and fewer opportunities for those books to be published. I’ll admit the romantic ideal of being able to help great books have a life — the mandate that gave birth to Soho in the first place — was very appealing to me.”

At lunch with a close friend, Bronwen discussed the truly life-altering decision at hand. She was still unsure. Her friend’s response was unequivocal.

“She said to me, ‘Are you crazy? Your dying mother asks you to take over her publishing company — you say yes!’”

But it wasn’t that easy. She pauses, and her facial expression tightens as she explains that she knew she couldn’t take over Soho unless she was certain it was what she wanted to do. If she wasn’t, her mother would know and wouldn’t allow her to say “yes.” Bronwen laughs, but the weight of her statement lingers. It’s the idea of a parent not allowing her child to do what she herself most wants unless she’s certain it will make her child happy. It’s something one who isn’t a parent probably cannot truly understand. Bronwen adds that up to that point she truly didn’t believe that she was going to accept the offer.

“Then, I decided that I needed to at least give it a serious chance,” she says.

With that decision, Bronwen went from being a grown woman and professional writer who made her own schedule to working nine to five in a small office side by side with her mother.

“I felt like I was 21.”

The Transition

At the time, only five people worked in the Soho Press office, which consisted of one wide-open room. Bronwen quickly found that her past frustrations with the job came from not understanding the logistics of the industry. The more that changed, the more her opinion of the job changed. As time passed, Bronwen became serious about becoming editor-in-chief of Soho Press.

Bronwen’s mother died in 2010. By then, Bronwen had grown to love the job, the publishing world, and Soho Press more than she ever thought she could. Bronwen took the reins at Soho and hoped to bring something new to the table. That was before she realized that keeping the business intact would become the first priority.

Unfortunately, there was a potentially ruinous obstacle at bay — the publishing industry was falling apart. Major book retailers were closing their doors. Second-hand markets and Amazon were eating up a large chunk of publishers’ and retailers’ profits. And people still weren’t sure if there was a future in ebooks.

“I couldn’t believe how bad it was,” Bronwen says. “I wondered how we could possibly even have a business; it was dismal.”

Bronwen credits the company’s survival in part to e-books and to Soho’s head of marketing at the time taking the burgeoning medium seriously when many throughout the industry did not. Soho made a concerted effort to publish and advertise the electronic versions of their titles during a time when most publishing houses weren’t. They also tightened their belts. Bronwen and her mother, when she was there, forwent their salaries until things turned around. With only five employees at the time, that meant only three of them were being paid.

Aside from keeping Soho Press alive, Bronwen’s goal as editor-in-chief was, in part, to breathe new life into the literary fiction division. Crime had been so successful since its launch that it overshadowed the rest of the company. When people thought about the house, Soho Crime was the first thing that came to mind, thanks in part to collections like Massie Dobbs — a series about an English housemaid turned private investigator. The downturn in the publishing industry made things a bit more complicated. Now ramping up both imprints was integral for the company’s survival.

The Transformation

Author Alex Shakar wrote the book that represented a new era for Soho’s literary imprint. The story of Shakar’s pre-Soho career has become something of a cautionary tale in the literary world. Shakar’s second novel, Luminarium, not only meant a new chapter for Soho, but a happy ending for Shakar as well.

Author Alex Shakar wrote the book that represented a new era for Soho’s literary imprint. The story of Shakar’s pre-Soho career has become something of a cautionary tale in the literary world. Shakar’s second novel, Luminarium, not only meant a new chapter for Soho, but a happy ending for Shakar as well.

When Shakar’s first book was picked up for publication, it had all the indicators of success: a hotshot agent, big name blurbs, and a large advance from HarperCollins. The novel entitled The Savage Girl was a satire of consumer culture with subversive elements, all of which would generally make for a promising first outing — if not for a pub date exactly one week after 9/11. Shakar found himself abandoned. His agent, Bill Clegg, was forced to take time off, a story recounted in Clegg’s memoir Portrait of the Addict As a Young Man, and The Savage Girl flopped. Of all the writers who had it rough during the publishing downturn, writers with a so-called “bad track record” may have had the worst. Shakar recounted the experience in his essay, “Year of Wonders.”

Clegg had just come off a long convalescence period when he had lunch with original Soho co-founder Juri Jujrevics. It was Jurjevics who helped convince Clegg to return, as it was his firm belief that Clegg was one of the brightest and promising agents in the business. As a result, Clegg had a soft spot for Jurjevics and Soho.

Shakar took his time writing his follow-up to The Savage Girl and stuck with Clegg as his agent. However, the Murphy’s Law chain of events surrounding The Savage Girl left Shakar in a tough spot. Fate and proximity put Shakar, Clegg, and Bronwen together at book party in Bronwen’s apartment where the three discussed the book.

“I had the good fortune of coming to Soho at an exciting time,” Shakar says. “The place was bubbling with energy and ambition. Having just stopped by couple weeks ago, I’m happy to say that it still is.”

Luminarium wasn’t just a compelling read — it was a novel that made a statement. It sojourned into realms of fractured reality and of spirituality. It was heady and fresh yet unique. It was exactly the kind of book Soho’s new literary editor Mark Doten had been looking for to set the tone for the future.

Doten had gotten his MFA at Columbia and worked under the likes of Ben Marcus and Sam Lipsyte. According to a 2007 feature in New York Magazine, Doten had distinguished himself as a rising star in the hyper-competitive program. Doten’s debut novel is set to publish in February 2015 by Graywolf, a publisher whom Bronwen admittedly considers friendly competition. The interplay between Bronwen and Doten seems to account for what’s become the strongly realized identity of the new Soho Press. For Bronwen, the driving factor that moves her to want to publish a book is a plot that keeps a reader turning the pages — a big part of what made her own 2013 novel Accelerated a success. Doten, on the other hand, is more focused on the importance of voice.

“I’m looking for a novel that couldn’t have possibly been told by anyone other than that particular storyteller,” he says.

The Restoration

The melding of those priorities is reflected throughout the notable books of Soho’s post-2011 literary catalogue. A few people interviewed for this piece referred to a “Soho feel” or “a quintessential Soho book.” Trying to piece to together what that meant wasn’t easy. It’s not something you’d find in the content or even the style. It would be wrong to use words like “dark” or “edgy,” though those qualities are often present.

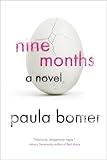

Take Paula Bomer’s Soho debut. Nine Months is a dark and honest take on pregnancy that embraces the goriest of details while maintaining the emotional breadth of such a sacred life event. Bomer refers to her experience working with the team at Soho as both “fun” and “life changing.” Her follow-up, Inside Madeline, published this month.

Take Paula Bomer’s Soho debut. Nine Months is a dark and honest take on pregnancy that embraces the goriest of details while maintaining the emotional breadth of such a sacred life event. Bomer refers to her experience working with the team at Soho as both “fun” and “life changing.” Her follow-up, Inside Madeline, published this month.

“I think what Soho does is unique in that there really is a family feel. It’s always been a joy for me to do business with everyone, from the publishers to the assistants,” says Bomer, who dedicated her first novel to Doten. During these interviews, multiple authors echo the notion that the process of editing with Doten is responsible for elevating their manuscripts.

Matt Bell’s In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and The Woods is a recent Soho title that both Doten and Bronwen consider especially important to their timeline. The book was well reviewed in The New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, and more, and made The Believer’s top 20 list for fiction. The novel, on its surface, is about a couple who move into a secluded house and have trouble conceiving, but ask someone who’s read the book, and they’re most likely to talk about the giant squids or sentient bear or huge labyrinth underneath the house. As Doten puts it, “It’s a book where the way in which the physical world is presented is heavily influenced by the character’s psychology.” Both Bronwen and Doten consider Bell’s novel “a quintessential Soho Press book.” It’s hard to say what Breath, Eyes, Memory, Lumiarium, and In the House have in common — but the same can be said for recently successful indies like Akashic or Two Dollar Radio; the qualities they look for are more or less intangible.

Matt Bell’s In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and The Woods is a recent Soho title that both Doten and Bronwen consider especially important to their timeline. The book was well reviewed in The New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, and more, and made The Believer’s top 20 list for fiction. The novel, on its surface, is about a couple who move into a secluded house and have trouble conceiving, but ask someone who’s read the book, and they’re most likely to talk about the giant squids or sentient bear or huge labyrinth underneath the house. As Doten puts it, “It’s a book where the way in which the physical world is presented is heavily influenced by the character’s psychology.” Both Bronwen and Doten consider Bell’s novel “a quintessential Soho Press book.” It’s hard to say what Breath, Eyes, Memory, Lumiarium, and In the House have in common — but the same can be said for recently successful indies like Akashic or Two Dollar Radio; the qualities they look for are more or less intangible.

The Legacy

Fortunately for Bronwen, the publishing industry didn’t fall apart completely and neither did Soho Press. In fact, both Doten and Bronwen echo the sentiment that they’ve seen nothing but growth since coming on board. One of Bronwen’s biggest contributions to Soho is a heightened focus on the importance of marketing. What was once a one-person department now consists of five employees. What was once a company consisting of five employees is now 16. Soho has also recently handed their distribution over to Random House, making their titles especially accessible throughout the country. In doing so, Bronwen and company have realized the dream of their predecessors — to build an indie house with the same reach as the majors. Aside from Doten’s eye for quality work and keen editorial skills, Bronwen credits him for his knowledge of the literary community and for his ability to move confidently throughout it. Doten admits that though it was something he once lamented about the job, he’s gotten good at “going out and drinking with people.”

When she first joined Soho Press, Bronwen’s reservations concerned identity, losing her own, or somehow marring the one that her mother had built. Certainly the latter isn’t a concern. The Soho Crime division is as vibrant as ever, with crime editor Juliet Grames keeping the international flavor favored by the crime division of days past — only now it also focuses on locales that are exotic in different ways. Recent Soho Crime releases include titles taking place in Mormon Utah or the Alaskan wilderness. Crime fans still know what to expect from the imprint. As for the literary division, Soho is as true to the hopes and aspirations of the four people in that downtown bar as they’ve ever been.

“They’re smart and they’re plugged in, and you can really feel when you walk in there that they love what they do,” Shakar says.

The prospect of letting a parent down is scary, perhaps as much for a four year old as it is for a forty year old. Once a parent has passed on, that prospect becomes something entirely different, something far beyond appeasement or resentment. For Bronwen, joining Soho has become a way to keep her mother closer than she ever thought she could. A book will come up that she remembers her mother reading or acquiring. She’ll stumble across books or a note with her mother’s handwriting. She’s surrounded by hundreds of thousands of pages of her mother’s work and passion. She didn’t just keep Soho Press afloat. By giving a voice to all those authors who wouldn’t have had one otherwise, she kept her mother’s voice spirit alive. The new Soho Press isn’t just a crime fiction or YA or even a literary fiction house, it’s a respected publishing house. It’s a home for writers who might not have had one otherwise.

Photos courtesy of Soho Press.